Having just completed my research on the history of the land that eventually became Central Park in Before Central Park (2022), I found myself in search of a new project. It was during a chance meeting with Margi Hofer, Senior Vice President and Museum Director at the New-York Historical Society, that I pondered whether anyone had studied the property's ownership before New-York Historical acquired its location on Central Park West. To my surprise, Margi informed me that no such study had been done. I seized the opportunity to delve into this research. During my previous project, the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library proved to be an invaluable resource to me, and this endeavor felt like a way to contribute to the history of the place that had been so important to it. Additionally, the proximity of the building to Central Park suggested a shared history that piqued my curiosity. In a series of three blog posts, I’ll share what came before the grand Museum and Library that are now at 170 Central Park West.

*****

The earliest records related to the site that is now home to the New-York Historical Society date to the middle of the 17th century. In 1667, just three years after the English took over New Amsterdam from Dutch rule, Governor Richard Nicolls granted the first and largest royal concession of private land to a consortium of five wealthy investors, comprising three Dutchmen, a Frenchman, and an Englishman. This original land tract extended along the North (Hudson) River, roughly from 34th Street to 120th Street and eastward to Seventh Avenue. It spanned some 1,300 acres and encompassed a significant portion of what later became the west side of Central Park. On September 12, 1667, the five investors received a patent for the land above 57th Street divided into ten 100-acre lots—each lot bordered the Hudson and extended inland for about four-fifths of a mile. Lot number seven—the future home of the New-York Historical Society—eventually became the property of the Englishman Thomas Hall.

Thomas Hall's journey to wealthy landowner was quite remarkable. He arrived in Virginia as an indentured servant to George Holmes in 1635. In 1639, Hall and Holmes were part of a group of Englishmen who attempted to establish an unauthorized colony within Dutch territory along the Delaware River. They were quickly captured by the Dutch and imprisoned in New Amsterdam. Hall chose to settle there after his release and began to adopt Dutch customs and culture and learned the Dutch language. In the same year, the Dutch granted Hall and Holmes land for a tobacco bouwerie (farm) on the east side near what is now the United Nations. However, farming didn't align with Hall's adventurous spirit: instead, he chose the risks and rewards of Manhattan real estate. His success in this venture made him a wealthy and influential leader within the Dutch colonial government. Notably, he was among the 93 New Amsterdam citizens who signed the articles of surrender to the English in 1664, an ironic twist given his English heritage.

Hall’s landed estate was vast, and he died a much richer man than when he had settled in New Amsterdam. His 1669 will (now in the Manuscript Collection of the New-York Historical Society) left many of his real estate holdings to two cousins and his widow, Anna Medford Hall, as “his sole and universal heir.” Anna Hall gradually sold off her late husband's properties across Manhattan. On September 24, 1670, Hall sold her Turtle Bay east side dwelling, orchard, mill, and brewery to William Beekman, which was laid out in the 1860s as Beekman Place. Between 1685 and 1686, Anna Hall sold 100 acres of west side farmland from lot number seven, previously purchased by Thomas Hall, to a free Black man named Anthony John Evertse. Historians don't know much about the details of Evertse's life, but most likely, Evertse was formerly enslaved in New York. It is possible that he saved enough money from work performed outside of his enslavement to purchase the property after gaining his freedom. In 17th-century colonial British North America, it was quite rare for a free Black man to own such a large tract of valuable farmland—a testament to the complex, remarkable, and diverse histories of colonial New York City. Evertse owned this farm for less than two years before he sold it to Dutchman Adrian Van Schaick in March 1697.

Plate 84B-d (detail below), shows original property of the five investors and the Tunis Somarindyck farm including Block 1129, which is the site of the New-York Historical Society.

I. N. Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909, volume 6, n.p.

In 1701, Van Schaick’s widow, Rebecca Van Schaick, sold the property to Cornelius Dyckman, who divided it between his two sons. The younger son, Cornelius Jr., inherited the portion that would eventually accommodate the New-York Historical Society. In 1745, Cornelius Jr. gave the estate to his granddaughter, Cornelia, as a wedding present upon her marriage to Teunis Somarindyck. Their farm extended from the Hudson River east to Seventh Avenue, and north from 73rd to 77th Streets. Topographic maps indicate that the block between 76th and 77th Street was suitable for cultivation, in contrast to much of Somarindyck's property to the west, which had significant rock outcrops and few natural waterways. In his deed, Somarindyck described himself as a farmer. Like many New Yorkers who owned extensive farmland and large homes, Tunis Somarindyck enslaved six people, who worked on the property that would later be the site of the New-York Historical Society, as well as significant areas within Central Park, including Strawberry Fields, Hernshead, and the western shoreline of the lake.

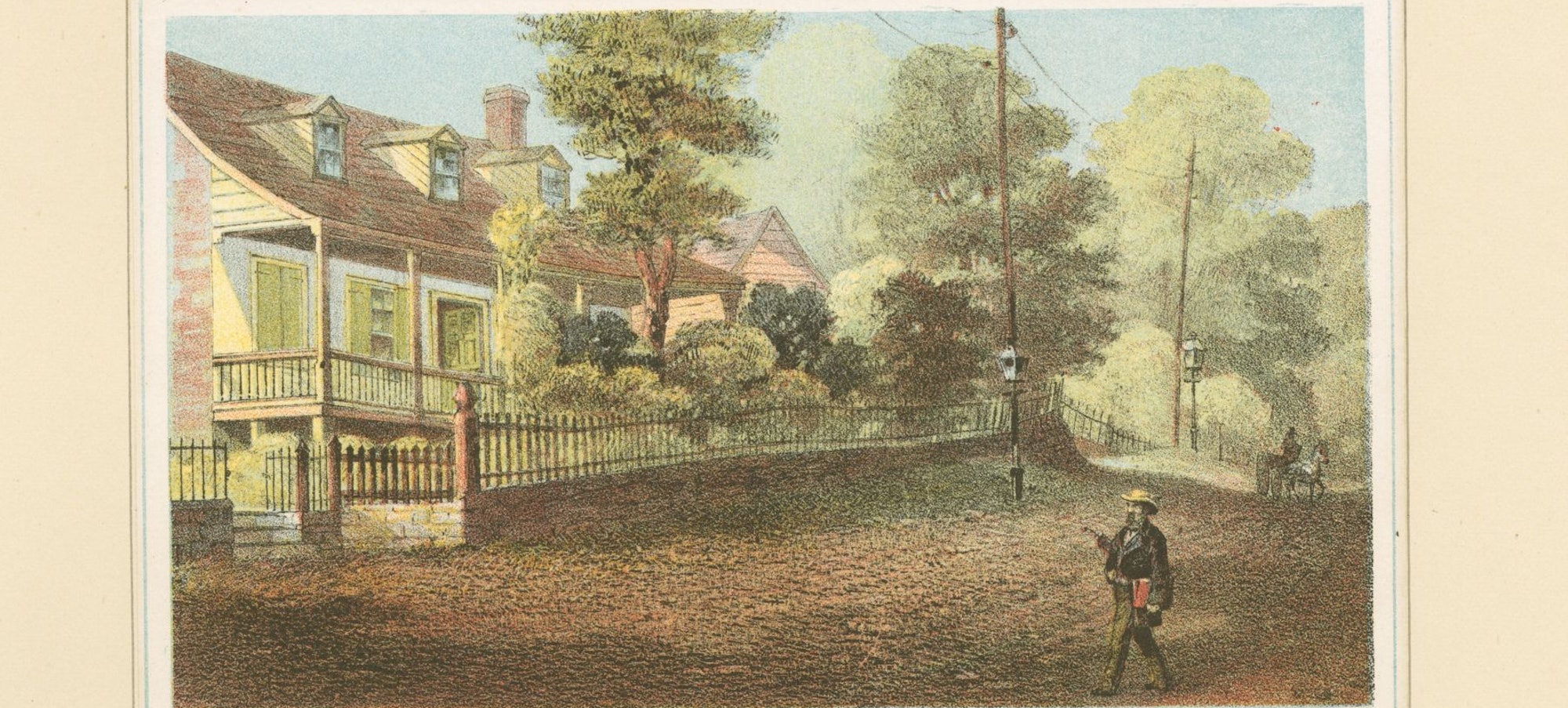

An etching of the Somerindyke House in Bloomingdale, New York City in the summer of 1868 by Eliza Greatorex. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library.

The Somarindyck house stood as a west-side landmark for over a century, located near the northwest corner of 75th Street and the Bloomingdale Road (now Broadway). They built another home on the corner of 77th Street, which later became known as “Woodlawn” as the property of the notorious New York mayor Fernando Wood in the 19th century. During the Revolutionary War, as Hessian soldiers approached the house, the Somarindyck family hid behind a trap door in the large garret and the house was made to appear hastily abandoned. The Hessian soldier then occupied it for some weeks, and according to one account, neighbors passed the family food and water via a pulley bucket through a small window. Eventually, Somerindyck repaired the damage done to his home during the war and restored it to its former comfort and elegance. Some years later, the exiled French King Louis-Philippe and his younger brothers likely stayed at the Somerindyck estate in about 1796, where according to one newspaper, Louis-Philippe taught various subjects to paying students.

"Somerindyke estate on Bloomingdale Road, near 75th St" (top) and "Interior of Somerindyke House, in which Louis Philippe (late king of the French) taught school" (bottom). Lithograph published by Sarony, Major, and Knapp, 1863. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library.

After Tunis Somarindyck's death, his son Richard inherited the Bloomingdale farm in 1796. His will instructed Richard to sell most of the cattle and horses, leaving his wife Cornelia with the farming equipment and two enslaved individuals. Importantly, Tunis also directed his executors to sell "my black woman Jane, and all her children, that are not disposed of by the time of my decease." These decisions reflect Tunis's recognition of Manhattan's transition from an agrarian society to an urban real estate market that no longer relied on enslaved farm labor at the turn of the 19th century.

Cadastral map of the area later bounded by 56th and 78th Streets, 7th Avenue or Central Park, and the Hudson River, Manhattan, New York, N.Y. New-York Historical Society.

Richard Somarindyck wasted no time in divesting himself. Beginning just months after his father’s death, he sold the property that was the original lot number seven to Joseph Covacheche in April 1797. It then changed hands among real estate investors six times over the course of the next 13 years: to Joaquim Monteiro (July 1797); to Jones, Jones & Clinch (September 1801); to Thomas Cadle (March 1804); to John Mason and Ichabod Prall (January 1811); and finally, the eastern half of the block between 76th and 77th Streets to David Wagstaff (April 1811).

David Wagstaff, a prosperous grocer, importer, farmer, and civic leader, owned extensive tracts of prime Manhattan real estate. He invested in this property for a variety of long-term purposes, including for use as farmland and to generate income from rental properties, intending to pass the land and its buildings to his descendants.

Map of the Wagstaff property deeded to his children. New-York Historical Society original buildings planning & construction records, Series III. Central Park West Construction: Central Portion, 1880-1918, Abstract of the Title of N-YHS to Ten Lots of Land in the City of New York, August 19, 1891, RG 3 Box 5.

Wagstaff's estate played a major role in New York real estate history in the mid- to late-19th centuries. Portions of his uptown property eventually became all or part of New York’s most celebrated institutions: Central Park, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, and the New-York Historical Society.

When David Wagstaff died in 1824, four of his children inherited the land that would become the New-York Historical Society. They used the property as an investment in much the same way their father had done, but eventually their children (David Wagstaff's grandchildren) sold it to many fascinating new owners.

Read Part II to find out more!

Sara Cedar Miller is the historian emerita of the Central Park Conservancy, which she first joined as a photographer in 1984. Her most recent book is Before Central Park (2022).