When a landmarked building for a major museum in New York City needs to replace 107 windows that are over 80 years old, you can’t exactly go to Home Depot.

The New-York Historical Society’s current building at 170 Central Park West was first completed in 1908 and underwent a major expansion that was finished in 1938, which is around when most of the current windows were installed. The most public-facing ones on Central Park West, 77th Street, and 76th Street have elegant bronze sashes in keeping with the building’s Beaux-Arts architecture. They’re beautiful, of course, but they aren't up to modern efficiency standards.

“We’ve been in a constant fight to control the humidity and temperature,” says Yashiris Moreta, New-York Historical’s vice president for operations. "We’ve mitigated this over the years, but that was only a temporary fix."

(Left) The New-York Historical Society building under construction in 1906; (right) During the construction of the new wings in 1937.

The only permanent solution would be replacing the windows, which has been on the building’s wish list for almost 20 years now. It wasn’t until 2018 that we received funding to make it happen through special major gifts from our trustees and generous allocations from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, Empire State Development and Market New York under the Office of the Governor's Regional Development Council Initiative, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Working with PBDW Architects—the firm behind our 2017 fourth floor renovation—New-York Historical came up with a proposal that would satisfy the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, while upgrading our building to the 21st century.

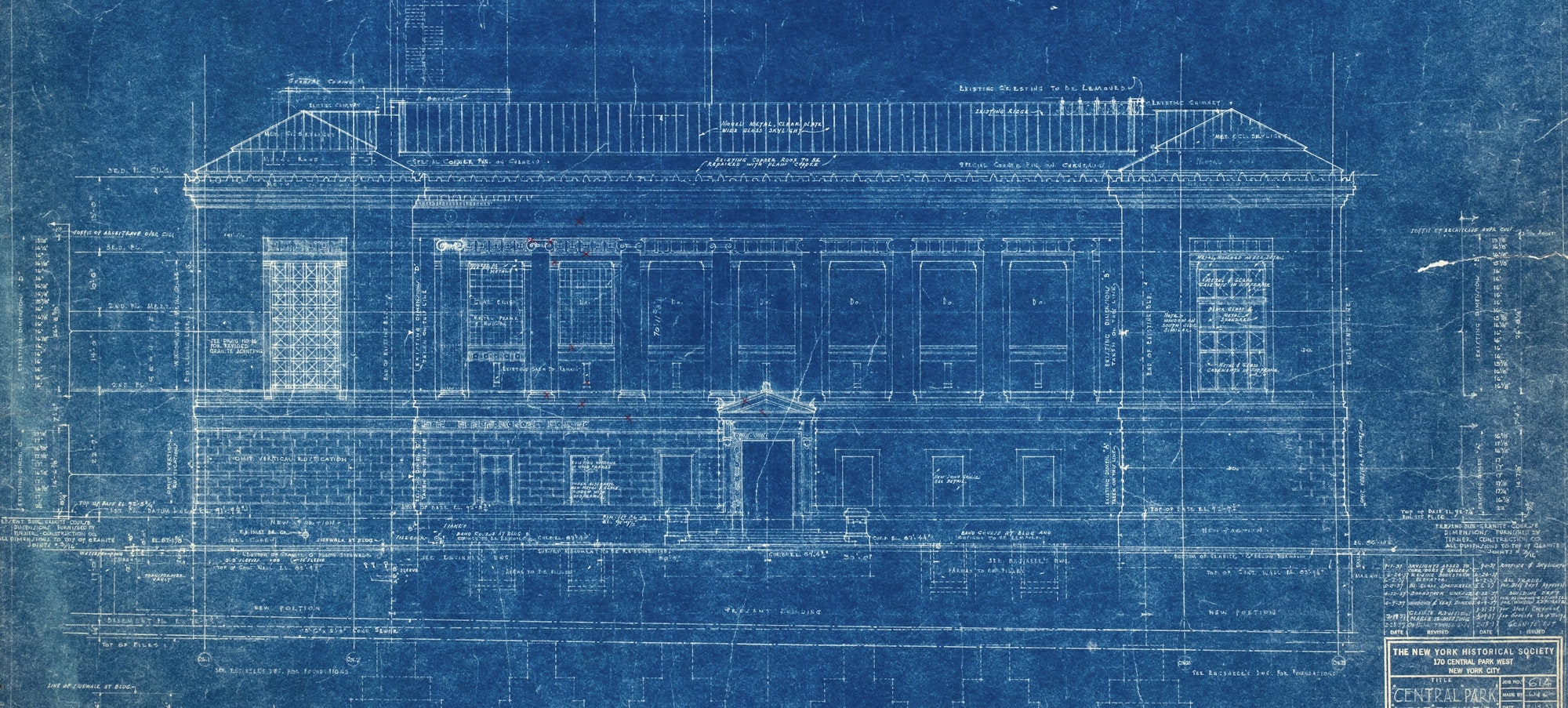

Part of this plan was the removal and restoration of all of the bronze sashes before reinstalling them with modern storm windows inside. There have been many complications along the way, but perhaps none as remarkable as the fact that all of the building’s windows are different sizes. The architect was able to verify this fact by going up to the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library and looking at the original, hand-drawn blueprints. (One of the perks of working in a research institution is that we are very good at keeping records.) “The amount of details from the 1930s is amazing,” Moreta says. “It was great seeing the process of how the drawings looked before and how they look now. You’d think they were computerized, that’s how good they were.”

An architectural drawing from the firm Walker & Gillette dated 1937 that shows the windows of the new wing.

Once the plan was in place, the next step was finding a firm to remove, sand down, and refinish the sashes. During any construction process, New-York Historical is dedicated to getting a certain percentage of minority- or women-owned firms to place bids. But in this case, the task was more complex because there are so few firms that do this kind of historic metalwork in the first place. The architect had a suggestion: Allen Architectural Metal, based in Talladega, AL, and run by renovation specialist Kate Allen. In recent years, the firm has done numerous jobs in New York, including work on the Empire State Building, the Knickerbocker Club, and in Green-Wood Cemetery. They’re currently working on restoration projects at Carnegie Hall and the Waldorf-Astoria, in addition to New-York Historical.

“This building is iconic—it’s part of New York’s history,” says Allen. “I had a professor who used to say, ‘You work in the preservation of memory,’ and I always think about that. We want to do what’s best for the building, but also for the experience of the building. Even when we’re long gone, our work becomes a part of the collective memory.”

Allen has worked in the restoration field for 16 years and took over her family’s business almost two years ago. She’s made it a priority to hire more women into what’s long been a male-dominated field. “I take a lot of pride in trying to change the way the industry is viewed—that’s been difficult but also exciting,” she says. “I have six full-time finishers in New York who are all women, which is really cool.”

(Left) A bronze window sash before restoration; (right) and one that's been restored and reinstalled.

Most of the men who work for Allen's company come from iron-working trades, while the women tend to be trained in artistic practices like ceramics, which requires a deeper understanding of glazes and color. "I had a comment from one of my iron workers: 'You know, we are hiring a lot of women—it’s a little challenging,'" says Allen with a laugh. "And I was like, 'Well, you don’t think it’s been challenging for us for 25 years?'"

The work at New-York Historical is a combination of on-site and off-site repair, with a New York crew working in tandem with the finishing team in Alabama. “The finishing has to coincide with the restoration of the frames on site, so it takes a lot of communication between the Alabama team and the team on site to make sure that the procedures for the patination are the same, the laying of the chemicals, the colors—that’s all really important,” says Allen. Her team is also fixing the opening mechanisms of the windows, including creating custom parts that will allow them to work again. “It goes beyond a visual repair—it was a mechanical repair as well,” she says.

Two of Allen Architectural Metal's finishers, Nora King and Samantha Kupfer, on scaffolding around the New-York Historical Society building.

Right now, the windows project is about a third of the way done, but Moreta is already seeing the results. In rooms and galleries with new windows, there’s a noticeable difference in how much easier it is to control humidity and temperature, something that’s crucial for both visitors and employees and for the art and artifacts on view. “This is really going to help us with energy compliance," says Moreta.

The project is slated to be done by the end of 2024 and, just like those 1930s blueprints, become another key stopping point in the 220-year journey of New-York Historical’s physical space. “You know, I’m glad that Landmarks said that we had to keep the bronze sashes,” says Moreta. “Stuff like that has sentimental value for a lot of people. The fact that you have a window that’s been here for almost 100 years, and you’re able to keep it—I think it’s magical.”