Vaccines offer protection against the germs we encounter everyday. While some deadly microbes have come and gone, others, such as influenza, have pestered New Yorkers for centuries. Major vaccination campaigns against smallpox, diphtheria, polio, and most recently, COVID-19 have saved countless lives. These efforts, often involving city-wide initiatives, have helped to control and eliminate infectious diseases in our metropolis. An installation in the Patricia D. Klingenstein Reading Room tells a compelling story about healthy cities, underserved populations, and disease prevention. Here are a few highlights from the installation.

Copy of a letter from George Washington to Dr. William Shippen Jr., February 20, 1777. The Patricia D. Klingenstein Library. The New York Historical.

America's first president initiated the first mass vaccination campaign in the United States. In February of 1777, George Washington ordered the mandatory inoculation against smallpox of all soldiers serving in the Continental Army. Washington’s decision did not come easily. Side effects from inoculation could last as long as five weeks, presenting a long recovery period Washington feared might make American forces vulnerable to British attack. Ultimately, the General decided that the deadly disease posed a greater threat than the British did. As he wrote to Dr. William Shippen Jr., “Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure, for should the disorder infect the Army…we should have more to dread from it than from the Sword of the Enemy.” Washington’s orders resulted in the successful inoculation of 40,000 soldiers by the end of that year.

Form of an address: recommended by the Trustees of the New-York Dispensary to be made to parents, by clergymen, at the baptism of children. [New York: s.n., 1810?].

Founded in 1791, The New York Dispensary served the sick and poor in New York City. This statement, issued in the first decades after Harvard Medicine School professor Thomas Waterhouse gained President Thomas Jefferson’s support for the Jennerian vaccination method, addressed New York City parents. If you “value the life of your infant, and the safety of your neighborhood, you will immediately avail yourselves of the advantage offered to you” by vaccination.

The Metropolitan Board of Health. Rules observed in offering free vaccination: May 31, 1869. The Patricia D. Klingenstein Library. The New York Historical.

In the late 1850s, public health advocates agitated for an independent municipal health department, one that was not under the control of the city’s elected officials. In February of 1966, the state passed a new law creating the Metropolitan Board of Health. One of the Board’s most urgent causes was to protect New York’s citizens from outbreaks of infectious disease. This notice, issued in 1969 by Sanitary Superintendent Elisha Harris, addressed smallpox as a killer that did not discriminate between the rich and the poor. Harris promised free vaccination to all New Yorkers. The flier directed city residents who did not have access through a family physician or the Dispensary to locate their district’s designated vaccination spot for daily access to inoculation services.

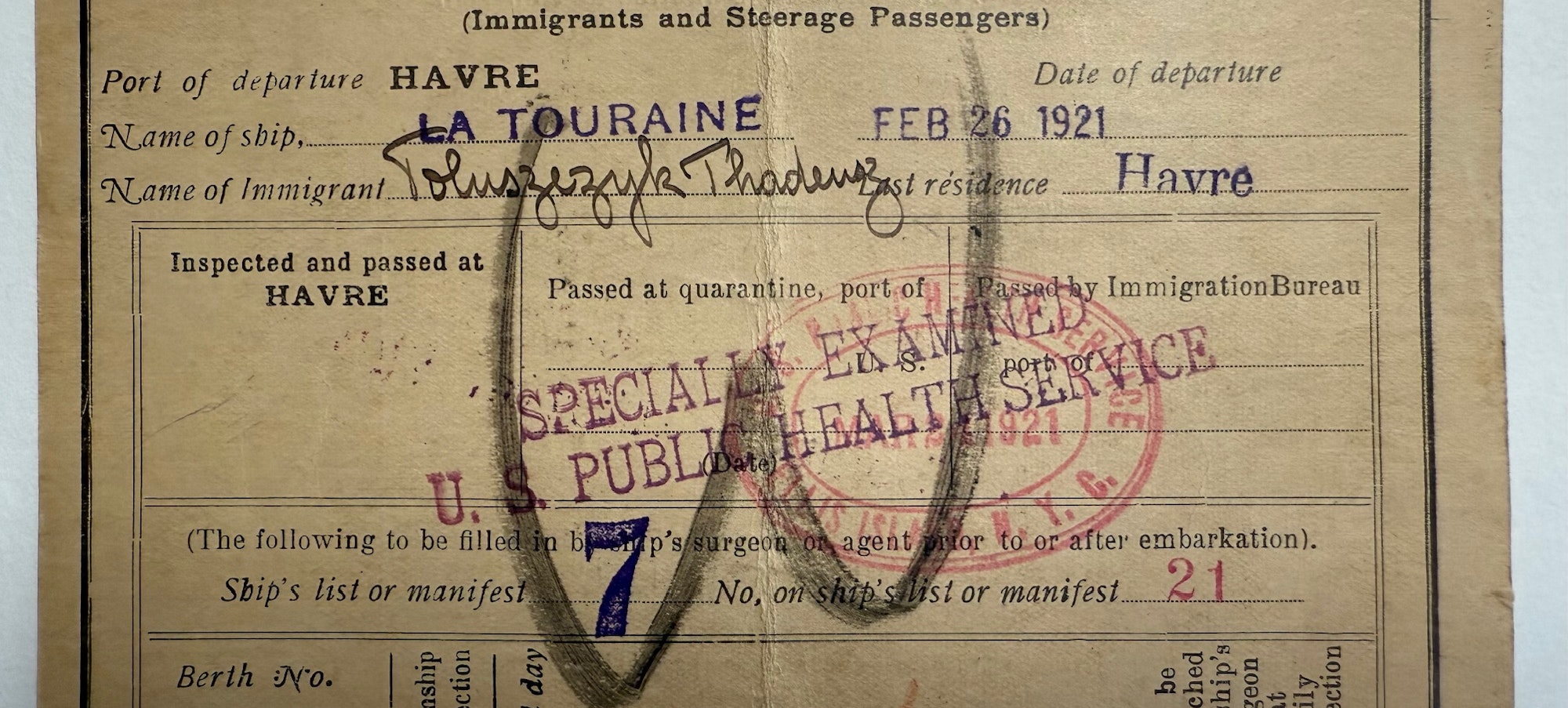

Card with proof of vaccination issued by the French shipping company Compagnie Générale Transatlantique for his passage on the French steamer La Touraine. The Tadeusz P. Foluszczyk Papers. Unprocessed collection. The Patricia D. Klingenstein Library. The New York Historical.

Inspection card issued by the French shipping company Compagnie Générale Transatlantique held by Polish immigrant Tadeusz P. Foluszczyk during his passage to America on the French steamer La Touraine. The Tadeusz P. Foluszczyk Papers. Unprocessed collection. The Patricia D. Klingenstein Library. The New York Historical.

As the gateway to America for hundreds of thousands of immigrants, many of New York City’s newest Americans were asked to show proof of vaccination. Tadeusz P. Foluszczyk, born in Leipzig, Poland, in October of 1902, immigrated from the French city of Tours to the United States in February of 1921. A medical card issued by the French shipping company Compagnie Générale Transatlantique for his passage on the French steamer La Touraine indicates that Foluszczyk was given vaccinated status when he boarded the liner. On the back, the card advises passengers to keep it to avoid detention at quarantine and on railroads in the United States in French, German, and Italian. An inspection card indicates that Folus was examined by the U.S. Public Health Service at Ellis Island.

Vaccination certificate for Joseph Keppler, 1840. The Keppler Family Papers. The Patricia D. Klingenstein Library. The New York Historical.

Like the Polish immigrant Foluszczyk, the Austrian artist Joseph Keppler arrived with proof of vaccination. Keppler, a cartoonist and founder of Puck Magazine, immigrated in 1867 to St. Louis, Missouri, with his family from Vienna. Born in 1838, he was vaccinated for smallpox at age two. Among the important documents he brought with him when he arrived in the United States was this vaccination certificate, attesting to his inoculation in 1840.

The Maltine Company, Quarantine Sketches, [1902]. The Patricia D. Klingenstein Library. The New-York Historical.

The Maltine Company’s promotional advert, Quarantine Sketches, supplies visual documentation of the medical examination of immigrants arriving at the Port of New York at the turn of the century. Since 1891, United States Public Health Service physicians have evaluated the health of all the immigrants entering New York through a line inspection. These doctors – who had to observe between 2,000 and 5,000 new arrivals in a single day - looked both for signs of disease and for vaccination scars. The Maltine Company’s assertion that all passengers who disembarked at Ellis Island were “vaccinated before they leave their native land” was more aspirational than true. It was not until 1944 that the International Sanitary Convention developed the first International Certificate of Vaccination, significantly increasing the number of vaccinated travelers.

These and other collection items are on display in the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library through December 15, 2025.