Fred McDarrah, photographer. Untitled (New England Gay Pride at the Sixth Annual Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day), New York, New York, June 29, 1975. Gift of the Goldman Sonnenfeldt Family, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

“The shouting has died. The slogans are passé,” wrote Village Voice reporter Arthur Bell, describing the 1975 Pride March in his popular “Bell Tells” column. “It’s no longer ‘gay is good’ or ‘gay power,’ but ‘gay is here, let’s ball.’”

“As one who has been walking the route since 1970, I found the day still glorious,” Bell continued. “Sideline gawkers joined the marchers to the tune of ‘Out of the closet and into the streets.’ By the time the parade entered Central Park, the closets were empty. Overall, the day was closer to the first march of 1970. It was less professional, more spontaneous, as if we didn’t have to do it to prove a point. We wanted to do it, and that was the point.”

Rather more prosaically, Village Voice photographer Fred McDarrah scribbled in his daybook for June 29, 1975, “A chilly day indeed to gay lib march from 10 AM till 2 PM took 10 rolls & the stuff looks fine…”

Marquette, maker. Daybook belonging to Fred McDarrah, 1975. Gift of the Goldman Sonnenfeldt Family, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

With so many images to choose from, it’s no wonder that the 1975 march is well-represented in our current exhibition, Fred McDarrah: Pride and Protest, originally curated by Vince Aletti. The items on display are among the archival materials and artifacts in the Fred W. McDarrah Archive, recently acquired by The New York Historical through the generosity of MUUS Collection. The archive consists of 51,100 photos, 225,000 negatives, 9,000 contact sheets, correspondence, ephemera, photographic equipment, and daybooks/journals covering McDarrah's personal and professional activities from 1948 to 2007.

To celebrate the arrival of this historic collection in our Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, we are excited to share some of the stories behind McDarrah’s iconic photos of the 1975 Pride March in honor of its fiftieth anniversary. While Bell’s written account gives a grand overview of the day, in McDarrah’s photographs we can see the expressions of joy, affection, and pride on individual faces.

Fred McDarrah, photographer. Vito Russo at the Gay Pride March, New York, New York, June 29, 1975. Gift of the Goldman Sonnenfeldt Family, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

Vito Russo (1946–1990), photographed in Sheridan Square, was a film scholar, a journalist, and a passionate advocate for gay rights. Born into a close-knit Italian American family and raised in East Harlem, Russo was in many ways a quintessential New Yorker—but above all, as his brother Charles Russo remembered, “Vito was a teacher.” In the mid-1970s, Russo developed a series of informative lectures on Hollywood homophobia, which he refined and expanded over the course of many years, presenting at over 200 venues—universities, film festivals, community centers, and museums—throughout the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia. These lectures evolved into his landmark exposé, The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies, which was published in 1981, revised in 1987, and became the basis of an award-winning 1995 documentary film. Russo, wrote biographer Michael Schiavi, “taught gay readers that the bigotry they suffered offscreen correlated directly to the lies perpetuated about them onscreen.”

Russo began sharing his knowledge and love of film with others in the mid-1960s, via the Film Arts Club that he hosted as an undergraduate at Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey. But by June 1969, he was back in New York City, where he witnessed the first night of the Stonewall uprising, watching as patrons of the Mafia-owned bar fought back during a routine police raid. Galvanized, Russo returned as a participant during the subsequent nights of unrest. In 1970, he joined the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) as the organization protested another violent police raid, this time on the Snake Pit bar. By June 1970—the first anniversary of Stonewall—Russo was helping carry the GAA banner during the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, forerunner of Pride. (Columnist Arthur Bell, one of GAA’s founders, became a friend of Russo’s, and the two participated in several of GAA's high-profile “zaps.”) Russo also served as chair of the GAA Arts Committee, arguing that “you don't change people by changing laws… the way you reach people was through media.” One of his most popular initiatives was the “Firehouse Flicks,” a series of film screenings at the GAA Firehouse, that sparked discussions about “machismo, sexism, gender role-playing, romance, violence, and the denigration of gays and lesbians in Hollywood.”

In 1971, Russo earned his MA in cinema from New York University and began working at the Museum of Modern Art film library. Russo held the job at MoMA for two years, but for most of his career he supported himself as a freelance writer. In this 1975 photo, McDarrah captured Russo wearing an Advocate t-shirt, advertising the nationally distributed gay publication for which he had just interviewed Bette Midler. Later, Russo would contribute more profiles and reviews of New York City nightlife and entertainment, not only to gay publications like the Advocate and the New York Native, but to mainstream magazines and newspapers such as the Village Voice, Rolling Stone, and Esquire.

Diagnosed with HIV in 1985, Russo cofounded Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (now GLAAD) to combat media misinformation about HIV/AIDS. His legendary charisma helped bring people into the nascent organization, as author and activist Jewelle Gomez, who would later become the group's first treasurer, recalled in a 2024 interview:

I bumped into Vito Russo on the street during this period, and Vito said, “So, Jewelle, aren’t you coming to our meeting?” and I was like, “Oh! I don't know,” [laughs]. I felt like I was just stretched too thin. He said, “Jewelle,” and I said, “Yeah, yeah, you’re right, ok, I’ll be there.”

Russo also co-founded the HIV/AIDS advocacy group ACT UP and hosted its Media Committee meetings at his Chelsea apartment. Despite the onset of AIDS-related complications, the last years of Russo’s life were full of activity. Twice in 1988, once during a protest in Albany and again at ACT UP's protest in front of the Health and Human Services building in Washington DC, he delivered powerful speeches now remembered as Why We Fight. He taught film classes in California, and appeared in the 1989 documentary Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt, where he discussed the death of his partner Jeff Sevcik and the panel he made in Sevcik’s honor for the NAMES Project Memorial Quilt. Russo's legacy is honored today with the Vito Russo Award, given annually by GLAAD to a LGBTQ+ media professional whose work accelerates LGBTQ+ awareness.

Fred McDarrah, photographer. Contact sheet, June 29, 1975. Gift of the Goldman Sonnenfeldt Family, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

You can see McDarrah’s photo of Russo circled in orange on the top row of one of his contact sheets from June 29, 1975. The same contact sheet also gives us more information about another photo on display in the gallery: the word “GAY” printed on translucent material, with marchers visible in the background.

Fred McDarrah, photographer. Untitled (Sixth Annual Christopher Street Liberation Day), New York, New York, June 29, 1975. Gift of the Goldman Sonnenfeldt Family, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

McDarrah’s contact sheet shows that the photographer, who rarely cropped his work, took a close-up on the “GAY DEMOCRATS” banner. This was most likely carried by members of Gay and Lesbian Independent Democrats, a political organization founded in 1974 by Jim Owles (1946–1993) and Allen Roskoff. Owles, a founding member of the Gay Activists Alliance and one of the first openly gay people to run for public office in New York City, would later co-found GLAAD alongside Vito Russo.

(Also visible in the same contact sheet? Three images of a luminous Marsha P. Johnson.)

Fred McDarrah, photographer. Contact sheet, June 29, 1975 (detail)

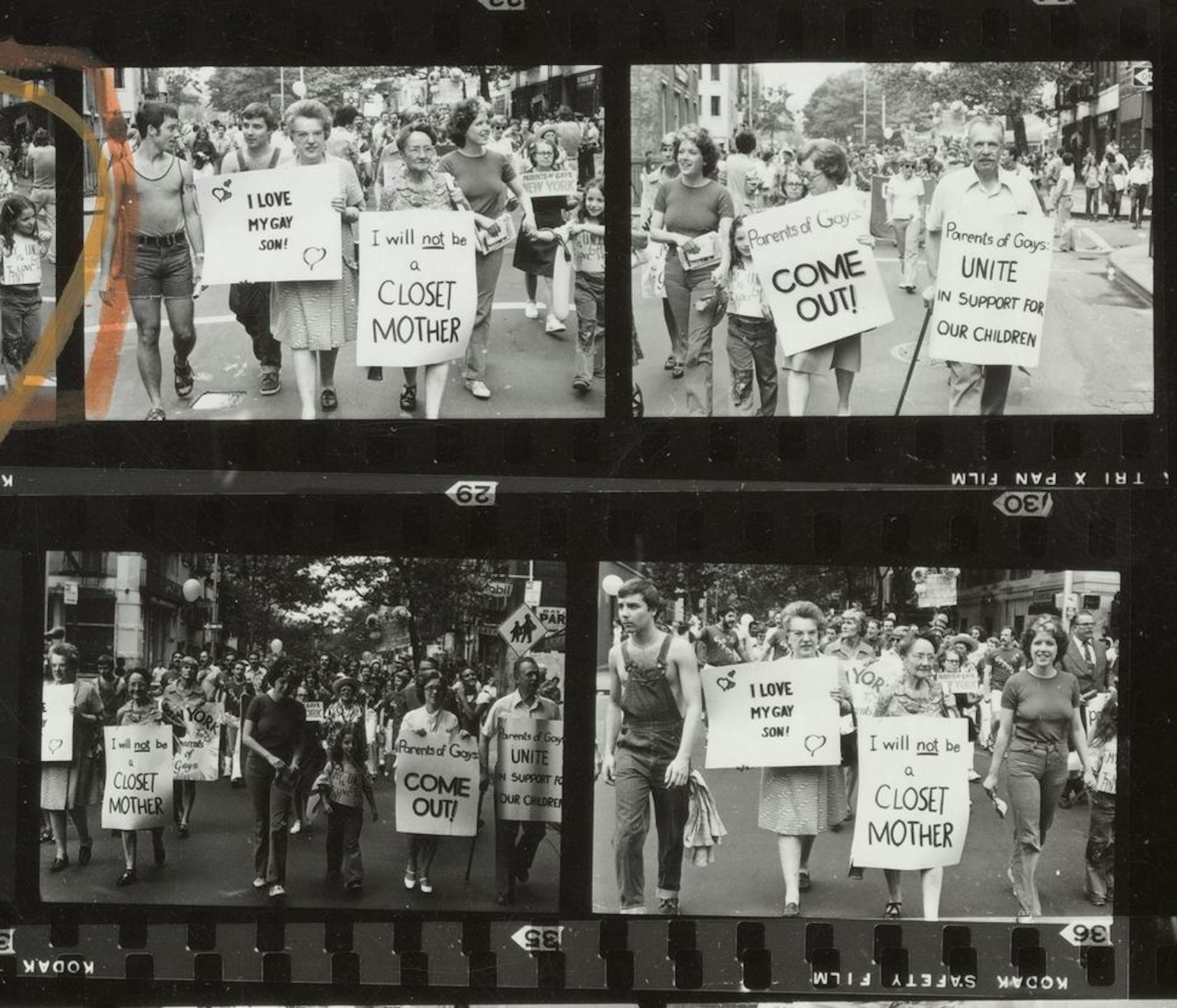

Fred McDarrah, photographer. Untitled (PFLAG members at the Sixth Annual Gay Liberation Day March), New York, New York, June 29, 1975. Gift of the Goldman Sonnenfeldt Family, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

McDarrah also photographed a number of supportive parents and family members, following in the footsteps of Jeanne Manford (1920–2013). After her son Morty was assaulted in 1972 while leafleting at a GAA protest, his mother Jeanne carried a sign at the 1972 Christopher Street Liberation Day March urging parents to support their gay children. “As we walked along, the people on the sidewalk screamed, they yelled, they ran over and kissed me,” Jeanne Manford later recalled.

The following year, Morty, Jeanne, and her husband Jules founded Parents of Gays (POG, now PFLAG). They were joined by Sarah Montgomery, aged 74, whose lifelong commitment to activism began when she marched for civil rights in the 1920s. She joined POG after losing her son and his partner to suicide in 1972. Her sign reads, “I will not be a CLOSET MOTHER.” McDarrah's photo also shows long-term POG member Willy Jump (wearing a striped shirt) marching behind Montgomery, and Morty’s sister, Suzanne Swan, is at the right of the image holding hands with her daughter Avril. Another of McDarrah’s contact sheets reveals that Jeanne and Jules Manford were also present, marching alongside their daughter and granddaughter.

Fred McDarrah, photographer. Contact sheet, June 29, 1975 (detail)

In a 2024 interview, Avril Swan reflected upon the lasting influence of her family's multigenerational activism:

My uncle was someone with strong opinions… He’d explain to me why he had the opinions that he had, and politically what was going on in the world—he was a teacher in my life. I was extremely fortunate to have all these very moral, caring, loving adults around me. I grew up with that, and it helped give me confidence about the world, and the goodness, in general, of people.

Fred McDarrah, photographer. Untitled (Baltimore Gay Alliance and Metropolitan Community Church of Baltimore during the Sixth Annual Gay Liberation Day March), New York, New York, June 29, 1975. Gift of the Goldman Sonnenfeldt Family, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

Another of McDarrah’s photos captures a group that traveled all the way from Baltimore to New York for the march (although the Charm City also hosted a Pride gathering in 1975, its first). Archivists at the Maryland Rainbow History Project were able to partially identify the sign-carrying woman and the man with his arm around her, courtesy of an oral history interview with Andre Powell, co-founder of the Baltimore Gay Youth Group. Thanks to them, we know that the young man in the photo was named Jack, and the woman, his mother, was “the first vocally gay-friendly parent” that Powell had ever encountered.

We also know that Jack, like Powell, was a member of the Metropolitan Community Church of Baltimore (founded 1972), and his t-shirt indicates his affiliation with the Baltimore Gay Alliance (founded 1975). This photo, then, also illustrates the nationwide growth of LGBTQ+ organizations, especially after Stonewall. For example, the first Metropolitan Community Church had been founded in Los Angeles in 1968 by Rev. Troy Perry; by the time the Baltimore branch was established four years later, there were 35 congregations—several in California, and also in New York, Miami, Dallas, Phoenix, Chicago, and Kaneone, Hawaii.

Fred McDarrah, photographer. Untitled (Larry Rivers at the Sixth Annual Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day), New York, New York, June 29, 1975. Gift of the Goldman Sonnenfeldt Family, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

The photo above is of Bronx-born Larry Rivers (1923–2002), a man of many talents who is most often remembered as a visual artist. Rivers had a profound influence on Andy Warhol, who described his painting style as “unique”— deeply informed by Abstract Expressionism and a forerunner of Pop Art. Rivers was also an accomplished jazz saxophonist, filmmaker, and poet; he had an intimate, personal, and artistically collaborative relationship with Frank O’Hara during the 1950s. (When O’Hara died unexpectedly in 1966, Rivers delivered a searing eulogy at his funeral, and created a striking memorial portrait which was based on a 1959 Fred McDarrah photograph.)

Beginning in the early 1960s, a growing boom in the American art market meant that “one could go into art as a career the same as law, medicine, or government,” as Rivers recalled in a 1980 interview. By 1963, he said, successful artists were “onstage… in the full glare of publicity,” and fortunately Rivers was well-suited to the spotlight—as Andy Warhol put it, “His personality was very Pop.” McDarrah's photo captured Rivers talking to a cameraman as they filmed the 1975 Pride March; the footage, which is part of the Larry Rivers Papers held at New York University Library’s Special Collections, highlights Rivers’ famously extroverted character. At one point, a young man with distinctive tattoos wandered past him, and Rivers exclaimed, “Here’s Tattoo Charley!” Charley, upon spotting the camera, responded with a mischievous grin, “Wanna see my fish?”

“Yeah! Let’s see the fish again,” Rivers yelled, at which point Charley gleefully unbuttoned his denim shorts and flashed a piscine tattoo that covered half his abdomen, from well above his navel down to his iliac crest. “There’s a lot more where that came from,” said Rivers appreciatively.

Fred McDarrah, photographer. Untitled (Charley Beckwith and Friend at the Sixth Annual Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day), New York, New York, June 29, 1975. Gift of the Goldman Sonnenfeldt Family, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

McDarrah took several photos of “Tattoo Charley” at the 1975 march. Charley (or Charlie) Beckwith was well-known to the city's photographers: Leonard Fink photographed him with Marsha P. Johnson in 1975 and inside the Ramrod leather bar in 1976, he posed nude for Peter Hujar in the same year, and Meryl Meisler captured him (and his fish) at the 1977 Pride March.

Fred McDarrah, photographer. Untitled (Larry Rosán at the Sixth Annual Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day), New York, New York, June 29, 1975. Gift of the Goldman Sonnenfeldt Family, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

Rivers also reacted with enthusiasm to the appearance of The Eulenspiegel Society, dashing headlong through the crowd to intercept leatherman Larry Rosán (pictured above) who was carrying the Eulenspiegel banner. Rosán greeted Rivers and his crew with a cheerful fist-pump and a “Hi there, everybody!” The Eulenspiegel Society (TES), founded in 1971, is the oldest BDSM organization in the United States and includes gay and straight people from across the full spectrum of BDSM sexuality. Rosán had been carrying their “Freedom for Sexual Minorities” banner since 1973. “This was a necessary part of the parade,” Rivers opined as the Eulenspiegelers marched past. “We should present all facets of sexuality.”

Zooming in on McDarrah’s photo allows us to catalog Rosán’s bandolier of pin-back buttons, which echo the sentiments expressed in Arthur Bell’s column and by many of Rivers’ interviewees: “Glad to be Gay,” “I'm Proud I'm Gay.” The buttons also indicate Rosán’s support for a number of other LGBTQ+ organizations, including the Gay Liberation Front, Gay Activists Alliance, and Church of the Beloved Disciple.

Left: Gay Liberation Front (1969–1972), Pin-back button, 1970–1972. Metal, paper, plastic. The New York Historical, Gift of Damien Taylor, 2018.36.4

Right: Pin-back button, ca. 1970. Metal, paper, plastic. The New York Historical, Gift of Damien Taylor, 2018.36.7

Several of these organizations convened at the West Side Discussion Group Center in the Meatpacking District, where Rosán was a staff writer for the West Sider. Between 1976 and the early 1980s, he contributed reviews of “Gay Meeting Places” and a series of short essays on “Gays & Prejudice.” But Rosán seems to have expressed himself most fully in the pages of Prometheus, TES’s magazine:

Let us Eulenspiegelers exult; let us S/M devotees make a joyful noise. For our fascinatingly extreme sadomasochistic scenes are not only celebrations of our own mystique, but also definite political acts—assertions of our basic freedom in the face of lingering but mythic garbage-ideas.

—Larry Rosán, Prometheus 5, 1974

Yet for all the conviviality on display, the 1975 march was not without tension. Even before Stonewall, homophile organizations had largely discouraged drag balls and “cross-dressing,” and in the 1970s, many gay men sought to challenge long-standing “pansy” or “fairy” stereotypes that pigeonholed them as campy and effeminate. It was, as the late Edmund White wrote in his 2025 memoir The Loves of My Life, the “period of the weight-lifting, hypermasculine clone.” It was also a time when gay sex was criminalized, cruising was illegal, and a broadly written 1845 New York State law on “criminal impersonation” was used to surveil, harass, and arrest people whose appearence did not conform with gender and class norms, and who might today identify as trans or queer. Only two years earlier, activist Sylvia Rivera had to fight her way up to the microphone at the 1973 Christopher Street Liberation Day rally at Washington Square Park, in order to deliver an impassioned speech on behalf of imprisoned trans women. “You tell me to go and hide my tail between my legs,” Rivera shouted. “What the fuck’s wrong with you all?” (The 1973 rally emcee, Vito Russo, eventually restored equanimity by calling Bette Midler to the stage.)

During the 1975 march, Larry Rivers interviewed several people who expressed frustration and a continued sense of marginalization within the gay liberation movement, including activist Lee Brewster. Brewster, the founder of Queens Liberation Front, publisher of Drag magazine, and proprietor of the Mardi Gras Boutique (which catered to drag queens) marched in a black floral dress and a broad-brimmed white hat tied with a yellow ribbon, carrying a fan pointedly painted with the words “I’m just a stereotype but I’m also proud.” Brewster explained to Rivers that the message was “a protest within a protest.”

At the end of the march, participants arrived in Central Park and settled in to eat, drink, smoke, chat, cruise, and enjoy a variety of speeches, live music, poetry recitals, and other performances. (At one point, Larry Rivers’ camera crew lost track of Larry Rivers, wandered off in search of him, and ended up interviewing Marsha P. Johnson and other members of the Hot Peaches Theater Company.) By the time the crew tracked Rivers down again, the clouds had opened up, ending the day on a festive, but rainy note.

The staff of the Center for Women's History hopes that the weather will be more cooperative during this year’s Pride March! Meanwhile, don't miss Fred McDarrah: Pride and Protest, on view at The New York Historical until July 13, 2025.

Fred McDarrah, photographer. Untitled (Participants at the Sixth Annual Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day March), New York, New York, June 29, 1975. Gift of the Goldman Sonnenfeldt Family, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

Written by Jeanne Gutierrez, Manager of Scholarly Initiatives