This interview is one of four in a series on this year’s finalists for New-York Historical's Children’s History Book Prize. Join us here as we talk to the authors to learn more about their amazing books. Our jury of teachers, librarians, historians, and middle-grade readers will help us select the winner, who will receive a $10,000 prize. We hope this prize elevates the winner and encourages authors and publishers to continue to create challenging, engaging, and well-researched history books for kids!

Today, we’re chatting with author Ami Polonsky about her book World Made of Glass. It’s 1987, and Iris is grappling with her father's AIDS diagnosis, her re-made family, and people at school's reactions. Polonsky's novel shows readers a girl focusing her rage and pain into action and love.

DiMenna Children's History Museum (DCHM): What made you want to tell a story set in the 1980s? Do you ever find that people resist talking about the 1980s as a period of history?

Ami Polonsky (AM): I didn’t set out to tell a story set in the '80s so much as I set out to tell this particular story about the early days of HIV and AIDS which, of course, plopped World Made of Glass into the spring of 1987. Iris and I are just about the same age; I was also in middle school in the spring of 1987, so in the sense of understanding how it feels to be a child of a certain demographic at that time, the story felt natural to write. As an aside, I’ll admit that thinking of my childhood as historical fiction doesn’t sit well with me. Am I really that old?! It takes a minute to realize that yes, the 1980s are indeed historical at this point! Including elements of fashion and pop culture from the '80s was fun, but I tried not to overdo it because I could have spent ages in that rabbit hole. It was really sad to delve into the societal and medical ramifications of Reagan’s presidency on the LGBTQ+ community. As a kid who grew up during that era in a liberal home, I knew that my family didn’t approve of the government, but I didn’t realize the extent of the damage that his administration did on the LGBTQ+ community until I revisited the time period as an adult.

DCHM: Throughout your book, Iris and her dad trade poems back and forth. What inspired the idea for them to connect in that way? Why did you choose acrostic poems, a style in which the first letter of each line spells out a word, name, or phrase when read vertically?

AM: Writing the acrostic poetry was so much fun for me; it was probably my favorite part of writing this book. In addition to writing for middle schoolers, I work as an English department chair in a middle school. Prior to my current position, I taught middle school English on and off starting in 2000. All this to say, I’m a real English nerd at heart. I’ll admit that my love for acrostic poetry began as a joke with a colleague who is also a close friend. We were talking about authentic writing experiences we could engage our students in, and our conversation quickly devolved into a funny (to English nerds, at least!) list of ridiculous ways of communicating. Acrostic poetry was at the top of that list. I mean, you have to admit that on its surface (and in its modern form, as Iris and her dad clarify!) acrostic poetry is completely absurd. My interaction with my friend devolved further, and we began communicating in acrostic poetry. Amazingly, I found that I loved the format because there was something about having that first letter already in place that seemed to open doors to more creativity in writing. It seemed like such a random and endearing way for two people to communicate.

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. "Silence = Death Project. Silence = Death"The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1986.

DCHM: In your story, we see that the early years of the AIDS crisis were full of misinformation and fear. What is one thing about AIDS or the AIDS crisis that you want readers to know when they finish your book?

AM: It didn’t have to happen the way it happened. I think that, through reading World Made of Glass, readers will see that marginalized communities didn’t have to suffer with HIV and AIDS the way that they did. As Iris comes to learn in World Made of Glass, her dad died because he was gay. If HIV and AIDS were impacting non-marginalized people, the government and drug companies would have acted much more efficiently. It wouldn’t have taken years and years of self-advocacy for drugs to be tested and ultimately become available because the people with power would have cared more. So, I want readers to understand that biases impact marginalized people in all kinds of ways. I think many children can understand how othering someone can make that person feel excluded, but it takes some conversation to show young readers the full gamut of negative impacts that marginalization can have. And, of course, I want young readers to see that there were many, many opportunities for things to unfold differently so that, moving forward, they can help bring our world to a better place where everyone gets the respect and care they deserve.

DCHM: Were there any particular sources you looked at for research while writing this book?

AM: The most valuable resource for me was the Act Up Oral History Project. Tim Hubbard and Sarah Schulman interviewed nearly 200 still-living members of Act Up New York and compiled the interviews. This was a gift to humanity in so many ways. I can’t stress enough how important it is, when writing historical fiction, to get as close to the original sources as possible. The Act Up Oral History Project allowed me to hear the exact words spoken by the people who were there, and I wouldn’t have been able to write a historically accurate account of the time period without it.

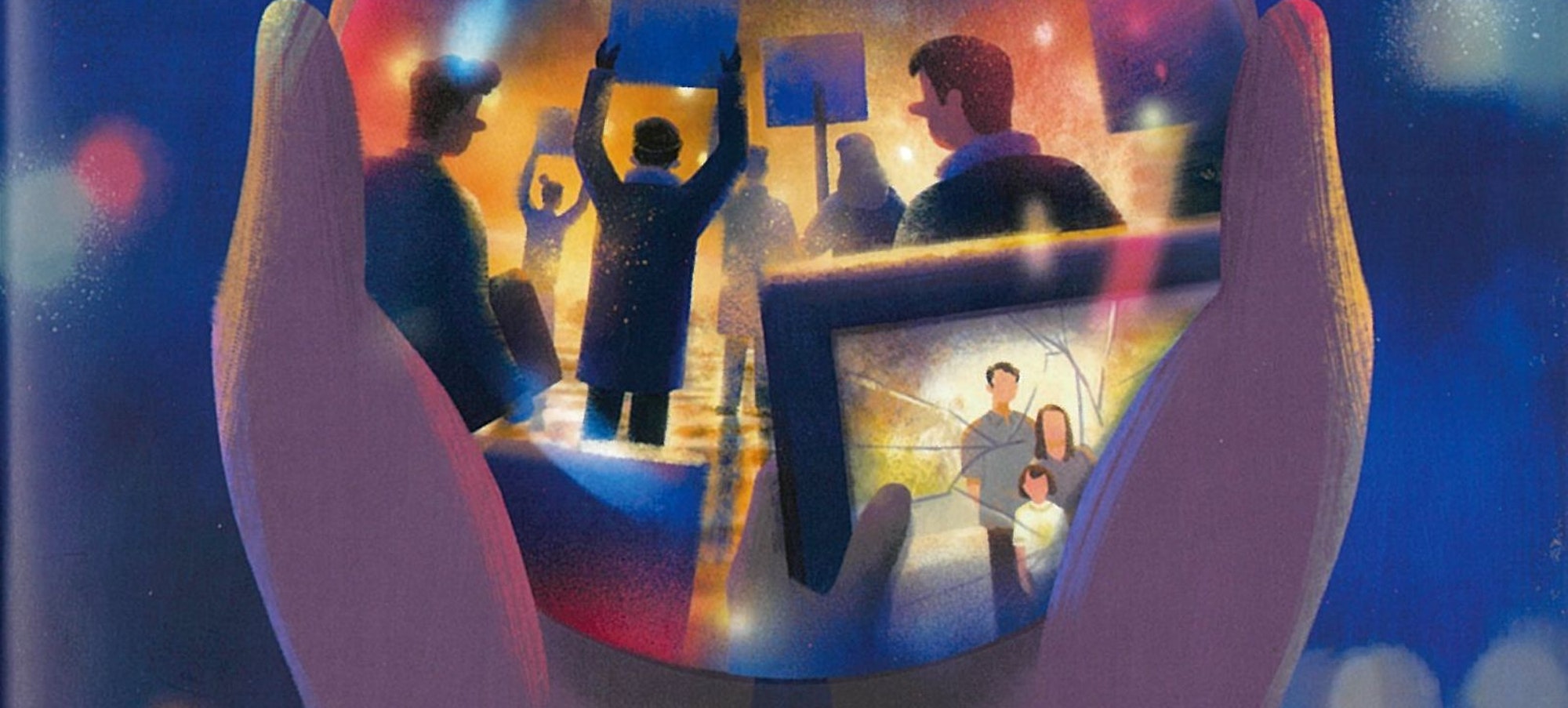

ACT UP protest in Manhattan, circa 1990, MACMILLAN

DCHM: What three words would you use to describe World Made of Glass?

AM: Sad, optimistic, and hopeful.

Thank you Ami!

Ami Polonsky is a middle school English teacher, parent to two children, and author, among other things. Her critically acclaimed novels for young readers include Gracefully Grayson, Threads, and Spin with Me. Ami lives outside of Chicago with her family. She invites you to visit her online at amipolonsky.com.