Margaret Bourke-White never let an important moment escape her. A pioneer in the field of photojournalism, she worked across genres, beginning in commercial and industrial photography, before transitioning to documentary photo books and essays, eventually working as an overseas war correspondent.

During World War II, “Maggie the Indestructible” was accredited by the US Armed Forces as a photographer and carried her camera across Europe with an authority befitting a military commander. She coaxed a smile out of Stalin, photographed German air raids on the Kremlin, and was with the Allied troops when they liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp in 1945. After the war, Bourke-White photographed Gandhi at his spinning wheel in 1946 and scenes of apartheid in South Africa.

She was in Korea in 1952 when she first received a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. She pursued new photography assignments after her diagnosis and published her autobiography, Portrait of Myself, in 1963 before passing away due to complications from the disease on August 27, 1971, at the age of 67.

Bourke-White did not intend for photography to become her profession. But picking up a camera in college changed her mind. When her photographs of steel mills and industrial buildings in Cleveland caught the attention of Henry Luce, the founder of LIFE, Fortune, and TIME magazines, she was still early in her career. It had only been a few years since, according to her autobiography, “the Bourke-White Studio was a name on a letter-head and a stack of developing trays in the kitchen sink” (Portrait of Myself, 35).

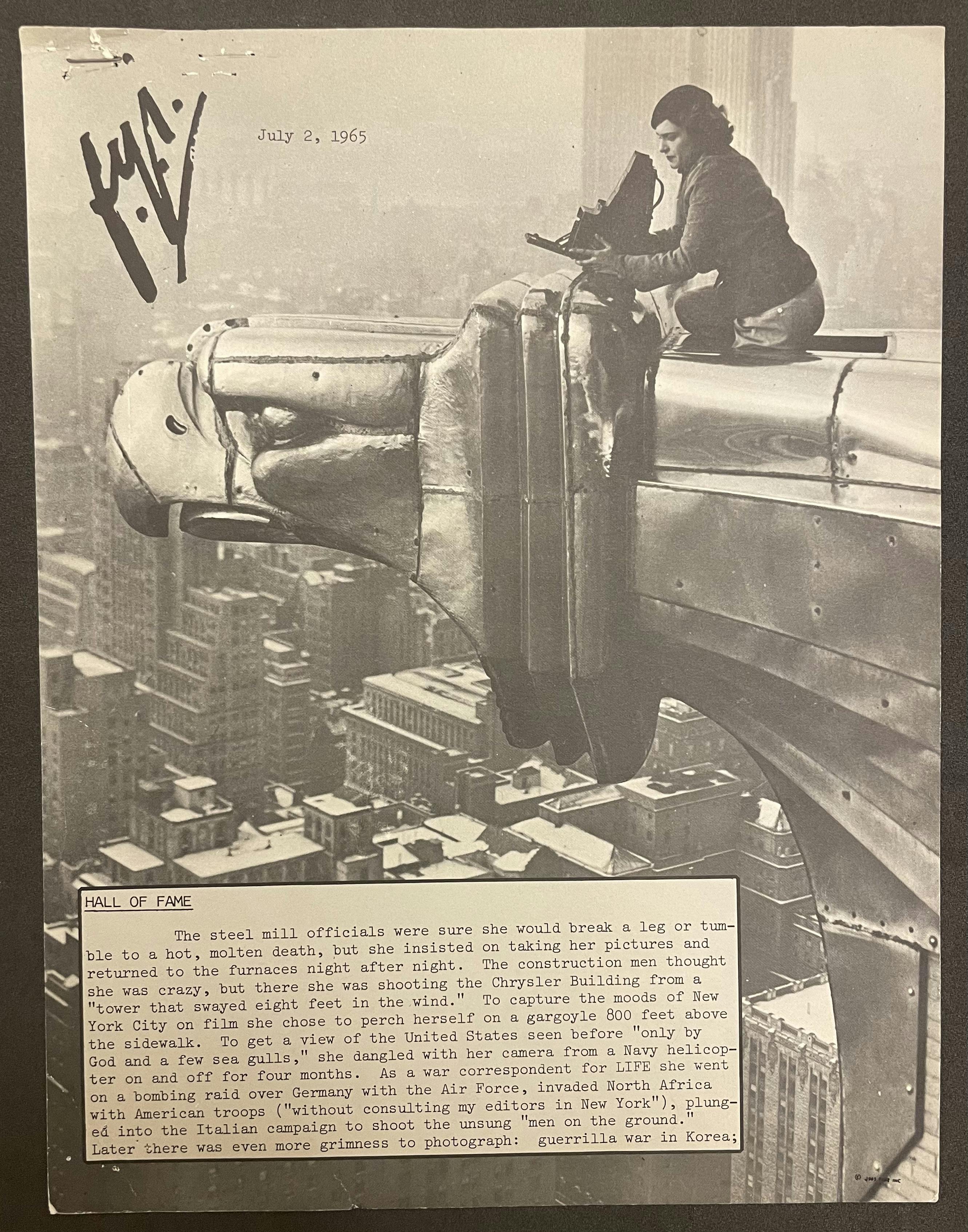

By 1930, Bourke-White had secured a freelance position with Fortune magazine and moved into offices on the 61st floor of the Chrysler Building. She befriended the stainless steel gargoyles that lived outside of her window (affectionately nicknamed “Bill” and “Min”), and even found opportunity to take her camera out onto one of the Art Deco beasts to capture images of New York City’s changing skyline.

Bourke-White perched atop an Art Deco gargoyle just outside of her studio on the 61st floor of the Chrysler Building on Lexington and 42nd Street circa 1930. This 1965 issue of FYI included a profile of Bourke-White along with the photograph. Time Inc. records, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New-York Historical Society.

The Patricia D. Klingenstein Library holds a number of Bourke-White's letters from this era, all part of the Time Inc. records. What they reveal is a businesswoman and creator at work, battling to preserve the pay and credit she felt she deserved for her images. She was not afraid to negotiate her terms with a friendly bit of verbal sparring. Fortune managing editor Ralph Ingersoll became just one object of her playful combativeness. In a letter from 1935, he chided her for not properly writing a caption. Her response?

“Come, come now. How do you define a good caption, teacher? And, don’t you think it would be more regular, besides being more fun for me, if I could know the penalties for my transgressions in advance?”

In another telegram, written after Bourke-White had not received proper attribution for her work, she declared, “Let’s have a cocktail. I’m upset to the point of tears.”

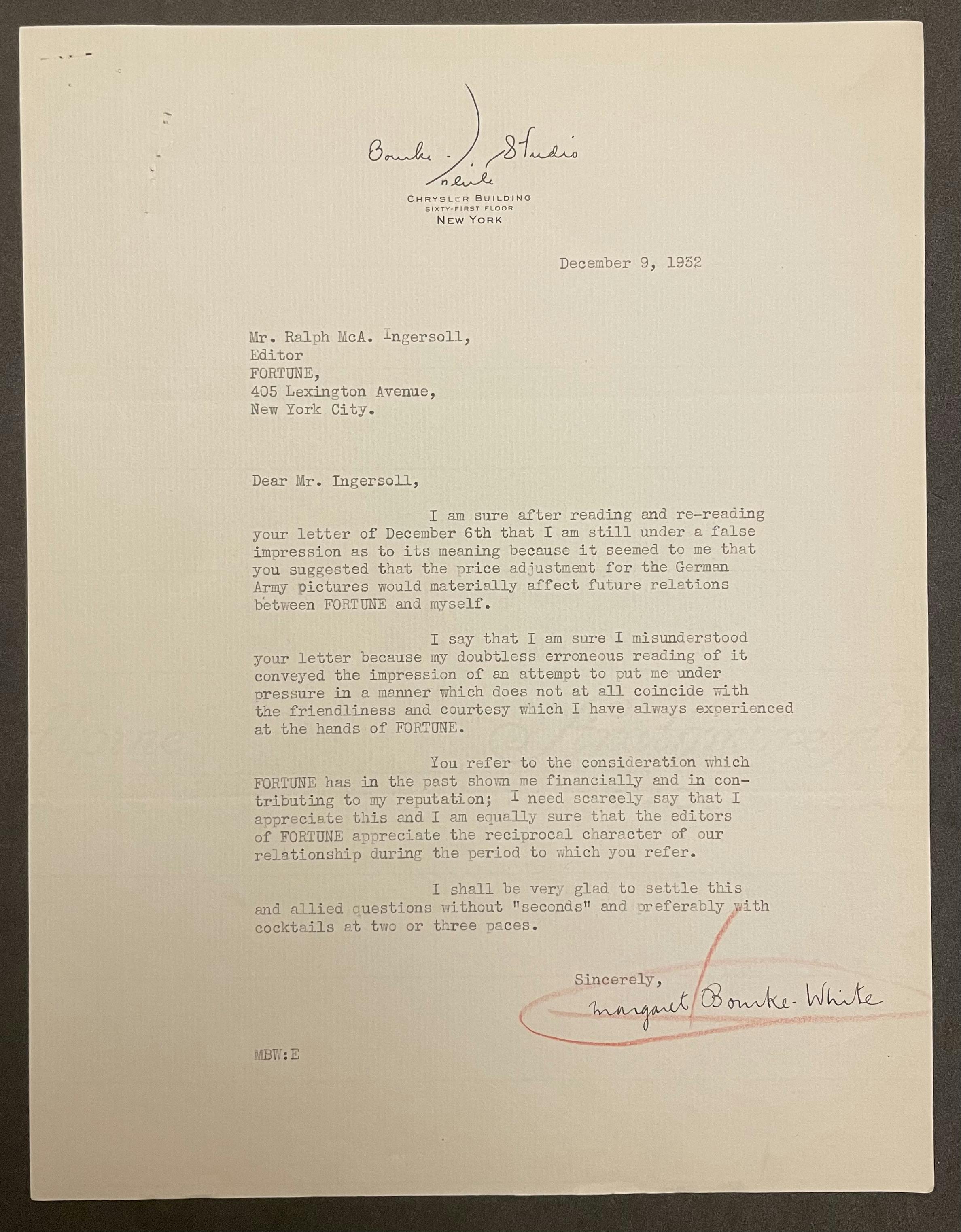

A set of letters from 1932 regarding a photo series of the German army, however, shows Margaret Bourke-White going toe-to-toe with Ingersoll in true His Girl Friday fashion.

Initially, in a December 2 letter, Ingersoll admitted that the reason her German army pictures series had not been reviewed yet was largely his own fault:

“The life and hours of an editor of FORTUNE remain complex affairs. I should long since have gotten in touch with you about your German Army pictures. The fact was, however, that I returned from a vacation with three weeks to close a January issue and I put it off.”

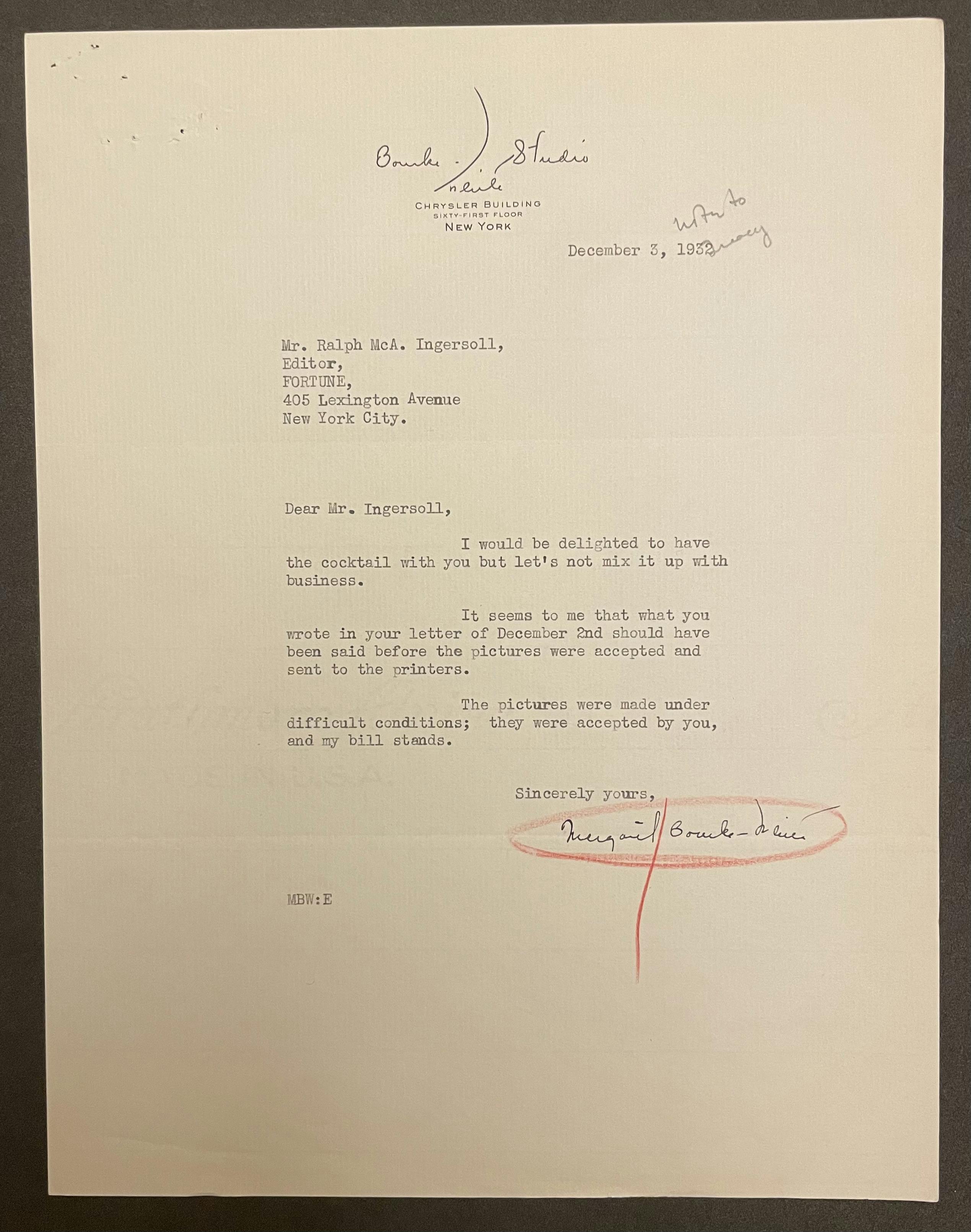

Upon Ingersoll’s suggestion of a cocktail to smooth things over, Bourke-White set her terms:

“I would be delighted to have the cocktail with you but let’s not mix it up with business…The pictures were made under difficult conditions; they were accepted by you, and my bill stands.”

Margaret Bourke-White’s December 3, 1932 letter to Ralph Ingersoll. Time Inc. records, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New-York Historical Society.

If Bourke-White seemed to assert herself forcefully, it is important to note that her freelance position was far from stable, a state that would hold true even into her years working at LIFE magazine. Later, and in spite of LIFE’s reputation as a photography magazine, Luce was quite reluctant to hire a full-time photography staff. Many of the photographers worked freelance and the types of photographs and the expenses incurred differed significantly between different photographers. For example, another prominent LIFE contributor Alfred Eisenstaedt used a handheld 35mm camera and could easily deliver 3,000 frames per story, in comparison to Bourke-White’s large-format film, which might deliver only 50 to 100 frames for a story.

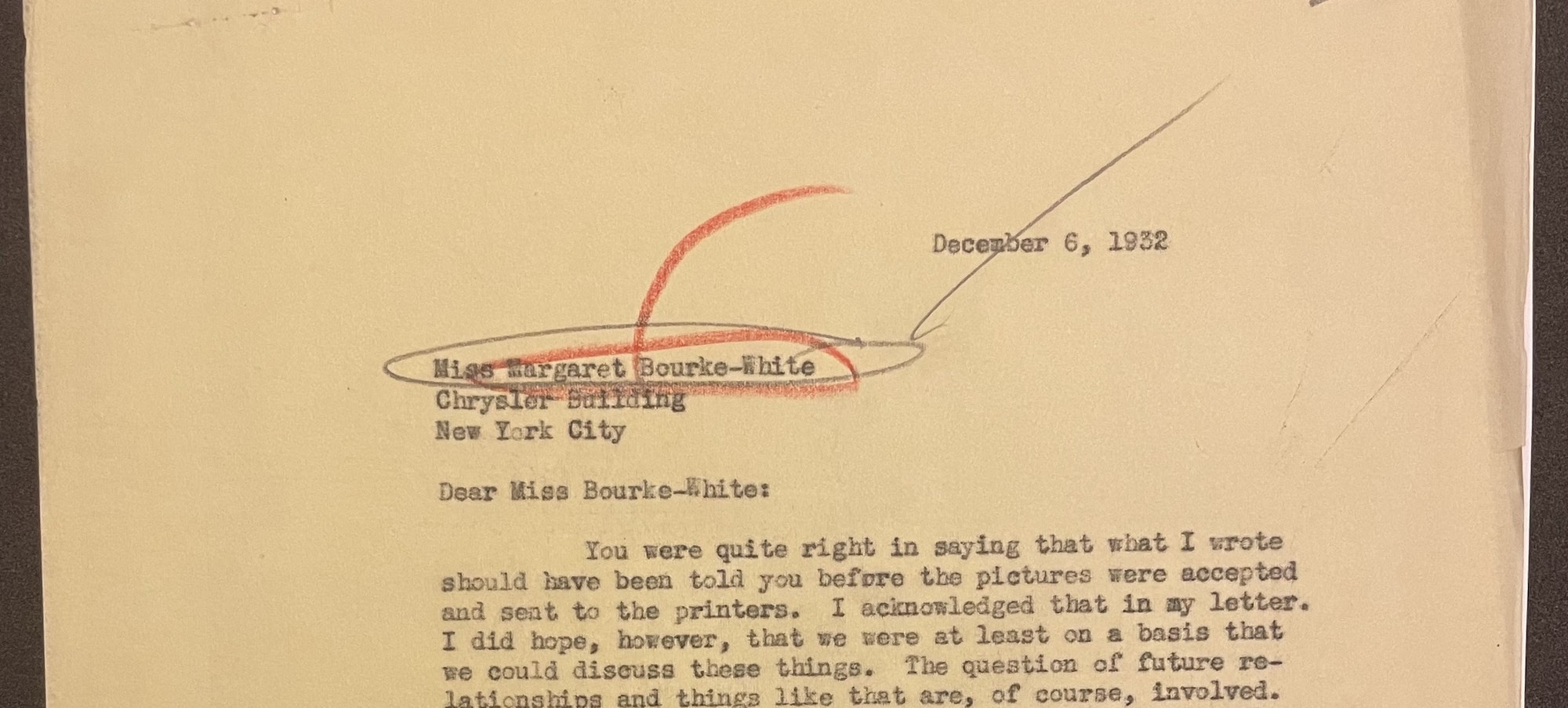

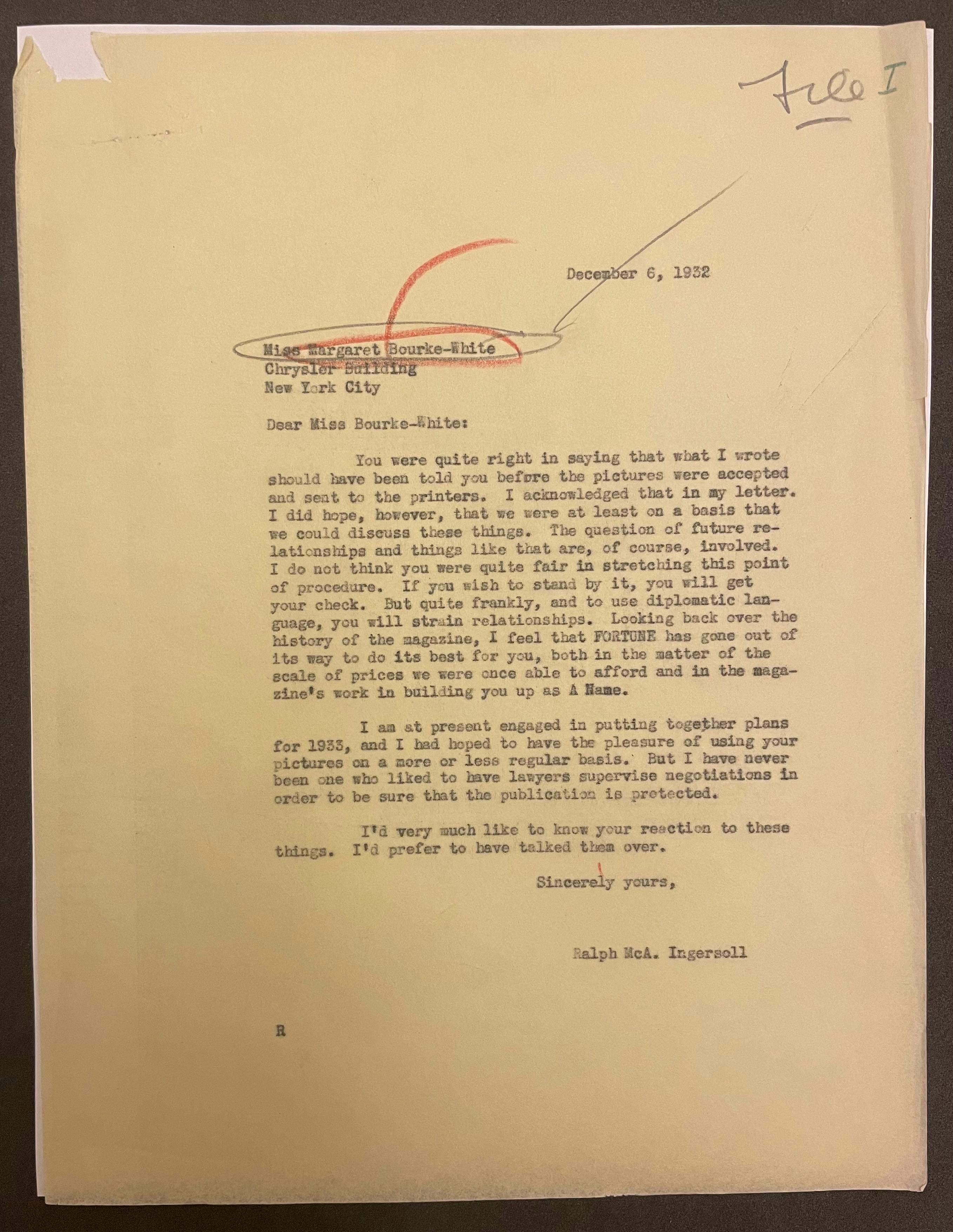

Ralph Ingersoll’s December 6, 1932 letter to Margaret Bourke-White. Time Inc. records, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New-York Historical Society.

And Ingersoll’s response, seemingly an attempt to negotiate, was accompanied by a veiled threat to use fewer of her pictures in the future, if his terms were not accepted:

“If you wish to stand by it, you will get your check. But quite frankly, and to use diplomatic language, you will strain relationships… I am at present engaged in putting together plans for 1933, and I had hoped to have the pleasure of using your pictures on a more or less regular basis…”

Bourke-White didn’t let it slide. Her final word on the matter?

“I shall be very glad to settle this and allied questions without “seconds” and preferably with cocktails at two or three paces.”

Margaret Bourke-White’s December 9, 1932 letter to Ralph Ingersoll. Time Inc. records, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New-York Historical Society.

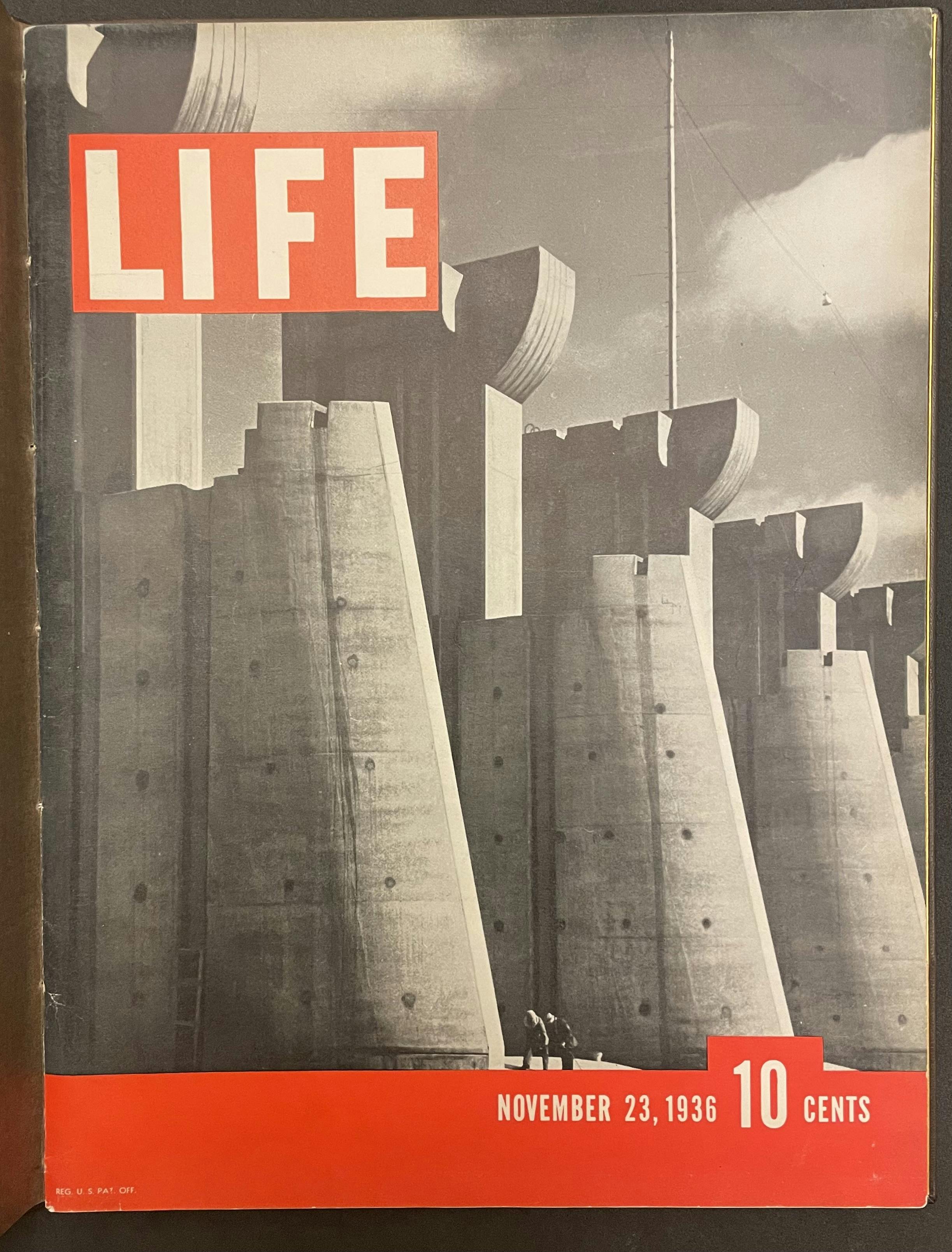

Negotiations were evidently resolved peaceably as several years later, Bourke-White’s photograph of the Fort Peck Dam in Montana appeared on the cover of the first issue of another publication, LIFE, on November 23, 1936.

First issue of LIFE magazine, November 23, 1936. Time Inc. records, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New-York Historical Society.

For Margaret Bourke-White, ultimately, her job was to ensure that great moments were not left to disintegrate in time:

“A picture is a perishable moment. It is important. If it is a great picture at a great moment, it is a part of history and cannot be allowed to escape. And it is so often now-or-never that when the great moment occurs, I could kill anyone who tries to interrupt me when I am recording it.”

The Time Inc. records are part of the manuscript and archival collections held by the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library at the New-York Historical Society. To learn more about the Library’s holdings and to plan a visit, please visit the website.

Grace Wagner is a Reference Librarian at the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library at the New-York Historical Society.