The holiday shopping season is coming to a close, though our email inboxes are still overflowing with last-minute deals and tempting advertisements. But rather than perusing yet another "Best of 2025" gift list, we at the Center for Women's History are looking further back, casting a historian's eye over the playthings that past generations of parents have provided for their children.

After all, how do children decide what to be when they grow up? One of our past installations, 2024's Child's Play explored this question with a display of toys meant to entertain but also instruct: toys that introduced children to adult roles, which have historically been deeply gendered.

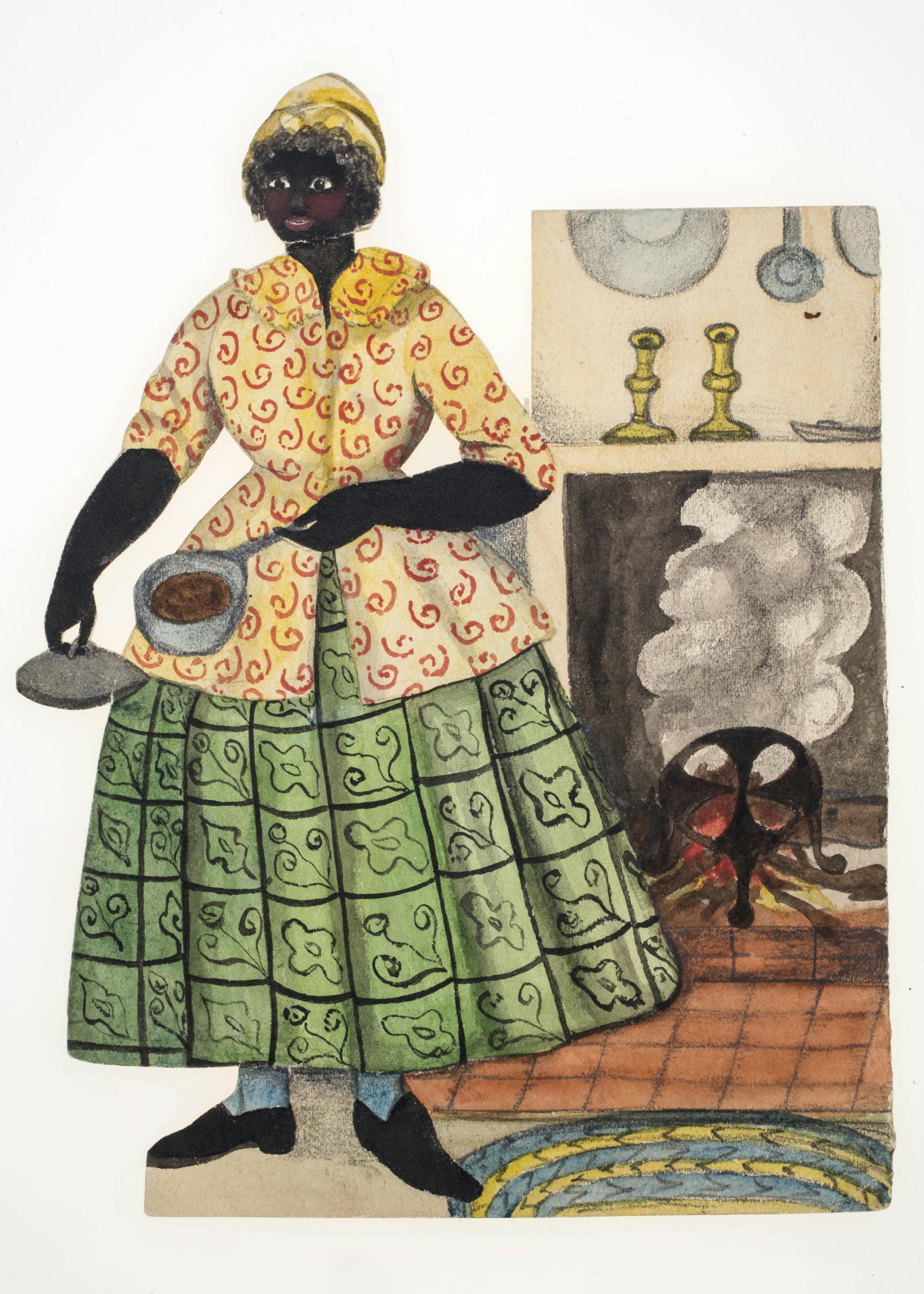

Take, for example, the handmade paper doll pictured below, one of a set made in Quebec around 1855. As a group, the dolls depict women doing the kinds of domestic work that would have been quite familiar in the 19th century: cooking, gardening, serving and preserving food, sewing clothes, carding wool, and spinning yarn—often with children and pets playing underfoot.

Unidentified maker. Paper doll, ca. 1855. Watercolor and graphite on paper. The New York Historical, Purchased from Elie Nadelman, INV.10267nn

This particular set of paper dolls also shows women engaged in art work, such as watercolor painting and needlepoint. These skills were part of elite girls' education, and many affluent women engaged in such pursuits in their leisure time. However, the mid- to late 19th century also saw a number of philanthropic efforts that aimed to help women translate their artistic skills for the marketplace by opening design schools for women, located in urban centers such as London, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, New York, and Cincinnati. These schools offered professional training in the decorative arts for "deserving" women in need of "genteel" occupations.

Unidentified maker. Paper dolls, ca. 1855. Watercolor and graphite on paper. The New York Historical, Purchased from Elie Nadelman, 1937. 1937.1794b and 1937.1794e

The 19th century's periodic financial panics, followed by the mass casualties of the Civil War, left thousands of American women widowed or unmarried. These economically vulnerable women needed work that would allow them to financially support themselves, but could ideally be “practiced at home, without materially interfering with the routine of domestic duty,” as Sarah Peter, founder of the Philadelphia Design School for Women put it. Students at these schools trained as commercial artists, art teachers, engravers, and designers of “china and silver, carpets, chintz curtains, wall papers, oil-cloths and upholstery, dress fabrics and trimmings, illustrated books,” and all sorts of home goods. In the September 1852 issue of the popular magazine Godey's Lady's Book, author Alice B. Neal asserted that such design work, despite being “a business entirely monopolized by men,” was actually “better suited" for women, because it “demands little physical strength, but the most delicate manipulations."

In addition to depicting certain kinds of work as "women's work," 19th- and early 20th-century toys often added a racial dimension: Black women were most commonly represented as maids or cooks. This stereotype permeated American visual and popular culture throughout the 1800s and into the 1900s, persisting well after the abolition of slavery.

First: Unidentified maker. Paper doll, ca. 1855. Watercolor and graphite on paper. The New York Historical, Purchased from Elie Nadelman, 1937. INV.10267m

Second: Possibly Julia Jones Beecher (1826–1905), Missionary Rag Baby, 1893–1910. Stockinette, cotton, yarn, paper, paint. The New York Historical, Gift of Helen Graham Fairbank Goodkin, 2022.16

In 1893, Julia Jones Beecher—sister-in-law to Uncle Tom's Cabin author Harriet Beecher Stowe—began upcycling used stockings to create dolls characterized by a prominent brow, painted eyes, and curly yarn hair. These "Beecher-type" dolls were sold via mail-order and at charitable functions nationwide to raise money for missionary work sponsored by the Independent Congregational Church of Elmira, New York, where Beecher's husband served as the minister. While "Beecher-type" dolls made out of white stockings depicted babies, the dolls made out of black stockings, like the one above, portrayed adult women who were usually equipped with aprons. This reflected the widespread caricature of Black women as subservient “mammy” figures, always ready to perform domestic work in white households: cooking, cleaning, and caring for white children.

Unidentified maker. Toy cupboard with pewter dishes, 1850–1900. Wood, brass, pewter. The New York Historical, Gift of Katharine Prentis Murphy, 1961.35a-s

Though handmade toys persisted, the 19th century also saw rapid advances in manufacturing, materials, and transportation that made commercially-produced toys cheaper and more accessible. Germany, a center of toy production as early as the 1500s, dominated the American market, with importers bringing in toys of all kinds, from miniature kitchens to tin soldiers to plush animals. (About two-thirds of the toys sold in the United States came from overseas—at least until the outbreak of World War I cut off European toy imports and shifted centers of production towards the United States.)

German and French manufacturers had long been particularly noted for their high-quality dolls, initially cast in wax and ceramic, though later dolls were also made of celluloid. In the mid-1800s, manufacturers began producing dolls that resembled children and babies, encouraging their young owners to care for the dolls as if they were real infants. Of course, this also necessitated the purchase of clothes and accessories, such as doll-sized cradles, strollers, high chairs, and feeding bottles.

(First) Possibly J. D. Kestner, Jr. (German), maker. Doll, ca. 1895. Ceramic, leather, textile, hair, paint. The New York Historical, Gift of Richard E. Davis, 1961.21

(Second) Bru. Jne. & Cie (French), maker. Baby doll, 1880-90. Ceramic, textile, leather, glass, hair, paint. The New York Historical, Gift of Miss Hortense Abbott Carney, 1923.80

Meanwhile, changes in education and family structure helped further increase the demand for toys: increasing numbers of people moved from rural to urban areas, more opportunities opened up for women who wanted to work outside the home, and child mortality drastically decreased (in large part because of advances in health care and sanitation; for example in the supply of milk). These, among many other factors, lead to a drop in the nation's overall fertility rate—thus allowing parents to devote more resources to fewer children. Additionally, the arrival of the kindergarten movement from Germany in the second half of the 19th century encouraged parents and teachers alike to provide young children with opportunities for creative play. In short, toys were increasingly understood as an important part of children's education and development.

McLaughlin Brothers (American, 1854–1921), maker. The Jolly Game of Old Maid, ca. 1890. The New York Historical, Liman Collection, 2000.636.

This children's card game poked fun at different workers, including women such as "Miss Crosswires" the telephone switchboard operator and "Miss Botche Misfit" the seamstress.

McLaughlin Brothers (American,1854-1921), maker. The Game of Playing Department Store, 1898. The New York Historical, Liman Collection, 2000.715.

This game introduced children to department stores: luxurious emporiums carrying all sorts of goods and catering to fashionable, middle-class women who enjoyed shopping, dining, and socializing in a safe, genteel environment. By the late 1800s, shopping was considered such a gendered activity that New York City's retail district was popularly known as "The Ladies' Mile."

McLaughlin Brothers (American,1854-1921), maker. Round the World with Nellie Bly, ca. 1890. The New York Historical,Liman Collection, 1992.12.17.

This game is based on the adventures of Nellie Bly (Elizabeth Cochrane), a famous American journalist, who successfully broke the fictitious record for traveling around the world set by Jules Verne's character Phineas Fogg in Around the World in Eighty Days.

The American toy industry really took off in the mid-20th century, which saw a confluence of propitious factors: the post-World War II baby boom, which increased demand, and the introduction of cheap, durable, and colorful plastics that facilitated an explosion of low-cost products, many of which were manufactured overseas in countries with low labor costs. Meanwhile, the rapid embrace of television would eventually allow advertisers to reach growing numbers of young consumers directly (in 1952, Mr. Potato Head became the first toy to be advertised on TV) while also providing a platform for popular characters that toymakers were quick to license.

Whitman Publishing Co., I Love Lucy paper doll, 1953. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

Over the course of six popular seasons, actor and comedian Lucille Ball portrayed her sitcom alter ego, Lucy Ricardo, as a housewife haplessly attempting to break into show business.

Fisher-Price (founded 1930), maker. Play Family Sesame Street, 1975–78. The New York Historical Purchase, 2016.52

The first woman character to appear on Sesame Street was Susan, played by Dr. Loretta Long and initially portrayed as a housewife. In 1972, the National Organization for Women (NOW) coordinated a letter-writing campaign asking the Children's Television Workshop to broaden the portrayal of women and girls on Sesame Street, and more women soon joined the cast—including librarian Linda and photographer Olivia.

By the early 1970s, the women's liberation movement began to take on toys a feminist issue, calling for the elimination of sexist and racist toys, packaging, and advertising. Ms. magazine editor Letty Cottin Pogrebin, a vocal advocate for racially inclusive, non-sexist children's toys, books, and media, urged readers to use their "consumer power" to reject sexist and racist toys. The National Organization for Women (NOW) demonstrated outside of industry conventions and toy stores, organized educational campaigns and product boycotts, and formed a consumer advocacy group called Public Action Coalition on Toys. NOW also collected data showing that educational toys (such as science kits) were generally marketed to boys, while girls got toy kitchenware, irons, and vacuums.

These activists were joined by the Women's Action Alliance, which began developing a guide to Non-Sexist Early Childhood Education in 1972—the same year that Marlo Thomas and the Ms. Foundation for Women put out the bestselling Free to Be… You and Me album, featuring songs like "William's Doll" that pushed back against gendered expectations of children. When the Women's Action Alliance published its non-sexist curriculum in 1974, Free to Be was on its list of recommended materials. In that same year, Milton Bradley released a line of non-sexist, racially inclusive toys, like the paper dolls pictured below, that were created in partnership with WAA curriculum author Barbara Sprung.

Milton Bradley Company (American, 1860–2009), maker. Our Helpers, 1974. The New York Historical

However, many toys and toy advertisements maintained traditional gendered stereotypes. As Tarpley Hitt writes in her new book Barbieland: The Unauthorized History, 1981 saw the debut of both He-Man, a "space epic superhero" whose figure was "so cartoonishly bulky it bordered on pornographic," and Pretty & Pink Barbie, dressed in "head-to-toe tulle." (On the other hand, Barbie is in some sense the ultimate working woman: since her debut in 1959, when she was introduced as a professional fashion model, she has been outfitted for hundreds of different careers, including astronaut, engineer, doctor, dentist, veterinarian, Air Force pilot, and NASCAR driver. She also ran for president in 1992.) In 2000, Disney launched the ubiquitous Disney Princesses line, now widely reported to be one of the highest-grossing franchises in history, and Bratz fashion dolls were introduced a year later, grossing $2 billion in sales during their first two years on the market despite an American Psychological Association Task Force report on the sexualization of young girls specifically citing the Bratz dolls' clothing ("miniskirts, fishnets, and feather boas") as harmful.

The late 2010s saw a brief push for more inclusive toys, with major brands like Lego and Mattel pledging to address the issue; Mattel, for example, introduced a line of gender-neutral dolls in 2019, which joined 2016's line of "Fashionista" Barbies and Kens, which featured diverse body types, skin tones, and hairstyles. In 2021, the state of California even passed Assembly Bill 1084, requiring retailers to provide gender neutral toy sections. It went into effect with little fanfare on January 1, 2024.

Toys are fun, and an indisputably important part of the holiday season, but the multi-billion dollar industry has a deeply serious side as well. They suggest aspirational adult roles, reflecting and reinforcing what children see as possibilities for their own futures. In today's terms, you have to "see it to be it." Tracing how women’s labor as represented in toys and games has changed significantly over time shows us how societal conceptions of gender roles have changed too.

Written by Jeanne Gutierrez, Manager of Scholarly Initiatives, Jean Margo Reid Center for Women’s History