On October 7, 1943, Lincoln Kirstein wrote New-York Historical Society Librarian Dorothy Barck a letter. But this wasn’t the Lincoln Kirstein that New York would come to know—co-founder and director of the New York City Ballet, prolific author, patron of the arts, recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This was 36-year-old Private Lincoln Kirstein of the US Army, and he had a question about art.

Letter from Dorothy Barck to Lincoln Kirstein dated October 15, 1943. New-York Historical Society Librarian Dorothy C. Barck records. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library. New-York Historical Society.

Kirstein was stationed at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, where he’d been sent to serve as a combat engineer after completing basic training during World War II. Feeling worn down by the physically demanding and intellectually stagnant nature of his work at the base, Kirstein was seized with the idea of studying soldier art, what he would later describe to Barck as “the pictorial record of our wars, by the soldiers who fought in them.” He funneled his redoubtable energy into the task and received permission from his superiors first to document the art of Fort Belvoir, and then to expand the scope of his project to the art of American soldiers writ large. In the course of this work, he reached out to experts at institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Library of Congress, the National Gallery, and the New-York Historical Society.

Lincoln Kirstein in Normandy, August 1944, starting "Rhymes of a Pfc," no. 99. Lincoln Kirstein Family Photo Albums, Volume 3. New York Public Library.

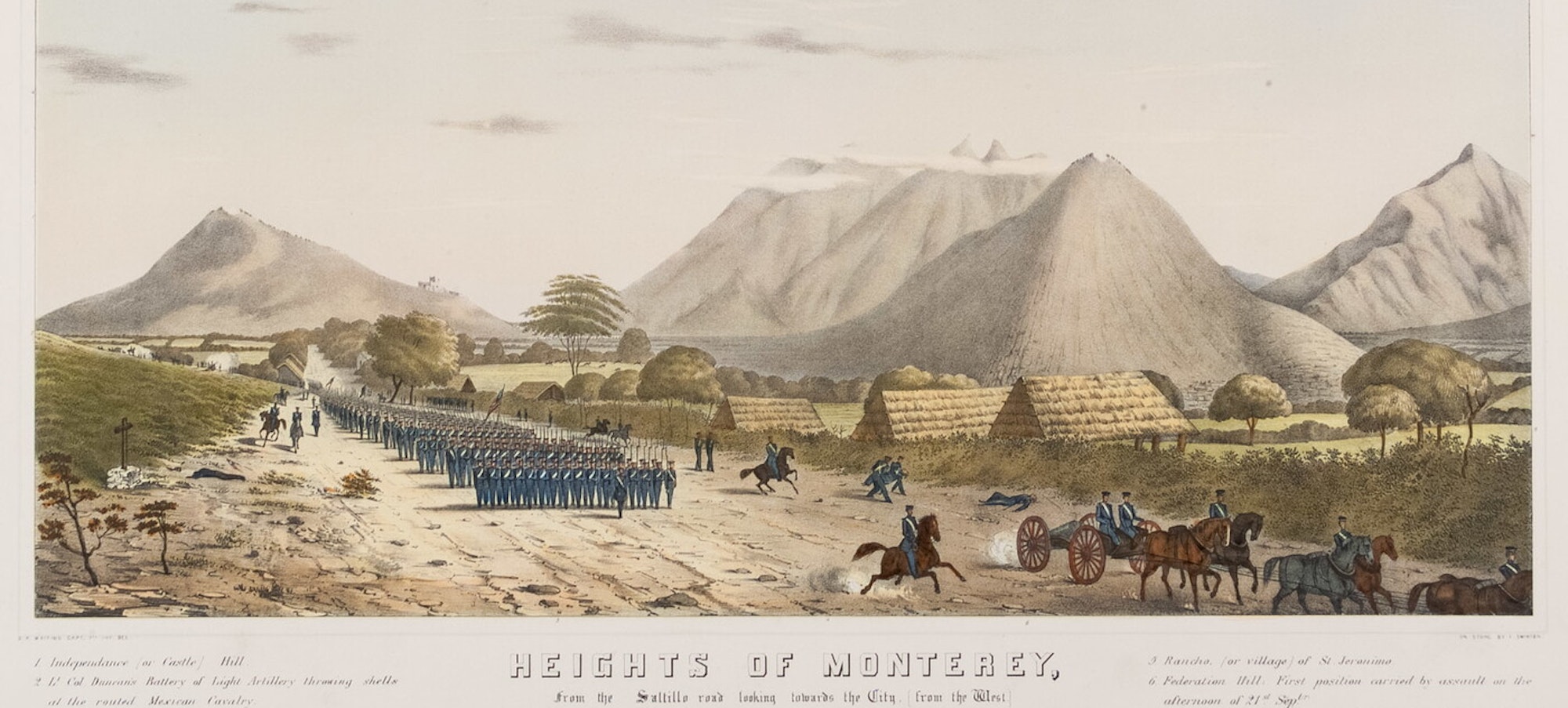

In his initial request, Kirstein indicated an interest in “drawings by soldiers during earlier wars.” Barck pointed him to published sources and relevant repositories—as any good reference librarian would—and then suggested the five lithographs of Captain Daniel Powers Whiting’s army portfolio held by New-York Historical’s library. Captain Whiting was an officer in the 7th Regiment, whose illustrations depict the capture of the city of Monterrey by US troops during the Mexican-American War. Before the war, Whiting received training as a topographical artist at West Point, which doubtless influenced his artistic skill and the accuracy of his illustrations.

Heights of Monterey, from the Saltillo Road Looking Towards the City. Army Portfolio of Captain Daniel Powers Whiting. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas.

Whiting’s original illustrations were transferred to lithographic stones by a series of lithographers and printed by the G. & W. Endicott firm in New York. Lithography is a form of image transfer and reproduction that relies on the repelling qualities of water and oil, like a puddle in a driveway. The lithographer sketches their illustration on a flat lithography stone, using an oil-based pencil. After the stone is treated with an etching mixture that makes the blank spaces more water-absorbent, it is dampened and covered with an oil-based ink. The ink adheres only to the illustrated lines, and is then transferred to paper pressed against the stone. (As with many book production and printmaking processes, it can be easier to follow this process by watching it in action.) Because it doesn’t rely on the carving that characterizes woodblock printing or copperplate engraving, lithography can produce a more natural line, though its final print often has a flatter appearance. And because lithographs both demonstrate artistic skill and are produced in sets, they are often held by art museums and research libraries alike. At New-York Historical, the Whiting lithographs are part of the library’s Prints, Photographs and Architectural Collections, within the Subject file collection (PR 68, box 22). According to the account of Whiting’s family, no more than 24 sets of the portfolio were made; an extant complete set is a rarity.

Letter from Lincoln Kirstein to Dorothy Barck dated October 19, 1943, with Barck’s handwritten notes. New-York Historical Society Librarian Dorothy C. Barck records. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library. New-York Historical Society.

Though initially interested in all five, Kirstein narrowed his focus—presumably when faced with the cost of their reproduction—to two lithographs: Camp of the Army of Occupation and Heights of Monterey from the Saltillo Road. Barck provided these as photostatic negatives, or photostats, a common reproduction method at the time, where a camera captured an image and exposed it directly onto specially prepared paper. Because it was printed in negative, darker features of the original would be printed light, and vice versa. The result was a final product that was essential for transmitting information in a pre-digital day but that must have left the art connoisseur feeling dissatisfied. The Carter Museum has digitized their copy of Whiting’s portfolio in high-resolution, color images that would have been a dream to Kirstein.

What Kirstein did with these images is not (yet) known. He did go on to display his “battle art” in exhibitions at the National Gallery, the Library of Congress, and MoMA. The Library of Congress exhibition featured lithographs, but only the National Gallery iteration received a catalog. Perhaps, after seeing the photostats that Barck provided, Kirstein included one of the Whiting lithographs held by the Library of Congress in their iteration of the exhibition.

As his biographer Martin Duberman details, Kirstein had grand plans for his art project, including creating an American museum dedicated to soldiers’ art. But his wartime activities would soon switch gears as, with the help of his well-connected art world friends, Kirstein was reassigned to the US Arts and Monuments Commission, more colloquially known as the Monuments Men. But that’s another story.

Meredith Mann is Curator of Manuscripts and Archival Collections at the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library at the New-York Historical Society.

The Librarian Dorothy C. Barck records, part of the New-York Historical Society’s Institutional Archives, are one of the thousands of manuscript and archival collections held by the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library at the New-York Historical Society. For over two hundred years, the Library has—through its manuscripts, books, maps, newspapers, photographs, architectural drawings, and prints—richly documented the history of New York and its wider national and global surroundings. These unparalleled collections are available to researchers, students, and all those curious about our shared past and present. To learn more about the Library’s holdings and fellowship opportunities, and to plan a visit, visit its website.