This interview is one of four in a series on this year’s finalists for New-York Historical's Children’s History Book Prize. Make sure to read them all and learn more about the amazing books and authors! Our jury of teachers, librarians, historians, and middle-grade readers help us select the winner, who will receive a $10,000 prize. We hope this prize helps to elevate the winning book and encourages authors and publishers to continue to create challenging, engaging, and well-researched history books for kids!

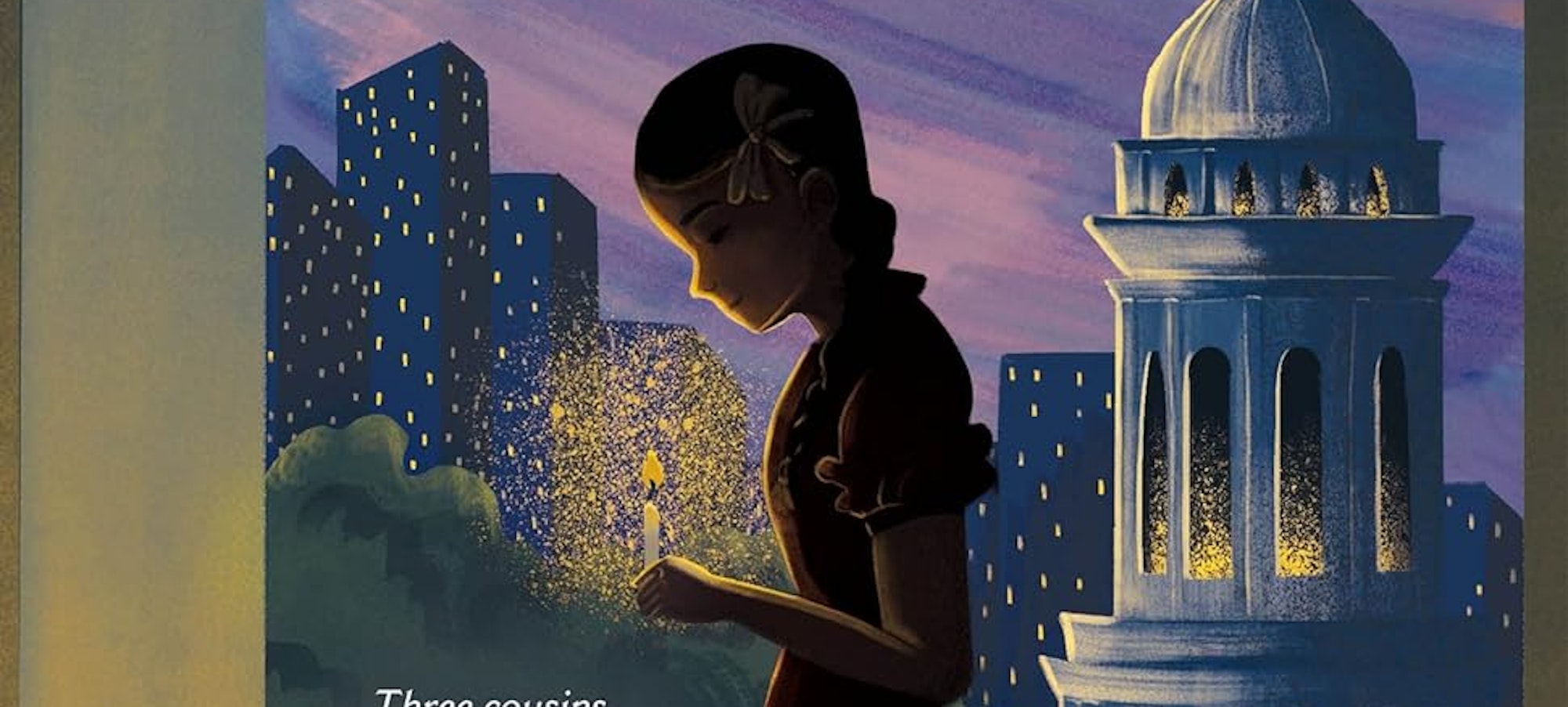

Today, we’re chatting with author Katherine Marsh about her book The Lost Year.

DiMenna Children's History Museum (DCHM): Your book begins with a boy living through the COVID-19 pandemic. Why did you choose to start in the present and then time jump to the 1930s?

Katherine Marsh (KM): Initially, I started my book set in the 1930s. But I was worried that kids would find a story set over 90 years ago and partly in a foreign country to be emotionally remote. Then the COVID pandemic happened. I was stuck home with my own children, including a middle schooler, as we lived through a deeply disruptive, divisive, and frightening period of history that felt unprecedented. I’m a journalist by training and was compelled to record the experience. The anxiety that my character Matthew feels, that we all felt, especially in those early days of the pandemic also struck me as a way to help young readers understand the grief, fear and uncertainty of another dark period of history, namely Holodomor and Stalin’s reign. Finally, I loved the idea of a kid today having to solve a historical mystery, one that could only be solved by forging human connection, specifically with different generations of his own family.

DCHM: Did you know about the Holodomor before you wrote this book? Were you surprised by any of the history you learned while writing?

KM: I grew up in the home of my Ukrainian grandma in Yonkers, NY. She corresponded with her sisters and their families in Ukraine for nearly 70 years after immigrating to America at the age of 21. In 1933, a year after my mother was born, she took in her cousin’s daughter who was able to immigrate after experiencing the famine firsthand. My grandma also ran a bar with my Belarusian grandfather on East 10th Street that served immigrants from all over Eastern Europe, including from Ukraine. We knew about Holodomor from all these sources.

The history I learned as I researched that I hadn’t been aware of and that absolutely appalled me was how Stalin actively restricted movement during the height of the famine by creating a system of internal passports. In other words, he deliberately prevented starving Ukrainians, including children, from leaving, thus knowingly ensuring their deaths from hunger.

DCHM: The subject of your book can be pretty sad and hard to talk about. Why did you decide that this was an important story to tell? Was there a strategy you used to make this story work for a middle grade audience?

KM: Growing up, I felt frustrated that so many Americans had never heard of Holodomor, in large part because of Stalin’s campaign of disinformation, which affected Western coverage as well. We often think of disinformation as a 21st-century phenomenon, but, as a journalist, I felt it was important for young people to understand that disinformation has a long and destructive history. If you want them to be critical readers and practice media literacy today, you need to make the historical and emotional stakes of disinformation clear. Holodomor is a case study in how Stalin’s use of propaganda and censorship covered up his crimes, silenced his victims, and warped people’s understanding of history for decades.

As to your second question, a lot of young people feel anxiety these days—it’s been heightened since the pandemic, although I don’t think that’s the sole cause. Turning away from dark material or difficult moments of history does not do young people a service, however. Reminding them that they can face difficult times and uncomfortable emotions and survive them is a better recipe for resilience. Assuring them that they can change and evolve even in the wake of a mistake is a better recipe for growth. Stories are a powerful way to remind young people that they’re not alone in feeling as they do and that they can make connections not only with others alive today but across time. This is all a long way of saying that I always counterbalance a sad or difficult story for young people with hope and redemption.

DCHM: Were there any particular sources you looked at for research while writing this book?

KM: I relied on a number of different primary and secondary sources: histories of Holodomor and Stalin’s reign; the 1980s Congressional testimony from Holodomor victims; survivor accounts from Canada and the United States. I used various contemporaneous newspaper accounts (including the battling reports of Gareth Jones and Walter Duranty). I consulted with historians who specialize in Soviet History and had three of them read my drafts for accuracy. I interviewed several 90- to 100-year-old women with childhood memories of 1930s Brooklyn where part of my story takes place. I interviewed my own family members in Ukraine and in the United States who are the descendants of Holodomor survivors. I’m particularly proud of a short documentary about our family story that I made with my cousin, Andrea Zoltanetzky, who grew up in Brooklyn and is now a professional food photographer in Berlin.

DCHM: What three words would you use to describe The Lost Year?

KM: Mystery. History. Twist.

Thank you Katherine!

Katherine Marsh is an award-winning author of novels for middle-grade readers including The Lost Year; Nowhere Boy; The Night Tourist; Medusa: The Myth of Monsters and more. Among her honors are National Book Award finalist, winner of the Edgar Award for Best Juvenile Mystery, winner of the Jane Addams Award for Children's Chapter Books, and winner of the Middle East Book Award. A former magazine journalist, Katherine lives in Washington, DC with her husband, two children and an astonishing array of pets.