Welcome back to the Women at the Center discussion about the HBO series The Gilded Age! The first two episodes of season two have given us plenty to discuss, from the politics behind some of the feathery fashion to a deep dive into the great Opera Wars. Read our conversation about the first two episodes in the season below, and stay tuned for more.

Valerie Paley (Founding Director, Center for Women's History and Sue Ann Weinberg Director of the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library): The first episodes of this season reminded me of how this show plays fast and loose with the way that people would have interacted across race in this time period. The audience just has to suspend their disbelief and accept that Marian– who’s a white, upper-class debutante– is besties with Peggy– a middle-class Black journalist who works for Marian’s aunts. Even if a friendship between the two was plausible, it’s hard to believe that they could hang out at a restaurant together, and it would be no big deal to the rest of the customers.

Salonee Bhaman (Mellon Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow in Women's and Public History): We’re also seeing some acknowledgment of the different social worlds in the opening scenes of this season, which take place at different churches.

VP: Right, there are three churches—a Black church, an upper-class white church, and the working-class church. Right off the bat, I wanted to mention the new rector whose accent struck me as out of place. I mean, we get that he’s Italian by way of France—but his accent is so working-class Italian-ish Boston. You’d expect him to sound more faux-British “Episcopal,” or at the very least, like a Kennedy.

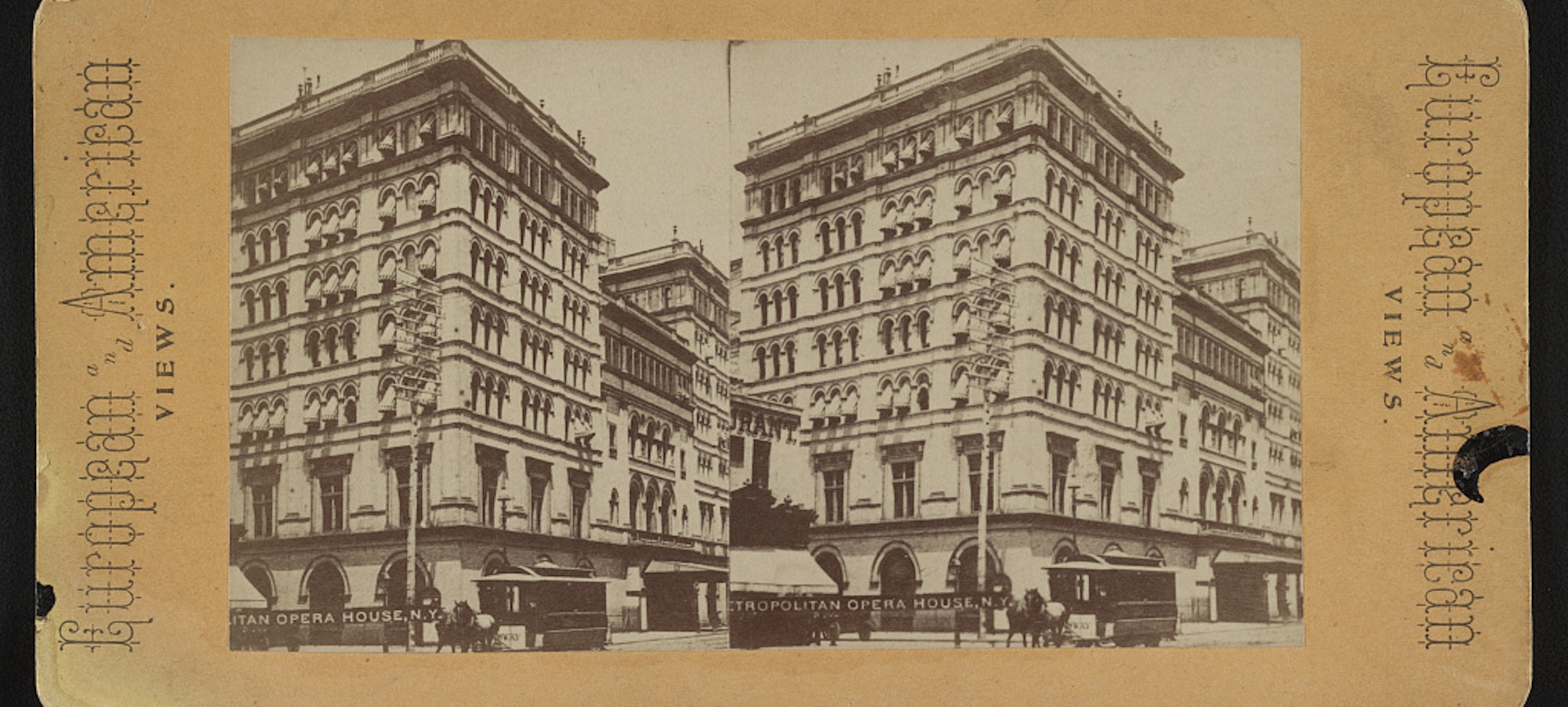

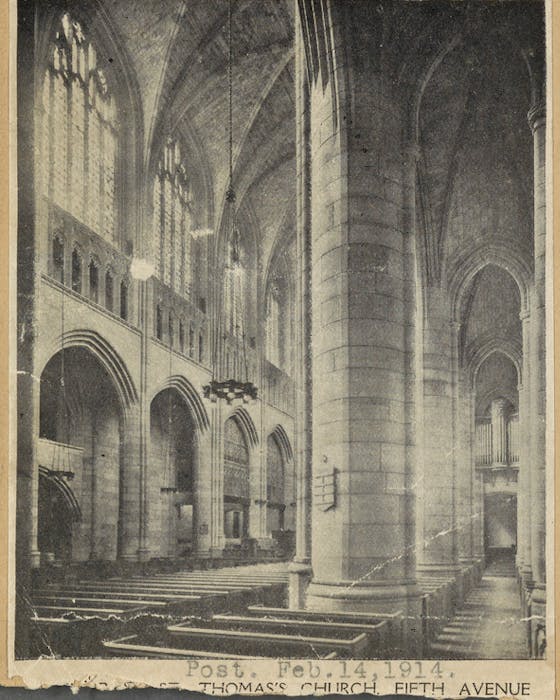

SB: I wonder if he’s going to be a bigger part of the story. I noticed that they got to the church on foot, suggesting that it was St. Thomas's, which was on 53rd and 5th. The old guard might have been attending Easter services at Grace Church, much farther downtown.

VP: The sexton at Grace Church at the time, Isaac Brown, was also quite a large social influence—an arbiter, in fact, like Ward McAllister. There’s a lot more to “church politics” rather than just religious worship, and it’ll be interesting to see how this all plays out in this season.

"St. Thomas's church, Fifth avenue," courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections. The version of the church pictured here was rebuilt after a fire, in 1905.

SB: The outfits at church are pretty spectacular in these episodes. I kept looking at the bustles to see if they were changing in size, as you all discussed last season. I couldn’t really discern too much of a shift, they seemed all over the place.

VP: Well, there’s definitely no subtlety to the prints that they’re wearing. They’re beautiful—they’re just too much. I don’t think they’re realistic to the period.

Keren Ben-Horin (Curatorial Scholar in Women's History): I felt that out of everyone, Marian’s clothes—the colors, the fabrics—may be the closest to what someone of that class, at that age, would have worn. The contrast that they draw in terms of how they’re building characters with color is fascinating, actually. Marian’s older relatives wear brown, dark greens, and wine colors. It’s very heavy. And Marian is always in these yellows and pastel colors.

VP: I was reminded of the Ascot scene in My Fair Lady: everything’s bold and overscale, as opposed to the subtle textures that might have been more accurate.

KBH: Or even these large ribbons that are going over and through the bodices, and pleats coming from every which way. Another costuming note that seems very different from season one are the hats, which now have a lot of flowers, feathers, or even sometimes actual birds. It reminded me of some of the silk flowers that we have up in the gallery in our new exhibition Women’s Work to feature the women who made them. What a distinction the women who wore those accessories and the very poor people who produced them. I was also reminded of the wild animal trade during that time period. There were whole species of birds that went extinct to make hats like that.

Jeanne Gutierrez (Curatorial Scholar in Women's History): Right—that was actually a whole New-York Historical exhibition of hats paired with Audubon’s drawings of birds. It was called Feathers: Fashion and the Fight for Wildlife. The rapid destruction of so many species actually kicked off an environmental movement that eventually successfully lobbied for protections like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. It makes sense that the hats would be so elaborate, because New York at the time was at the center of the feather trade.

KBH: At one point, someone is wearing a hat with two birds growing together, with the actual body of the bird on the hat. It was really eye-catching, and also something reflecting fashion magazines from that period.

SB: Ward McCallister says “No tiaras! I like to see feathers by the seaside!” or something like that when the gang is going to Newport for part of the season.

Gilded Age actor Carrie Coon as Bertha Russell in an elaborate bird feathered hat. Image courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment.

Actress and Singer Lillian Russell wearing a monacle and feather hat for a portrait. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

Caitlin O’Keefe (Mellon Foundation Pre-Doctoral Awardee in Women's History and Public History): I was actually wondering—is that an opera thing? The tiaras? We haven’t even discussed what seems like it’ll be a major plot point throughout the season: opera!

VP: Yes! The tiaras are actually a great example of how fashion, class, and opera intersect in the American realm, because in the United States, monied women were looking for ways to evoke royalty. In Europe, you go to the opera and you wear your tiara because you’re a princess. And you’re sitting in a particular box because that’s the state box for so-and-so. If you don’t officially have that class hierarchy in American society or politics, what do you do instead? You build an opera house. And go dressed up like you’re a princess, and you sit in a particular box because you are mimicking royalty, and displaying your wealth as a marker of social status.

KBH : You’re putting yourself on display in a way.

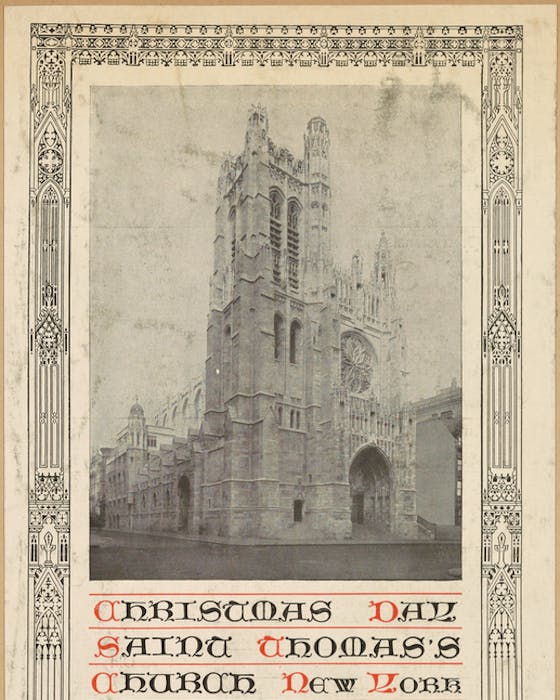

VP: Exactly. I wrote my dissertation on the creation of the Metropolitan Opera and other Gilded Age cultural boards, and I think the show’s portrayal of opera culture feels fairly authentic. They got a lot of the story right: the old guard, what we might call Knickerbocker Society, were on one side. They were Academy of Music people—that's who Edith Wharton was writing about in The Age of Innocence. These people were born into or came to social prominence in New York City earlier in the 19th century, and by the Gilded Age, were not as rich as the exorbitantly wealthy Vanderbilt clan, who arrived on the scene later in the 19th century—the kind of “new money” represented by the Russells, who did not have social clout. At least initially. And, of course, the new people who were kept out of the Academy of Music were financially able to create their own opera house if a box at the Academy didn’t materialize.

Both theaters are rooted in conspicuous consumption—people go to the opera to watch what everyone's doing in the boxes and what everyone’s wearing. They're not really watching the opera. In that regard, the Metropolitan Opera people didn't really care about the opera performance much either. What they cared about was the opera house governed by the Metropolitan Opera Real Estate Company, which was a totally different trustee group from the Opera board, which handled the performing company that sang. Two completely different boards, two totally different entities. The Vanderbilts—the Vanderbilt women, really—cared about building an opera house, which they leaned on their husbands to do. The big questions were more like, “how many boxes are there going to be, so I can put on my tiara and sit where I can show myself off?” And it was Vanderbilt money that did it. This whole idea that Bertha is the chair of the fundraising committee is a joke because it was really all a bunch of very rich men who were ponying up $10,000 or more a piece—which was a lot of money in the 1880s—to build this giant space.

SB: And did they operate at a loss at that time?

VP: Yes. Otto Kahn, an uber-wealthy financier and cultural sophisticate, quietly shored up the finances for operations for decades even as he was not given a box until the 1910s because he was Jewish. Luckily for the Met, he cared more about the musical performance than where he sat in the theater. It wasn’t until the Great Depression that the two leadership entities—and more importantly, Kahn—couldn't sustain that arrangement anymore. The Opera Company (chaired by Kahn) and the Real Estate Company (represented by the heirs of the original box owner-builders of the opera house) had to merge so that the whole enterprise wouldn’t go under. The importance of the opera in the end was really more about the structural aspects of going to the opera as opposed to the music itself—so The Gilded Age kind of got that wrong. But I still think that they got the spirit of it right.

KBH: You know, it now occurs to me that for a show that takes place in New York they hardly talk about real estate, which probably in reality they were obsessed about.

VP: It’s how the Astors made their money!

KBH: I wanted to ask you: what do you think about the way they portray the relationship between Bertha and her husband?

VP: Like they're Lord and Lady Macbeth?

KBH: Well, I mean in the way it seems like she's like pulling all the strings and he just goes along and that's her part of this empire.

VP: Actually, that feels pretty accurate. And my problem really is just...the acting is sometimes challenging. Or is it the dialogue? A little bit of both? There's something so stilted about it that feels cringey. And then when they kiss, it's—yuck!—fast forward! I find some of the actors are so awkward to watch in a romantic situation. Anyway, to answer your question, yes, indeed, men designated a kind of soft power to their wives through these social means. Sometimes it even becomes hard power. The men are making the money, and the women are in charge of putting it on display in a particular way.

SB: That idea that they’re performing in a way that makes them kind of illegible or repulsive as romantic actors strikes me as actually kind of...very Victorian in a way.

Anna Danziger Halperin (Associate Director, Center for Women's History): In terms of the opera wars, is Bertha Russell supposed to be somebody here? Was there a woman who was like her?

VP: She’s sort of Alva Vanderbilt. The Russells could be a few different members of the Vanderbilt family. However, it was really the men of the Vanderbilt clan who were putting together the money for the new opera, really for their wives and daughters. The Vanderbilt women certainly wanted to go to the opera and see and be seen, but it would have been Vanderbilt men doing the fundraising. The series mentions Mrs. Vanderbilt sometimes, but they kind of gloss over the name. The fact is, Mrs. Astor was the doyenne and the Vanderbilts were the nouveaux that they didn't really want to hang with. Ultimately, what happens—and probably happens later in the show, too—is that there’s something so titillating and extraordinary about what they’re building at the Metropolitan Opera that Mrs. Astor does in fact get a box. The opening night is the same night as the Academy of Music’s, everyone’s watching the two different factions. In reality, Mrs. Astor didn't go to either one. I think she said, “I was in the country.” Which she never would have really done!

SB: And do you think it's the social spectacle that's what's titillating about it?

VP: Absolutely. It was sort of like going to the hottest thing in town or the fanciest new restaurant and getting a reservation there.

Diagram of boxes at the Metropolitan Opera House published in the New York Daily Tribune, May 27 1883. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

SB: There’s also mention of the “new museum” on 5th Avenue. I assume that’s the Met. Is it the same group of people involved in founding that?

VP: A lot of the same men who founded the Metropolitan Opera House were part of the cadre of men that started the Metropolitan Museum, although the museum included a wider swath of society: there were more old money people involved in the founding of the museum, along with artists and intellectuals. But that's a whole different chapter of my dissertation!

KBH : It’s really interesting how these people are so invested in building these new cultural institutions as an expression of their class and money.

VP: Yes, because in Europe, museums and culture were and are state funded. So this was something that these rich New Yorkers could do with their money to not only establish the template for a cultural infrastructure for New York and the nation, but also give themselves something to do that had a kind of power that approximated royalty.

There’s one other thing I wanted to say. Nathan Lane, who is the actor who plays Ward McAllister, is hilarious. The character is based on a real person, who was Mrs. Astor's “major domo”—the one who famously said there were only 400 people in New York society because that was the number that could fit in her ballroom. I don't think he necessarily would have been flitting around from seeing the nouveau riche Mrs. Russell to seeing Mrs. Astor. He was snobbier than that, and a bit of a gatekeeper in his own right. Mrs. Astor would certainly have disapproved if he had a serious relationship with the Vanderbilts. It makes him a more interesting character for the purposes of the show, though.

"Samuel Ward McAllister (1827–1895)" by McD, courtesy of the New-York Historical Society.

SB: Let’s switch gears to the opera performance itself.

Hope McCaffrey, (Mellon Foundation Pre-Doctoral Awardee in Women's History and Public History): Well—this is a small thing, but the preview performance was actually sung in Italian, rather than French. Faust is a French opera, based on a German play. It’s performed here in Italian though, which surprised me.

VP: Oh, she wasn’t singing in French?

HM: It caught me off guard when she started singing.

VP: I was actually thinking that it didn’t sound right. And it was only later on during World War I that any operas that were in German were retrofitted into Italian.

CO: Well, that's interesting. There’s a funny passage at the beginning of The Age of Innocence that basically describes the scene: “An unalterable and unquestioned law of the musical world required that the German text of French operas sung by Swedish artists should be translated into Italian for the clearer understanding of English-speaking audiences.” So it seems like this was done, but not without some snickering about American snobberies and sensibilities.

HM: And I actually noticed on the blog post last season, we noted that they tried to do everything like the French. So it's funny that they take a Gounod opera, written in French, and put it in Italian.

VP: That is very funny. So did they sing in Italian?

HM: It seems like that, based on The Age of Innocence.

CO: The Age of Innocence also starts with a performance from Christine Nilsson, the Swedish opera star we see in The Gilded Age. Clearly the writers have also read some Edith Wharton.

VP: If you see Scorsese's The Age of Innocence, it also begins with a performance of Faust.

"Christine Nilsson." Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

SB: Let’s take a quick step away from opera to talk about Oscar's plotline this season. He’s a queer character, and we get little snippets of what’s going on here. He seems to have gone out in the Village after Easter services and then been beaten up after essentially cruising.

VP: Yeah, this is pretty fascinating. And I guess he’s jilted by his lover—John Adams?

SB: They might still be kind of together, John Adams admonishes Oscar to stop cruising in the episode. Of course, not what they would have called it then.

KBH: Right, John wants to be out, it seems. Or wants to live a different kind of life, whereas Oscar feels like he must remain closeted. To marry.

VP: Oscar is trying to marry the Russells’ daughter, yes? And he gives her this justification, which to me feels like a more realistic depiction of marriage, actually. When she asks, “why should I marry you?” He responds essentially that he wouldn't make her unhappy.

ADH: And that he’ll give her more independence, too.

KBH: I actually think it could be a good match in some ways. Tentatively.

VP: So then Mr. Russell says no, because he wants his daughter to have a love marriage. That’s a different objection from the one his wife would presumably have had, given Oscar’s social standing. The idea of a “love marriage” wasn’t new, but it was a lower-class thing. Or at any rate, not something that Russell would have cared about one way or the other for his daughter.

KS: I also think it’s important to note that during that time period, men who had same-sex relationships didn't necessarily see themselves as inhabiting a homosexual identity. Especially when they were from the higher classes.

VP: That reminds me of an interesting connection between opera and gay culture, because later on, one of the only places where men could congregate, publicly flirt, and legally hang out like that was at the bar at one of the upper rings of the Met.

ADH: On the same topic of relationships, when Mrs. Russell was so horrified that her son was sleeping with the widow—I don’t think she would have cared, in actuality.

KBH: She's the older woman.

ADH: She’s a respectable widow, isn’t she? Wasn’t that common knowledge that this was kind of a sanctioned relationship? Upper class men can go to prostitutes, or they can sleep with widows. It just seems so sanctimonious of Bertha to think that it would hurt Larry’s reputation.

SB: Do you think that's a way for the show to signal that the Russells are not actually in sophisticated society so that they have these more pedestrian mores around marriage? Or is that too much of a reading into it?

JG: Well, I do think a “love marriage” is a very middle-class idea. I remember reading in Godey’s Lady’s Book in the 1840s, they are talking about companionship and marriage as an ideal situation.

Godey's Lady's Book, January 1884. Image courtesy of The Internet Archive.

VP: Did you notice that when they go to Newport, there’s a moment where Mrs. Russell is looking at a magazine catalog? I think it is Godey’s.

KBH: That’s so interesting because again, that’s a very, very middle-class way of shopping. You would find a pattern and take it to the dressmaker to have made. Or you would buy something cheap and dress it up yourself with trimmings and ribbons. But someone like Mrs. Russell would be going to Paris and buying her gowns there for the season. Not checking out a catalog!

JG: The Newport scenes in general are really evocative. I revisited Joan Didion’s essay "Seacoast of Despair" after watching the episode. The essay is great—Didion calls Newport “a fantastically elaborate stage setting for an American morality play in which money and happiness are presented as antithetical."

SB: Right—she’s basically saying that these people had all of this money, but they built something so suffocating with it. That’s pretty resonant with the general sense of misery that seems to hang around so many members of high society. There are little rumbles of change that are brewing for some characters. One, notably, is Marian, who seems to be pursuing a career—or at least a pastime—in teaching art at a private girls' school. The decision seems to get mixed reviews in her household.

CO: It is really interesting that Ada isn’t opposed but Agnes is—I wonder what their real Gilded Age counterparts would think of Marian’s teaching? A lot of women from Agnes’s class were getting involved in teaching as charity work in this era, with the aim of “uplifting” the working class. For instance, upper-class women taught things like sewing and reading to working-class girls. A class like this at Grace Church downtown was actually one of the that created the circulating library movement in the city. That movement became a foundational part of the New York Public Library! Since this was an acceptable practice, I wonder if it really would have been such a shock for Marian to teach watercolors to girls from her own class. It does make me wonder if we are going to see Marian’s teaching go in other directions this season though! And it does open up an interesting perspective on what kind of work was acceptable for women in this era.

VP: The show seems to be grappling with how perceptions of class are changing at this time, and there are a couple of examples of how we see upper-class people working. Marian’s teaching is respectable, and so is the architectural profession for the younger Mr. Russell. It's complicated, because the whole idea of "conspicuous consumption" is predicated on the fact that some Gilded Age people had so much money that all that there was left for them to do was to spend it lavishly. That gave rise to the idea that to work at all was considered beneath the upper classes. But here we have some acceptable professions emerging even for the well-born.

SB: There’s also some interesting class mobility stuff happening with the upstairs/downstairs storylines and how someone’s status in either the upstairs or downstairs is not stable. For example, Mrs. McNeil’s father is revealed to be the valet in the Russell household. And, at the end of episode two, it looks like the lady’s maid who worked with Mrs. Russell has herself remarried in the opposite direction!

HM: I thought what the son says at that moment was so good—he just says “Welcome to America!” And that’s sort of the journey they’re trying to portray.

SB: Before we finish, can everyone just go around and say what they're most excited for this season? What you're hoping to see. I know I’m excited to see how they deal with the strike waves that are happening at the times—we hear a little bit about how George Russell is actively colluding with other financiers to actively break strikes, manage his labor problems, things like that. I’m excited to see more of that referenced.

ADH: I’m excited to see what happens with Peggy's story. It feels like the first two episodes kind of took all the changes afoot in Peggy's life, and then reversed them quickly: now she’s back on the Upper East Side, and her baby is out of the picture. What was interesting about Peggy's story was that she's a burgeoning journalist, a la Gertrude Mossell or Ida B. Wells. I’m excited for them to get back to that storyline.

CO: Yeah, I'm excited about that stuff too. Especially to see more about Brooklyn and its literary scene. The real Thomas Fortune was involved in creating some really interesting literary societies in Brooklyn, like the New York Bethel Literary Association, which was noteworthy because both men and women debated important issues of the day, literature and politics. There are just so many places Peggy’s writing can take her, and I am curious to see how her writing connects to political and community engagement as the season continues.

KBH: I also loved the Newport outfits, it’s kind of a fun parallel plot line that I’m eager to see more of. I wanted to highlight our program at the end of next month about Newport and fashion. In the Newport scenes, they’re all wearing white, men are like in light suits. It's this parallel universe summer universe. And I think it will be very interesting when we have the conversation with Rebecca to talk about how the world of New York Society transfers to Newport.

SB: That's a great place to leave off ! For those of you who'd like to take a deeper dive into that very topic should sign up for Keren's upcoming event with the Center for Women's History and textile historian Rebecca Kelly on November 30, "Newport: Gilded Age Fashion Capital." It will be streamed on Zoom for all!