Welcome back to the Center for Women’s History’s analysis of Season Two of The Gilded Age! In this installment of our series, we’re discussing some of the major happenings in Episodes 3 and 4 and offering some additional historical context along the way. You can follow along with our coverage of earlier episodes and seasons here.

Salonee Bhaman (Mellon Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow): I’ll get us started with a quick refresher: Episode 3 begins with Bertha Russell’s tea party in support of the Metropolitan Opera. A lot goes down here, including the reveal that one guest, Mrs. Winterton, is in fact the troublesome lady’s maid we knew as “Turner.” Newly elevated in status through marriage, Mrs. Winterton intimates to Bertha that she seduced George Russell. We also learn that the Met is set to open the same day as the Academy, setting us up for the show-down that Valerie gave us a lead about last week. The new character in town in this episode—the Duke of Buckingham—is big news for society. Vying for his attention quickly becomes one way for the conflict between Bertha Russell and the newly married Mrs. Winterton to escalate.

By the end of episode four, the feud between Mrs. Winterton and Bertha Russell has reached a fever pitch. We find out that the Metropolitan Opera board has promised Mrs. Winterton a central box—initially reserved for Bertha Russell—in exchange for her bringing some people from the Academy of Music into the new opera house. We also soon learn that Mrs. Russell has successfully charmed the Duke of Buckingham enough that he ditches the Wintertons for the Russells in Newport. Both women are furious with each other in their own ways, and it seems to have reached a boiling point.

There’s also another upstairs/downstairs intrigue that’s been building between a woman in society—Mrs. Macneil—and George Russell’s footman, Mr. Collier. We learn that Mr. Collier is actually Mrs. Macneil’s estranged father, who hasn’t seen her since he was divorced from her mother and lost his fortune in the Panic of 1857.

Jeanne Gutierrez (Curatorial Scholar): The Panic of 1857 was a bad one! It was the second time in 20 years that a nationwide financial crisis resulted in a multi-year economic downturn. The first was the Panic of 1837. Both caused a lot of downward social mobility, like we see with Collier: men went bankrupt and their wives and children subsequently lost their place in the world. It could be especially painful because business failures radiated through these intimate social and familial networks. In 1857, not every state had laws protecting married women’s property rights; a man who went bust could lose his wife's assets in addition to his own! It was also fairly common for businessmen to sign for one anothers' debts in the 1840s and 1850s, leaving guarantors on the hook if they defaulted.

SB: Meanwhile, Peggy and Thomas Fortune are working on an article about a new dormitory at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Their plan to visit there together (and unaccompanied by other reporters) fuels speculation about the implied romantic tension between Fortune, who is married, and Peggy. I wanted to pull out two different threads here about the racial politics of the Gilded Age. The first is the sharp distinction between “Northern” and “Southern” racism that the show seems to be making. The second comes out as Peggy mediates between two different visions of racial uplift and liberation proposed by Thomas Fortune and Booker T. Washington. Fortune’s is more confrontational, while Washington’s might be described as accommodationist. I’m curious to hear all your thoughts.

Valerie Paley (Founding Director, Center for Women's History and Sue Ann Weinberg Director of the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library) This was also the first time we learn that T. Thomas Fortune had once been enslaved. It’s clear that going back to the South is a really intense experience for him. Did anyone else notice that Peggy does mention restaurants in New York being segregated—she says something about going in the back door. And, while that was true, it hasn’t really been the way that things have been depicted in the series. Usually, she’s shown just sitting inside a restaurant dining with Marian and it’s all good.

A composite portrait depicting prominent African Americans. From top left: T. Thomas Fortune, Booker T. Washington, Fredrick Douglass, Garland Penn, and Ida B. Wells. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Keren Ben-Horin (Curatorial Scholar): Is Fortune meant to be a stand-in for W.E.B. Du Bois, representing his and Washington’s disparate positions on Black education and civil rights?

CO: The interesting thing is that Thomas Fortune was actually quite close with Booker T. Washington. It was a notable, and sometimes uneasy, alliance, especially because Washington was seen as much more moderate than Fortune, who was regarded as a militant. So it is interesting that they would set him up as such a forceful critic of Washington.

KBH: There’s a moment when Peggy is lamenting that she has been asked to write white characters into her stories in order for magazines to publish them. Thomas Fortune interjects that he still thinks it’s better to make one’s living as a writer than doing some other kind of work. It’s an interesting discourse that he’s tapping into about the kinds of work that are accessible to African Americans. He’s implying that the domestic work that the Tuskegee Institute is training people to do is in fact a lower form of labor that’s going to keep them in a kind of servitude.

Hope McCaffrey (Mellon Foundation Predoctoral Fellow): Yes, and that’s a real debate at the time. I worked on a digital exhibit about the colored conventions of the second half of the 19th century, called the Colored Conventions Project, and the meeting minutes reveal that many Black activists advocated for land ownership and agricultural endeavors as a means of economic advancement. They encouraged Black citizens to abandon service jobs (especially those positions in which they served white people—what many termed “menial employments”) because that work was inherently degrading and demeaning. Some were insistent that those kinds of jobs would not get Black people ahead. I mean, domestic work was often women’s work. And these conventions were often made up of men, who were talking about which professions were respectable and would help get them on equal footing with whites the fastest. There’s a lot of emphasis on education as well, even though there were ongoing debates about how to fund that kind of education.

I also wanted to mention something that stuck out to me as not the most accurate or likely here: when Peggy announces that she’s going down South with Mr. Fortune everyone seems to be scandalized by the fact that she’s traveling alone with a man, rather than by the fact that interstate train travel was very dangerous for Black women. As a single Black woman, Peggy would have been particularly vulnerable: there are many examples of travelers like Peggy being forcibly removed from the “Lady’s Car,” and many of these Black women later sued the railroad companies. In fact, a lot of early civil rights organizing was really galvanized by the experiences that women like Peggy had on trains and streetcars. The real danger to Peggy wouldn’t have been to her reputation, but rather the way that white middle-class travelers and train conductors might have reacted, which could have ended with her being forcibly removed or harmed. And I think that people like her mother would have known that. It was, after all, a Black woman named Elizabeth Jennings Graham, who brought a case which eventually led to the desegregation of the city’s streetcars.

SB: That’s really a great point. It’s sort of where the imagined “respectability politics” of being an unmarried woman would come into conflict with what a scholar like Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham might describe as the solidarity across gender in many African American political spaces.

Labor politics also take on new importance in episodes 3 and 4: we learn that George Russell is facing down a major strike at his steel mill in Pennsylvania when he invites a foreman to his home for lunch to try and diffuse the tension. I was struck by the way that the writers of this show are portraying him as a kinder, gentler version of someone like Andrew Carnegie, who also had steel mills in Pennsylvania.

Anna Danziger Halperin(Associate Director, Center for Women’s History): There’s a line they seem to be trying to walk, where they do gesture at some of the more brutal aspects of capitalism during this era, but are still attempting to develop George Russell into a character for us to root for.

SB:The Russells are starting to emerge as the main protagonists of this show, I think. There isn’t a lot of conflict that they have to withstand. By the end of episode four, Bertha has also successfully wooed the Duke of Buckingham to her home in Newport and bested Mrs. Winterton as his host.

KBH: We’ve talked in the past the way that the show’s depiction of New York City can feel very abstract because we hardly see the streets or get a sense of place in the establishing shots. These elite characters have very little interaction with the outside world, so we’re mostly in the space of their homes. This is also true for how Newport is depicted as a series of isolated gigantic mansions. We know that in reality, Newport was a thriving town, especially in the summer when New York’s and Boston’s 1% came there to vacation, sail, and play sports.

What we do see beautifully is the (visually) stark difference between city life and resort life, especially in how everyone is dressed. Right away the palette is cleansed: we see a lot of white, some navy and white stripes, maybe pastel colors, and even the men change their attire to white, tan, and navy suits and straw hats. It’s the birth of resort fashion: the beach and promenade are a runway for a distinct kind of dressing, the idea that you pack an entirely different wardrobe for a vacation by the sea. And of course this is undergirded by the industrial revolution and the ability to produce more, produce cheaper and faster, and disseminate it more easily through mail-order catalogs and women’s magazines. All of this combined creates the sense that people “needed” more things, that a specialized attire was required, and that it included, of course, accessories, sports equipment, and the like.

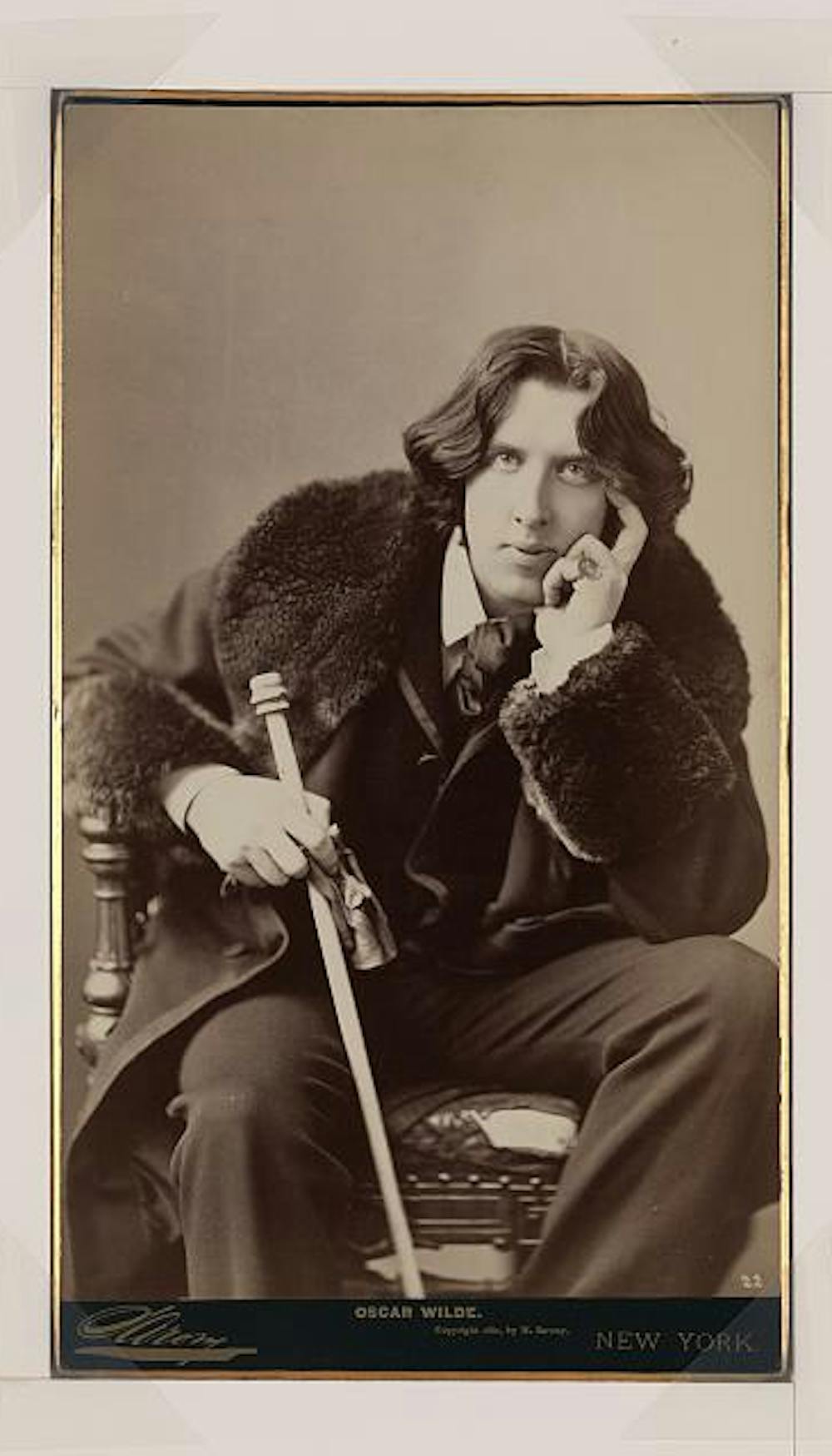

SB: Back in the city, Oscar Wilde makes an appearance, though it’s unclear if he’s going to be a recurring character or just a passerby like Clara Barton was last season. Wilde is here for the premiere of his play Vera, or the Nihilists. No one seems particularly impressed by it, but we do see Oscar Wilde quickly size up Oscar Van Rhijn as not so straight.

CO: I was so excited to see Oscar Wilde show up! I thought that the show captured the dynamics surrounding him quite well: Vera, or the Nihilists flopped in New York (it only ran for seven performances!) and the play was totally panned by critics. But Wilde captivated America's attention. He became a celebrity here quickly for his lecture series, and the impression we get in the show, that the room hangs on his every word, reflects that status.

VP: I was surprised that they didn’t portray Oscar Wilde as more over-the-top. I thought he was jailed, in part, for his unapologetic flamboyance.

Portraits of Oscar Wilde, c. 1882, by Napoleon Sarony. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Digital Archives.

Gilded Age actors Kelli O'Hara and Jordan Sebastian Walle as Aurora Fane and Oscar Wilde. Photographed by Barbara Nitke. Image courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment.

CO: He definitely had a reputation for being flamboyant! I’ve been reading some of the press coverage from Oscar Wilde’s visit to America, and this was really remarked upon. This also makes me think of Salonee’s earlier point that there is a moment of recognition between the two Oscars. Oscar Wilde is wearing a green carnation in his appearance here. Wilde was known for wearing a carnation— to the point that the press commented when he was not wearing it! By the end of the century it was a gay fashion symbol.

SB: Meanwhile, Oscar van Rhijn has set his sights on a new marriage prospect after being rejected by Gladys Russell—a Miss Beaton. It's kind of intimated that she is the illegitimate daughter of Jay Gould, but it's unclear exactly what that means.

VP: In terms of acting, for me, the only believable couple so far, I think, are Oscar van Rhijn and Miss Beaton. They look good as a pair. It still strikes me as unlikely that there would have been such a strong objection to Gladys marrying Oscar based on an idea of romantic love rather than status. I also have to say that I love that this show casts so many Broadway actors!

KBH: I was listening to the official Gilded Age podcast, and I think that Julian Fellowes mentioned something about how the relationship between George Russell and his daughter was based on the relationship between Jay Gould and his daughter.

CO: Yes! That makes me curious about where Gladys’s story is going, if she is somewhat inspired by Gould’s daughter, Helen Gould. We actually have her papers here in the New-York Historical Library and she left quite a different legacy from her father. By the turn of the century she was extremely famous in her own right for her philanthropy. She also lived a somewhat unorthodox life. She attended NYU’s Women’s Law program (as did Emily Roebling, who also shows up this season!) and stayed fairly detached from the machinations of “society” life.

An article from the Salt Lake Tribune speculating about the astrological implications for Helen Gould's Wedding Day. February 9, 1913. Image Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

SB: There’s also another kind of “society” activity that’s being explored in these episodes. After attending a tea party during this episode, Marian is asked to take on another class through the school—but this one is meant to teach poor people how to read and write. The headmistress mentions that the initiative is being spearheaded by Jane Addams. Could we talk a little bit about that?

ADH: Yes! I was curious initially about why they chose Jane Addams, who was a settlement house leader in Chicago, instead of someone like Lillian Wald, a New Yorker.

SB: For those who don’t know, Lillian Wald was the founder of Henry Street Settlement House on the Lower East Side.

ADH: Yes, and a friend of Jane Addams. So, initially it felt like maybe she would have been a better choice—but actually, Wald didn’t start the “Nurse’s Settlement,” as Henry Street was initially called, until 1893—a little bit after this show is set. Regardless of the actual date, this plotline reminded me of something we emphasize in our exhibit Women’s Work: the education sector was one of the big ways that “respectable” women entered the professions. Historians refer to this generation of women sometimes as “New Women;” these more independent, sometimes even college-educated women were striking out from their families in new ways but without totally upending gender expectations. The classroom was seen as an extension of the nursery, so still fit within an acceptable feminine realm. I’m not really sure Agnes would have been so scandalized by Marian taking on this work…but then again, Agnes always has outsized reactions!

HM: I wondered if perhaps the writers meant to reference University Settlement, which was also on the Lower East Side and founded in 1886. It was the founded by three men, and Jane Addams likely visited. I was surprised to see a wealthy New Yorker like Marian being recruited to teach a class there, though—I understood the structure of a Settlement House to be more communal, where instructors also lived in or nearby the house. It would have been quite a journey for Marian to travel all the way down to the Lower East Side to teach that class!

Rivington Street, University Settlement Building Library. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

VP: One of the main points that they’re trying to make in this show seems to be about how social mobility is different in the United States than in England. They draw it out in particular places—like with Turner becoming Mrs. Winterton, or Mr. Collier revealing himself to actually be rather intimately linked to someone in “high society.” But at the same time, there are plot points where we see that social mobility is limited: Mrs. Astor puts Mrs. Winterton back in her place by removing her from the Academy.

SB: Do we think Bertha Russell told Mrs. Astor about Mrs. Winterton?

ADH: It’s hard to say, because Bertha Russell and Mrs. Astor seem like they’re feuding at this point.

SB: The writers have conspicuously left the informant unnamed! Okay, any final thoughts about these two episodes? I feel we’d be remiss to not mention that Ada gets engaged to the rector of St. Thomas’s Church (undoubtedly prompting Agnes’ ire.)

ADH: I think we can draw some parallels to another show in this historical universe, The Buccaneers, which I’m sure everybody has heard about. It’s based on the Edith Wharton novel about new money American women marrying impoverished but titled lords in England. That must be what Bertha has planned for the Duke and her daughter, if I can make a bet about that.