Composite Nationality

“We are a country of all extremes—, ends and opposites; the most conspicuous example of composite nationality in the world.

Our people defy all the ethnological and logical classifications. In races we range all the way from black to white, with intermediate shades which, as in the apocalyptic vision, no man can name a number.

In regard to creeds and faiths, the condition is no better, and no worse. Differences both as to race and to religion are evidently more likely to increase than to diminish.

We stand between the populous shores of two great oceans. Our land is capable of supporting one fifth of all the globe. Here, labor is abundant and here labor is better remunerated than any where else. All moral, social and geographical causes conspire to bring to us the peoples of all other over populated countries.”

In “Composite Nation,” Frederick Douglass told his audiences that Americans were a people of composite nationality. Then he directly addressed the question of Chinese immigration. Douglass knew that a growing and often violent anti-Chinese movement sought to close the borders (see "Lessons of the Hour" in Hope) to immigrants from China and deny equal rights to those already here. But Douglass publicly supported the Chinese. It was a courageous position given the widespread sentiment against them.

Douglass believed that immigrants would be good for the nation—and that America would be good for immigrants. He called for more than a friendly welcome. He argued that the Chinese should be granted every freedom Americans expect for themselves: to become citizens, vote, and run for office. Beyond that, Douglass thought an open policy toward immigrants would strengthen the United States and create a more just democracy.

Douglass was not the only person who campaigned for a more inclusive country. The same year he debuted “Composite Nation,” German immigrant and artist Thomas Nast published an engraving that embodied the same ideal. In addition, Chinese American Wong Kim Ark took his fight for citizenship all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. And the Latina activists of La Liga de las Hijas de Cuba demonstrated that immigrant populations could have positive impacts in the United States as well as in their native countries. These activists, and so many more, reinforced Douglass’ point that the country’s strength lay in its composite nationality.

Frederick Douglass believed that one of the United States’s greatest strengths was that any person could come from anywhere in the world and become an American.

Frederick Douglass believed the United States should embrace the diversity of its population.

After the Civil War, anti-Chinese sentiment coalesced into the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Immigrant groups living in the United States supported initiatives to bring American ideals to their homelands.

What did Frederick Douglass mean when he used the phrase “composite nationality”?

Why did Frederick Douglass believe that embracing the United States’s composite nationality was the best way forward for the nation?

What struggles did different immigrant groups face in the years after the Civil War?

- Life Story: Wong Kim Ark

The story of a Chinese American man who confirmed the right of birthright citizenship for all children of immigrants.

Topics: Immigration, Fourteenth Amendment, Chinese American history, AAPI history, Chinese Exclusion, United States v. Wong Kim Ark

- Resource: Dual Identities

This image of La Liga de las Hijas de Cuba illustrates how Latinx immigrant women embraced their dual identities to campaign for change in their homelands.

Topics: Latinx history, Ten Years War, women’s activism, Latin American political groups in the United States

- Resource: Enduring Exclusion

Two documents that demonstrate how exclusion impacted Chinese people living in the United States.

Topics: immigration, Chinese Americans, Chinese Exclusion Act, Geary Act, AAPI, legal history, activism

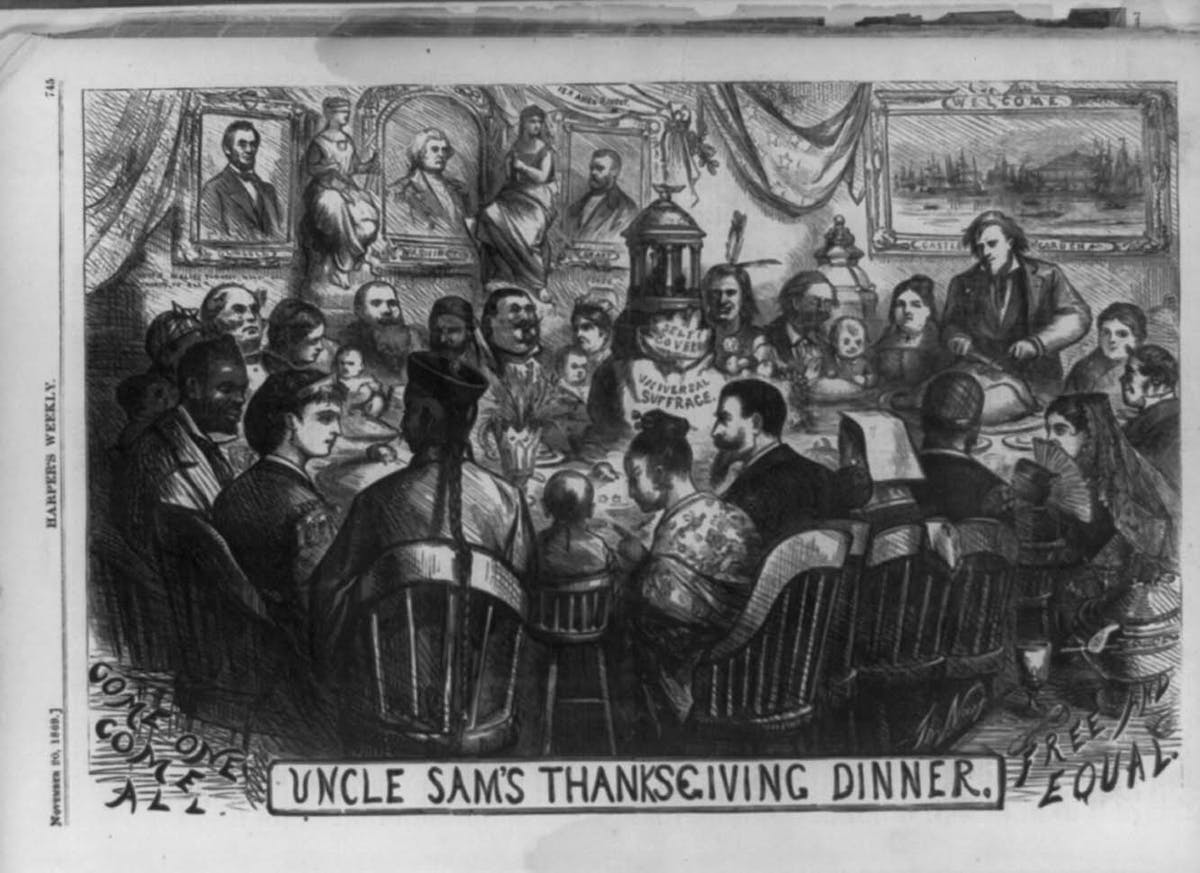

- Resource: Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner

This Thomas Nast drawing captures the spirit of Frederick Douglass’ hope for a “composite nation.”

Topics: Thomas Nast, immigration, political art

Life Story: Wong Kim Ark

Wong Kim Ark (ca. 1873–1945)

The battle for birthright citizenship

Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco around the year 1873. His parents, Wong Si Ping and Wee Li, were both immigrants from China. They could not become U.S. citizens because of the Naturalization Law of 1802 barred people of color from becoming citizens. But Wong was not an immigrant. He was born in the United States after the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, which stated that any person born in the United States was automatically granted citizenship regardless of their race.

Wong grew up during a time when it was dangerous to be a Chinese American. Many white Americans believed that Chinese immigrants were taking their jobs. States passed restrictive laws that prevented Chinese immigrants from living and working where they wanted to. And white people sometimes physically attacked Chinese people and communities to send the message that they were not welcome. All of this anti-Chinese sentiment culminated in 1882 when the U.S. government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. This law made it illegal for most Chinese people to enter the country. It was the first time the United States restricted immigration based on race. The restriction against Chinese immigration continued until 1943.

Wong was born in the United States, so the Chinese Exclusion Act should not have applied to him. In 1890, when he was about 17 years old, he traveled back to China to visit family and conduct some business. When he returned, the customs agent recognized that he was a U.S. citizen and allowed him to re-enter the country. But in 1895, after a second visit to China, a different customs inspector tried to claim that he was not a U.S. citizen because his parents were not. Wong was placed in detention until a court could rule on his case.

With help from the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, Wong hired lawyers to take his case to court. He was held on steamships in San Francisco Bay for five months before a California judge ruled that he was indeed a U.S. citizen. But the U.S. government appealed the decision, bringing it before the Supreme Court. Government lawyers argued that Chinese people were permanently under the jurisdiction of China and incapable of assimilating into U.S. society. Their case was built on the same racist ideas that made daily life for Chinese Americans so challenging.

In 1898, the Supreme Court rejected the government’s argument and ruled in Wong’s favor. In the process, they confirmed that the Fourteenth Amendment granted the fundamental right of citizenship to any person born in the United States regardless of race or the immigration status of their parents. In its 6 to 2 decision, the court said that if Wong was not a citizen, then no child of immigrants could be a citizen. All the children of German, Irish, English, Scottish, and other European immigrants would lose their citizenship status. Such a ruling would cause complete chaos. It could not be allowed.

The United States v. Wong Kim Ark was a landmark case that clarified how citizenship worked in the United States. But it did not solve the discrimination and inequality Chinese Americans faced in their daily lives. Wong still needed to carry identification papers when he traveled to China in case someone questioned his right to return to the United States. He also needed to rely on white witnesses to affirm his citizenship. This was not something that any white person had to do, even if they were very recent immigrants.

Wong continued to demand the same rights as any white U.S. citizen. He traveled back and forth to China and married a Chinese woman and started a family. In 1910, he tried to bring his eldest son to the United States. He claimed that his son should have U.S. citizenship just like the children of white Americans that were born abroad. His son was sent home because officials argued that Wong failed to prove that the boy was his son. But three of his younger sons were admitted to the country as full citizens between 1924 and 1926. In fact, his youngest was drafted into the U.S. military during World War II and had a career in the U.S. Merchant Marines.

Sometime after the end of World War II, Wong moved permanently to China, where he passed away on an unknown date. His descendants are still living in the United States and sharing his story today.

Click here for a video of this life story.

- assimilating

Becoming a part of something.

- Chinese Benevolent Associations

Groups formed by Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans to provide financial and legal aid to their communities.

- Chinese Exclusion Act

The 1882 federal law that banned most Chinese people from immigrating to the United States.

- customs inspector

A person who checks the people and goods entering the United States to make sure no person or item is entering illegally.

- detention

The practice of holding someone in government facilities until their immigration status can be determined.

- Fourteenth Amendment

The amendment to the U.S. Constitution that established the principal of birthright citizenship.

- jurisdiction

Laws.

- Naturalization Law of 1802

An act that established being free and white as a requirement for people seeking U.S. citizenship.

- Supreme Court

The highest court in the United States.

- U.S. Merchant Marines

The commercial shipping enterprise of the U.S. government.

- World War II

The global conflict that was fought between 1939 and 1945. The United States and China were allies in this war.

Why was Wong Kim Ark able to claim U.S. citizenship when his parents could not?

How did the Supreme Court case United States v. Wong Kim Ark change the understanding of U.S. citizenship?

What challenges did Wong Kim Ark and the Chinese American community continue to face after his landmark Supreme Court decision?

In what ways does Wong Kim Ark embody Frederick Douglass’ ideal of composite nationality? What does his story reveal about U.S. attitudes toward the concept in the late 19th century?

To learn more about the challenges facing Chinese Americans in the second half of the 19th century, see Enduring Exclusion.

Wong Kim Ark’s landmark Supreme Court case was decided almost 20 years after Frederick Douglass first began delivering his “Composite Nation” speech (Composite Nation on Tour). Ask students to read the sections of the speech where Douglass addressed Chinese immigration, and then write an article about Wong Kim Ark’s case from Frederick Douglass’ perspective.

Compare and contrast the life story of Wong Kim Ark with that of Wong Chin Foo (in Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion). What methods did each man use to call for better rights for Chinese people in the United States? What were the results of their actions?

Supplement this life story with the following two videos produced by the New-York Historical Society for the exhibition Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion: United States v. Wong Kim Ark and Paper Sons and Daughters.

Use the following resources to provide students with the historical context for Wong Kim Ark’s life and court case: School Segregation; Enduring Exclusion; and Naturalization Laws, The Chinese Exclusion Act, The Rock Springs Massacre, Ellis Island, and Paper Sons and Daughters (in Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion).

For more resources about the history of Chinese people in the United States, see Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion.

To learn about the specific experiences of Chinese women in America, see Women & the American Story.

Resource: Dual Identities

Carlos Manuel de Céspedes was a sugar plantation owner in eastern Cuba. On October 10, 1868, he freed the enslaved people on his plantation and declared independence from Spain. Soon, about 12,000 men joined Carlos Manuel to fight for Cuban independence. The conflict that followed is known today as the Ten Years War (Nueva York: 1613-1945). It was part of a larger wave of anti-Spanish rebellions (Nueva York: 1613-1945) that swept through Spain’s American colonies in the 19th century.

The large population of Cuban immigrants living in the United States played an active role in the Cuban fight for independence from Spain. But groups like the Junta Revolucionaria de Cuba y Puerto Rico (Revolutionary Junta of Cuba and Puerto Rico) did not allow women to join. To make her voice heard, Emilia Casanova de Villaverde founded La Liga de las Hijas de Cuba (The League of the Daughters of Cuba) in New York City in 1869. La Liga’s members were women from Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Latin America. As the newspaper illustration shows, they met in members’ homes to raise money and organize support for the ongoing fight to end Spanish colonial rule in the Americas.

Newspapers called the women of La Liga “active and wide awake ladies.” Many became U.S. citizens and embraced their dual identities, and they directly asked the U.S. government to aid their native homelands. Their activism was evidence that the diverse population of the United States could have profound impacts on governments and societies all over the world.

- Junta Revolucionaria de Cuba y Puerto Rico

The men-only political club that supported Cuban and Puerto Rican independence from Spain.

- La Liga de las Hijas de Cuba

A political club founded by and for women that supported the end of Spanish colonial rule in the Americas.

What can we learn about La Liga de las Hijas de Cuba from this image? What more do you want to know?

Why did women have to form their own society to support Cuban independence from Spain?

What does this story demonstrate about the possibilities of Frederick Douglass’ idea of “composite nationality”?

For a larger lesson about the Cuban immigrant community’s role in the Ten Years War, teach this image together with the life story of Emilia Casanova de Villaverde and Ten Years War in Cuba and New York (in Nueva York: 1613-1945).

After discussing this image, ask students to read the life story of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (Absolute Equality) and then write a short paper on the particular challenges women activists faced in the 19th century.

Frederick Douglass believed the diversity of the U.S. population would give the country strength in international affairs. After examining this resource, ask students to read the corresponding passages from “Composite Nation” (Composite Nation on Tour) and then debate whether this resource supports or detracts from his argument.

For more resources about the history of Latinx people in the United States, see Nueva York, 1613-1945.

To learn more about Latinx women in American history, see Women & the American Story.

Resource: Enduring Exclusion

Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act (Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion) in 1882. This law banned most Chinese people from entering the United States. It also continued the long-standing ban on Chinese immigrants becoming U.S. citizens. It was the first time a U.S. law specifically barred immigrants based on race.

The 1892 Geary Act (Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion) extended the Chinese Exclusion Act. It also introduced new regulations intended to assert government control over Chinese residents. It stated that any Chinese person who lived in the United States was required to register with the government. Chinese people were also given photo identification papers that they had to carry at all times to prove they were in the country legally. If Chinese people were caught without their papers, they could be deported. This was the first time any group of people in the United States was required to carry identification. These rules caused tremendous difficulty and anxiety for Chinese people. The laws excluding Chinese immigrants and the special restrictions governing Chinese Americans remained in effect until 1943.

The first image is an example of the photo identification Chinese Americans were forced to carry after the Geary Act was passed in 1892. The laws stated that the photos used for identification papers should be taken in the same style as criminal mug shots. This requirement made it appear as though Chinese Americans and immigrants were criminals.

But Chinese Americans did not give up hope. The second image is a membership card for the Chinese Equal Rights League. This group was founded by Wong Chin Foo (Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion) to protest the Geary Act and the systemic oppression of Chinese people in the United States. The Chinese Equal Rights League held a large meeting in New York City to draw attention to the cause. It also urged members to write letters, march in protest, and commit acts of civil disobedience. These efforts were unsuccessful.

- Chinese Benevolent Associations

Groups formed by Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans to provide financial and legal aid to their communities.

- Chinese Exclusion Act

The 1882 federal law that banned most Chinese people from immigrating to the United States.

- Geary Act

The 1892 federal law that extended the Chinese Exclusion Act and created regulations governing Chinese people living in the United States.

- mug shot

A photo of a person’s face made for official documents, most commonly for police records.

Why was the Geary Act harmful to Chinese Americans?

What do these two documents reveal about Chinese American responses to the Geary Act?

How did the Geary Act undermine the ideal of composite nationality?

Ask students to study these images together with the Plessy v. Ferguson (Hope) resource and then write a short essay about how the U.S. government rejected Douglass’ idea of composite nationality (Composite Nation on Tour) in the final years of the 19th century.

Read the life story of Wong Kim Ark to learn about how Chinese people born in the United States asserted their rights as citizens in this period of legal restrictions.

After exploring this resource, ask students to read “Composite Nation” (Composite Nation on Tour) and then write a short letter in support of Chinese activists in the voice of Frederick Douglass.

Teach these images together with any of the following for a larger lesson about the challenges and successes of Chinese Americans in the 19th century: School Segregation, Life Story: Wong Kim Ark; and Naturalization Laws, 1790-1870, The Chinese Exclusion Act, The Rock Springs Massacre, Ellis Island, and Paper Sons and Daughters (in Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion).

For more resources about the history of Chinese people in the United States, see Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion.

For more resources on the history of Chinese women in the United States, see Women & the American Story.

Resource: Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner

Cartoonist Thomas Nast was 16 years old when he immigrated to the United States from Bavaria in 1846. As a young man, he studied drawing and pursued a career as an artist. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper offered him a job as a staff artist in 1855. By 1858, Harper’s Weekly and the New York Illustrated News were also publishing his work.

Nast rose to national fame during the Civil War, and his influence grew in the following decades. His drawings and cartoons offered readers inspiring and thoughtful commentary on current events. He is most famous for his cartoons depicting the corruption of New York City’s Tammany Hall. He is credited with helping to end the long, corrupt career of Tammany leader, William M. “Boss” Tweed.

Thomas Nast drew this extremely hopeful depiction of how the Fifteenth Amendment might reshape U.S. society the same year Frederick Douglass began his “Composite Nation” tour (Composite Nation on Tour). In the drawing, the symbolic figures “Uncle Sam” and “Columbia” are hosting a Thanksgiving dinner for men and women of many different races and nations. Three of Nast’s heroes—Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, and Ulysses S. Grant—are prominently featured on the wall. There is also a painting of Castle Garden, New York City’s immigration station before Ellis Island.

Thomas used stereotypes that are considered offensive today to help his readers easily identify the many different nationalities gathered at the feast. But the text in the bottom corners of the drawing reveals that his intent was not to harm. In fact, he wanted to inspire people to embrace and celebrate the diversity of the U.S. population.

- Abraham Lincoln

The 16th president of the United States (1861–1865), who guided the country through the Civil War and the abolition of slavery.

- Bavaria

A kingdom that would become part of Germany in the late 19th century.

- Columbia

The female personification of the United States of America.

- Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

An American news magazine famous for its illustrations of current events.

- George Washington

The first president of the United States and general of the Continental Army during the American Revolution.

- Harper’s Weekly

An American news magazine that published Thomas Nast’s most famous political cartoons.

- New York Illustrated News

An American news magazine that published some of Thomas Nast’s earliest illustrations.

- Tammany Hall

A New York City political organization that was infamous for its corruption.

- Ulysses S. Grant

The 18th president of the United States (1869–1877), and a general of the Union Army during the Civil War.

- Uncle Sam

The male personification of the United States.

- William M. “Boss” Tweed

The leader of the corrupt Tammany Hall political organization brought down, in part, by Thomas Nast’s political cartoons.

What is the message of this drawing? How has the artist conveyed that message through images and text?

How do you think Thomas Nast would feel about Frederick Douglass’ idea of “composite nationality”? Support your answer with evidence from this drawing.

How does this drawing make you feel? Has the United States lived up to the spirit of this 1869 drawing?

This drawing and the Composite Nation (Composite Nation on Tour) speech paint a very hopeful picture of the United States’s prospects after the Civil War. To help students better understand the full picture of American attitudes towards diversity in the 19th century, use any of the following: Life Story: Frederick Douglass (Composite Nation on Tour); Life Story: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Philadelphia Streetcar Desegregation, White Resistance (Absolute Equality); Life Story: Wong Kim Ark, Enduring Exclusion; and Life Story: Joseph Douglass, Plessy v. Ferguson, and “The Lessons of the Hour” (Hope).

The message of this drawing is still relevant today, but some of the images and symbols are outdated for a modern audience. Ask students to brainstorm how they would update this image to speak to a modern audience. What immigrant populations should be seated at the table? What images should hang on the walls?

Give students printed copies of this drawing and Frederick Douglass’ “Composite Nation” (Composite Nation on Tour) speech and invite them to create a collage that pulls phrases and symbols from both sources.