Are you waiting for the start of the 2026 Winter Olympics? If so, you probably didn't miss the online frenzy surrounding two of this year's Olympic torch-bearers: Hudson Williams and Connor Storrie, co-stars of Heated Rivalry—the runaway hit show about a scorching romance between two closeted professional hockey players.

If you're old enough to watch Heated Rivalry but haven't yet done so, please stop reading right now and go do that. We'll wait—at least until you've finished Episode 2, "The Olympians."

True to its title, the plot of "The Olympians" is driven by the two leads' presence at the 2014 Winter Games in Sochi, Russia. Shane Hollander (Williams) is just happy to be there, playing for Team Canada, but Ilya Rosanov (Storrie), is crumbling under the pressure of serving as captain of the Russian men's national team. Much to Rosanov's dismay (and his ultranationalist father's disgust) the Russian team performs poorly and exits the competition early.

However, "The Olympians" also makes it clear that there is another source of tension plaguing poor Ilya: as a bisexual man in Russia, he must remain closeted for his own safety. The episode alludes to the impact of Russia's real-life "gay propaganda" law, passed in June 2013, which forbade discussion of “nontraditional” sexual relationships, and is hinted at in a conversation between Hollander and fellow hockey players Scott Hunter (François Arnaud) and Carter Vaughn (Kolton Stewart). As they make plans to attend a men's figure skating event, Vaughn, assuming that some of the figure skaters might be gay, compliments their bravery in attending the Olympics and remarks, "Russia is not safe for folks like that."

HEATED RIVALRY Season 1, Episode 102, Nov. 28, 2025. From left: François Arnaud (Scott Hunter), Hudson Williams (Shane Hollander), Kolton Stewart (Carter Vaughn). Photo ©HBO Max / Courtesy Everett Collection

What the show doesn't mention is that the run-up to Sochi, and the Winter Games themselves, were marked by international protests and activism targeting Russian officials, international sporting organizations, and Olympic sponsors. One campaign, named after Principle 6 of the Olympic charter which prohibits "discrimination of any kind," garnered over 50 Olympian and Paralympian co-signers. Tennis legend Billie Jean King, hockey player Caitlin Cahow, and figure skating champion Brian Boitano were named to the US Olympic delegation by President Barack Obama, who confirmed that the inclusion of these openly gay athletes was intended as a rebuke to the Russian propaganda law. Despite the hostile climate (for example, Russia prohibited the opening of an Olympic Pride House), seven openly gay athletes—all women—competed at Sochi. Among them was Dutch speed skater Ireen Wüst, who medaled five times. With two gold and three silver, she was the most decorated athlete of the 2014 Games.

Thanks to the activism of athletes and others, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) updated Principle 6 in December 2014 to include non-discrimination with regard to sexual orientation in the Olympic charter and included it in host city contracts as well. The number of openly gay Olympians ticked up: 56 in Rio, 15 in Pyeongchang, 186 in Tokyo, 36 in Beijing, and nearly 200 in Paris. (The Summer Games have more events and more athletes than the Winter Games, hence the wide range of numbers.)

Yet LGBTQ+ athletes were already an integral part of the modern Olympic Games and had been for decades. As Michael Waters makes clear in his 2025 book, The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports, an intense debate over the intersection of sex, sexuality, gender, and sports took place in the late 1920s and 1930s. As more and more women began to participate in competitions, some successful athletes—like the Japanese track star Hitomi Kinue, who won a silver medal in 1928—faced accusations that their bodies were too masculine. In the mid-1930s, the Czech runner Zdeněk Koubek and the British shot-putter Mark Weston transitioned from living as women to living as men, dressing in men's attire and becoming romantically involved with women. Although neither athlete sought to participate in women's competitions after transitioning, the Nazi government, some doctors, and some international sports officials (including Avery Brundage, a future President of the IOC), cited them as evidence in favor of conducting medical examinations in the run-up to the 1936 Berlin Games—thus making the Olympics "one of the first global institutions to enshrine into practice gender surveillance," as Waters points out. Because the policy impacted women athletes only, Waters adds, it would allow officials to "eliminate anyone they wanted, just by calling that athlete's femininity into question." That almost happened to Helen Stephens, a six-foot tall American track-and-field competitor. After she won gold in the 100 meter dash, rumors began to circulate that Stephens was secretly a man, citing her height, her deep voice, and her size 10 ½ shoe. (Stephens was also romantically attracted to women, but she never acknowledged this publicly.) One reporter even tracked down Helen's mother in Missouri to ask about her daughter's sex, to which Mrs. Stephens replied indignantly that Helen was "absolutely a girl."

Unidentified photographer. Helen Stephens (US) winning 100 meter, Olympic games, Berlin, 1936. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Of course, under the Nazi's racist and eugenicist policies, the 1936 Olympics did not only seek to exclude "masculine" women: Greta Bergmann, one of Germany's best high-jumpers, was barred from competing because she was Jewish, and the German track-and-field star Otto Peltzer, whose homosexuality was "an open secret," spent the first half of the Games in jail. He would later be imprisoned in Mauthausen, where men convicted under Paragraph 175 of Germany's criminal code (which forbade sex between men) were forced to labor in granite quarries.

After the wartime cancellation of the 1940 and 1944 Games, the Olympics returned in 1948. By then, the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF, now World Athletics), the international body governing track and field, had begun to require that all women competitors—not only those whose femininity had been challenged—submit medical certificates attesting to their sex. Over the next few decades, other sports would adopt similar rules, in part because of Cold War geopolitics: US outlets praised American women as "mighty attractive practitioners" of their sports, while condemning athletes from the USSR as fraudulent "female-looking boys" of "questionable femininity."

We know of very few LGBTQ+ athletes who participated in the Olympics during the post-WWII "Lavender Scare" years. Those who did compete—for example, figure skater Ronald Robertson, a 1956 Olympic silver medalist who was in a long-term relationship with Hollywood heartthrob Tab Hunter—could not be open about their sexuality. At the time, gay men and lesbians were widely pathologized, discriminated against, purged from the military and government offices, and excluded from many other types of employment. While sports clubs and leagues offered some space for community and recreation, it was not until the growth of the gay liberation movement in the late 1960s and 1970s that groups for LGBTQ+ athletes, like New York's Big Apple Softball League (founded 1977), began to form. Still, for many years, acceptance remained elusive and uncertain. Widespread homophobia, exacerbated in the 1980s by misinformation and stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS, meant that elite athletes who identified as LGBTQ+ faced significant disadvantages—for example, when Billie Jean King was outed in 1981, she lost $2 million in endorsements overnight. As a result, many Olympic athletes waited to come out until after their Games were over. To give just one instance, Sheryl Swoopes and Jennifer Azzi, both members of the undefeated Team USA women's basketball squad that won gold at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics and kicked off a winning streak of eight consecutive Olympic victories, did not feel able to come out publicly until 2005 and 2016, respectively.

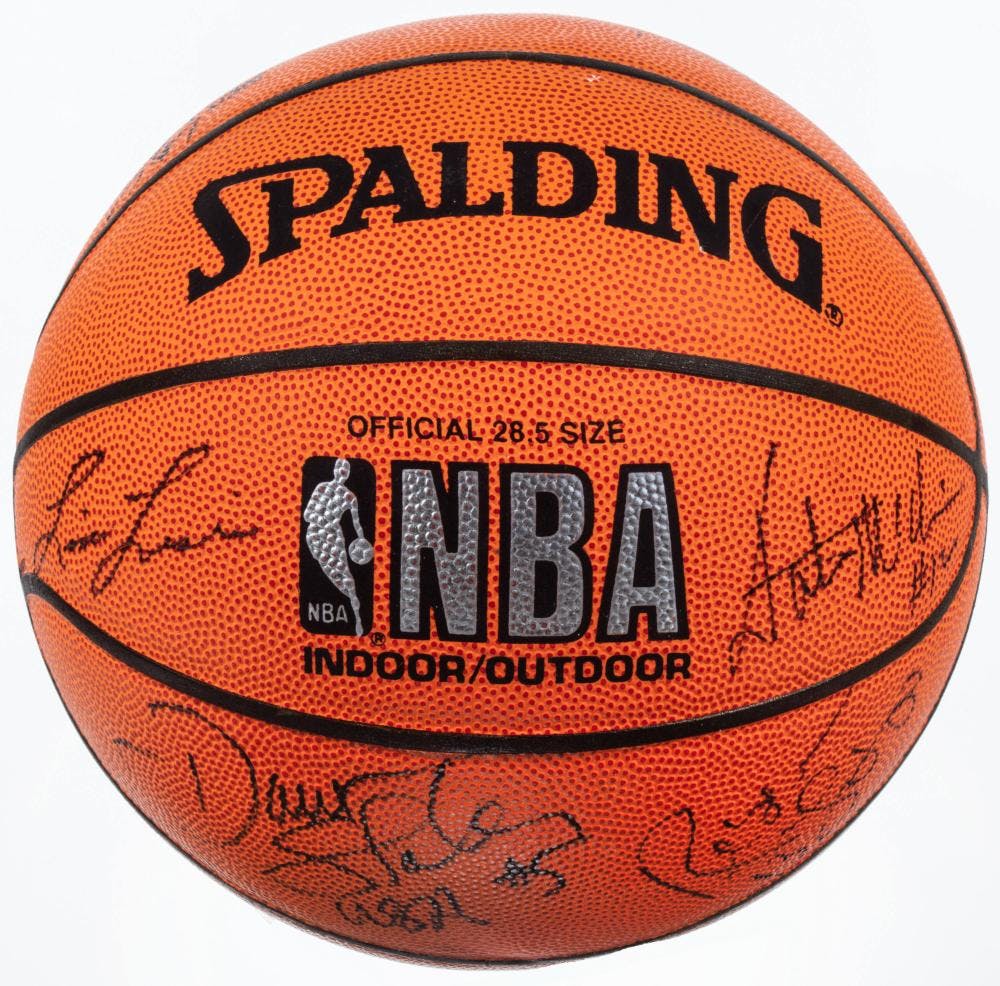

A. G. Spalding & Bros., founded 1876. Basketball autographed by US Women's Basketball Olympic Team, 1996. Rubber. The Women’s Sports Foundation Records, 2019.75.256

Greg Louganis, the champion diver who won gold at the 1984 and 1988 Olympics, chose to come out at the opening ceremony of the 1994 Gay Games, a venue where LGBTQ+ athletes of every skill level could compete. (It was not officially known as the Gay Olympic Games, thanks to a lawsuit by the US Olympic Committee). Founded in 1982 by Olympic decathlete Dr. Tom Waddell, and with key support from entrepreneur and sports enthusiast Rikki Streicher, the first Gay Games took place at Kezar Stadium in San Francisco; the torch run that brought the Gay Games flame began at the Stonewall Inn in New York. An international group of 1,350 athletes competed over nine days in events ranging from billiards to wrestling. The second Gay Games was also held in San Francisco, while the third went north to Vancouver.

Robert Pruzan, photographer. Rikki Streicher, Tom Waddell, and Sara Lowenstein marching at the Opening Ceremonies of the second Gay Games, 1986. Robert Pruzan Collection (1998–36), Courtesy of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society

The opening of Gay Games IV in New York City coincided with the 25th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising. With 31 sports and 12,500 participants from 40 nations, the Games spread over 30 venues across the city, including Columbia University’s Baker Field/Wien Stadium, where Donald MacIver carried this flag during the Opening Ceremonies. MacIver, a Green Beret and Vietnam War veteran, was also president of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual Veterans of Greater New York (a chapter of today’s American Veterans for Equal Rights) and advocated for the repeal of the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, which prevented gay men and lesbians from serving openly in the armed forces.

Steve Boyd, designer. Gay Games flag carried by Donald MacIver, 1994. Synthetic fabrics. The New York Historical, 2024.24.2

Left: Unidentified designer. Gay Games IV pin, 1994. Metal, enamel. Gift of Janice L. Schachter, 2024.23.8

Right: Unidentified designer. Participant pin, 1994. Metal, enamel. Gift of Janice L. Schachter, 2024.23.7

Janice L. Schachter, an IT professional and amateur tennis player, volunteered and competed in tennis as a member of Team New York at the 1994 Gay Games.

Later in the 1990s, the Gay Games went overseas, with Amsterdam hosting. The Games have since been held in Sydney, Chicago, Cologne, Cleveland, and Paris. The number of participants has held steady, with the 2023 Games in Hong Kong and Guadalajara welcoming 10,300 participants from 102 countries, who participated in 55 sporting and cultural events. We'll have to wait until this summer to see the 12th Gay Games, which will take place in Valencia, Spain.

This week, though, The Center for Women's History will be rooting for Team USA, watching as a record number of LGBTQ+ athletes skate, ski, and snowboard their way through Milano Cortina.

Written by Jeanne Gutierrez, Manager of Scholarly Initiatives, Jean Margo Reid Center for Women’s History