On July 18, 1862, milliner’s apprentice Philip Hamilton Hill gave word that he enlisted in the Union Army. His boss, a Jewish shop owner named Jacob Bamberg, promised his job would be waiting when (or if) he returned. The next day Philip’s father, in town from Albany, visited the Manhattan shop, taking in the news from his 23-year-old son. His father did not object, reassuring him that this was the right path.

Philip Hamilton Hill joined the 7th Regiment of the New York National Guard in 1862.

"The Departure Of The 7th Regiment To The War, April 19, 1861" by Thomas Nast. New York State Military Museum.

Philip’s decision to enlist in the army during wartime surely was not an easy one. Luckily, for historians, the New-York Historical Society holds three volumes of Philip’s diaries covering the years from 1855 to 1865. Unlike other Civil War-era New York diarists, Philip was neither a literary figure nor an elite socialite. Instead, he documents over the course of a decade his experiences as an ambitious apprentice, volunteer soldier, and young man seeking love and adventure in New York.

In the leadup to war, Philip’s main concern was Emma Chatterton. Philip recorded his evenings with Emma meticulously in his diary throughout 1859 and 1860, paying little attention to the disintegrating national political climate around him. Besides, he had another battle to contend with: Emma’s regular visits from Frank Carleton. As the city’s political classes reeled over John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in October 1859, Philip’s campaign came to a climax, when Emma’s family hosted both suitors. “Emma wasn’t even civil to [Frank], but conversed with me the whole time. I am positive that Emma loves me,” wrote Philip. That day, the 20-year-old debated growing whiskers.

Philip’s diaries also reference bygone courting customs such as philopena gifting, a flirtation game in which the first person to shout “philopena” was owed a gift from the loser. It guaranteed another meeting, so Philip didn’t mind losing. On St. Valentine’s Day in 1860, New Yorkers clamored for deliveries on the city’s busiest mail day. A giddy Philip sent Emma a “sentimental” card (as opposed to a simple comic note).

Two days later, Frank Carleton approached Philip while he shoveled snow. The meeting had the potential to turn unfriendly: Philip had, after all, won Emma’s heart. To Philip’s surprise, Frank shook hands and inquired of Emma’s family. “He did not seem at all jeallous [sic] that I had ‘cut him out,’ but talked to me as though we were old acquaintances,” wrote Philip.

Philip told few people about the courtship, either out of Victorian discretion or fear of possible rejection in public. Philip even wrote about Emma in special codes—which one of his descendants later deciphered in annotated transcripts that were saved with his diaries—but the secret of his courtship got out. “Don’t you prefer the name of Emma?” asked a relative of Jacob Bamberg’s, who fully intended to embarrass him at the dinner table one afternoon.

During their courtship, Philip gifted Emma a ring, an accordion, and a “thirty spring hoop skirt,” but, after some months, he began running out of conversation. His awkwardness was perhaps a side effect of regimented gender separation in Victorian-age New York. The two grew apart. On one evening she refused to sing for him. Then, she declined to attend Easter service with him. By spring 1860, Philip was “cut out,” and the cut ran deep. Philip later spotted Emma with his own cousin. Feeling dejected, he wrote: “One of his arms encircled her neck and both were engaged in reading a paper which lay before them. Upon seeing me neither moved from their position.”

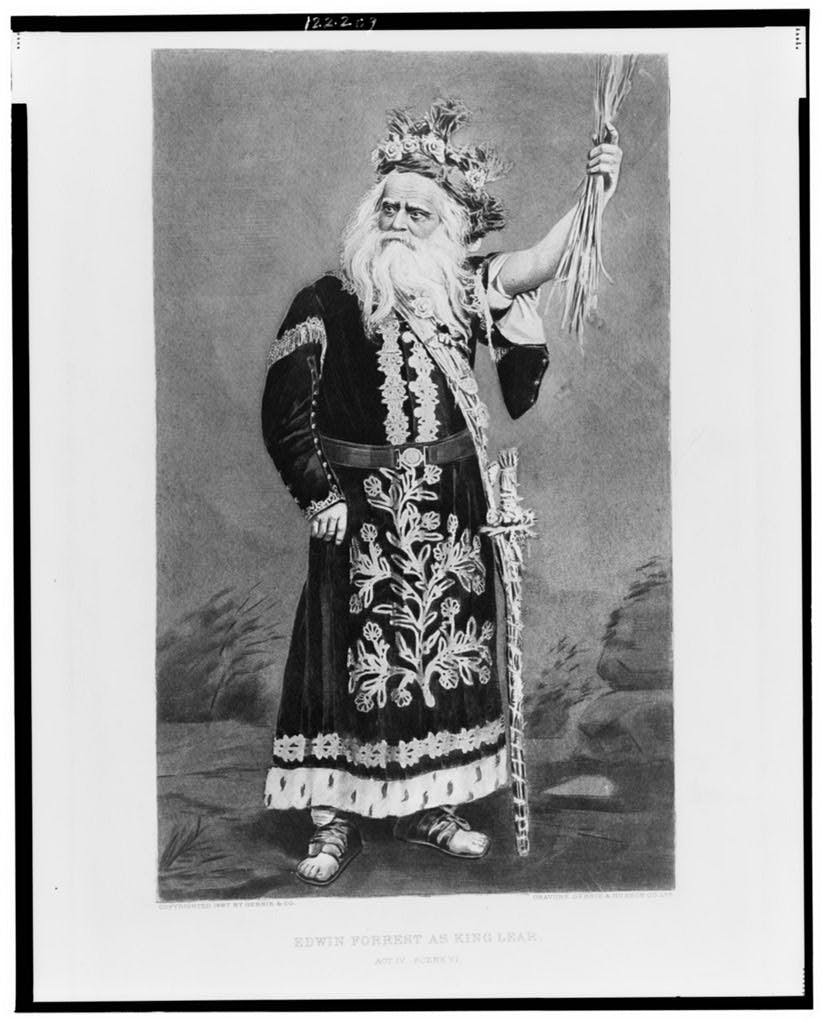

He pledged to forget her. Entertainment in New York proved an apt distraction from a broken heart. As an apprentice, Philip earned $5 per week, which meant that he could afford regular trips to the theater. He went to see Edwin Forrest play Shakespeare’s King Lear in October 1860 at Niblo’s Garden. On Thanksgiving Day, he saw the other great Edwin—Edwin Booth, the brother of Lincoln’s future assassin—star in The Apostate about the Spanish Inquisition. “I had expected better,” Philip concluded. “I was not nearly as happy as I was last year, when I had Emma by my side,” he added.

Edwin Forrest as King Lear, Act IV, Scene VI.

Gebbie & Husson Co. Ltd. , ca. 1897.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

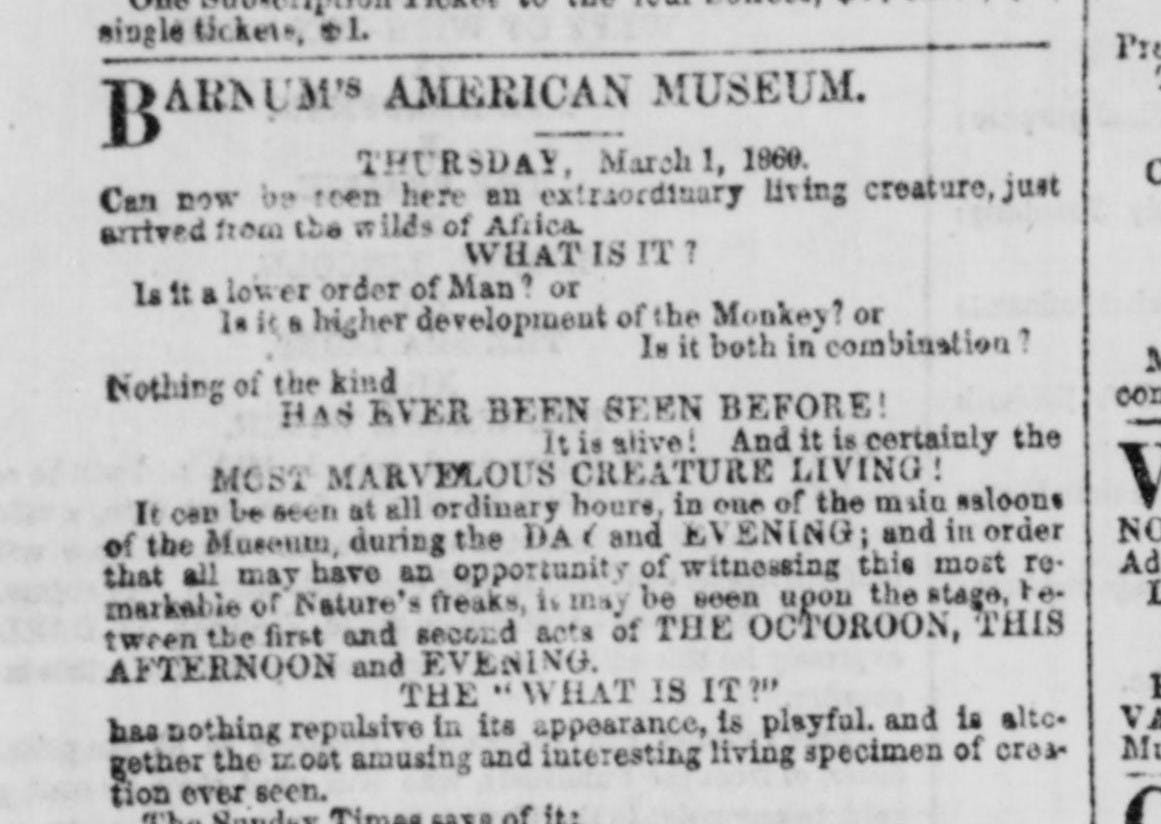

In his search for diversion and leisure, Philip attended the new “What Is It?” exhibition at P.T. Barnum’s American Museum in August 1860. One of Barnum’s most infamous exhibits, “What Is It?” presented a young Black performer as nonhuman, claiming that he was the “real link between the man and the monkey.” The exhibition opened shortly after the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and during the height of political tensions over slavery in the US. An advertisement in the New York Tribune asked spectators: “Is it a lower order of Man? or is it a higher development of the Monkey? or is it both in combination?” That Philip remarked only briefly in his diary about seeing this display reflects the degree to which institutional and societal racism pervaded in New York City at the time.

Ad for Barnum's American Museum,

New York Daily Tribune, March 1, 1860.

Library of Congress.

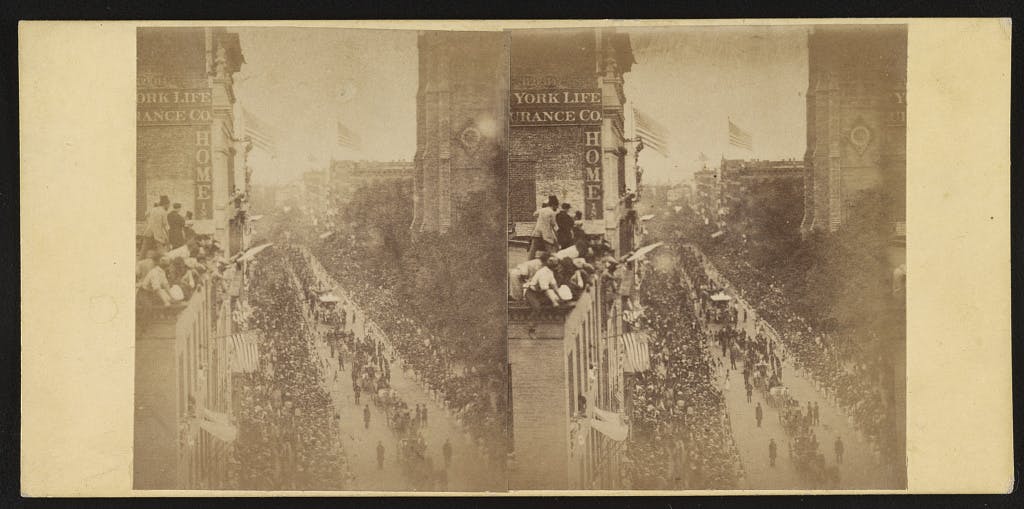

While he wrote very little about the Barnum exhibit, Philip filled his diary with details of the parade for the first official Japanese embassy to the United States in 1860. It comprised more than 70 Japanese samurai diplomats on a seven-week tour, stopping in San Francisco, Washington, DC, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and, finally, New York. In June, more than half a million New Yorkers turned out for a welcome parade, one of the biggest events in New York up to that time. Philip wrote:

"After dinner I left the store and went down to Broadway and Battery. Broadway alone was a sight to behold. One would think that all New York was in the street, for it was crowded to excess, and a person going either way had hard work to get along. The windows of the different hotels and stores presented a beautiful sight never to be forgotten. Each window was filled to the utmost with ladies and children, while the window-sills and awnings were covered with men and boys. The lamp-posts, trees, stoops, and other things of like description were seized upon by young and old."

"Reception of the Japanese Embassy, New-York, June 16, 1860."

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Amidst celebratory cannon fire, Philip darted up Broadway near Trinity Church. As the first Japanese ambassador appeared, “the crowd gave vent to their exultation in cheers and waiving of handkerchiefs,” as the delegation bowed in return. “Where is Tommy?” Philip heard people asking. It was the nickname given to the most popular and youngest (and perhaps the most attractive) member in the delegation, Tateishi Onojiro. “That’s him. There he comes,” the people on the streets shouted. “Hurrah for Japan,” shouted more voices over the band playing outside the Metropolitan Hotel, where the diplomats stayed. Philip was impressed by the marching US soldiers:

"The famed Seventh Regiment was out in all their glory, and took the shine off all the others completely. When they approached, the air rang with the cheers of the crowd, and they well deserved the applause they received for I never saw them march better."

Philip soon marched in the Seventh. In 1862, he affixed his diary with Union stickers, including an angel dressed in the US flag, avenging the attack on Fort Sumter. A Confederate devil sits atop a case of cotton, symbolizing the Southern plantation economy. No less pointedly, there is a boot to the rear end of Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

The final volume of Philip’s diary chronicles his service as a soldier during the Civil War, including the military careers of his two brothers and his short mobilization at Fort Federal Hill in Baltimore in 1862. Philip survived the war but stopped keeping a diary in 1865, around the time he married Emma Tompson. (Perhaps he did prefer the name "Emma" after all.) Philip also became business partners with his former boss Jacob Bamberg in the mid-1860s, and continued in the millinery trade until about 1890. Rather than a recounting of news headlines or his opinions on national politics, Philip’s diaries provide insights into his direct personal experiences—courting women, social interactions, leisure activities, and military service—as a young man finding his way as part of the growing commercial middle class of New York City in the mid-19th century.

Joshua K. Leon was the 2022-23 Robert David Lion Gardiner Fellow at the New-York Historical Society. He is chair of Political Science at Iona University and is working on a book called New York 1860: City on a Precipice.