Emancipation

Emancipation

Unit Introduction

Explore the role of President Lincoln in the context of other factors that played crucial parts in the end of slavery.

Slavery did not end in an instant. The process required many actors, hard work sustained over time, and sheer will.

Lincoln’s ideas about slavery and race, as well as his executive power, evolved over time.

African Americans—from Frederick Douglass, to enslaved people who freed themselves, to Black recruits and volunteers on the battlefield—played essential roles in the abolition of slavery.

The Civil War is perhaps the most complex period of our nation’s history. Perennial questions for historians are how slavery ended, and which people and events contributed to its end. This unit seeks to put the role of President Lincoln in the context of other factors that played crucial parts.

These materials focus primarily on key developments from 1861 to 1863, the period leading to the Emancipation Proclamation, and the changes that proclamation brought. They trace Abraham Lincoln’s initial reluctance to take direct action against slavery, his evolving outlook, and his growing willingness to use his power as commander in chief. They also examine the important role played by Black Americans, from the contrabands who escaped slavery and made it to Union lines to the moral and political arguments eloquently put forward by Frederick Douglass.

How did slavery end in the United States?

How did Lincoln use the power of the presidency to enact the Emancipation Proclamation?

How did the actions of enslaved and free African Americans change the course of the Civil War?

These items in this unit can be used individually or collectively and in any order that works for your classroom. Some teachers may choose to introduce the life stories first, to put key players at the forefront before students explore the rest of the story. Others may want students to dive into specific primary resources to glean as much information as possible before viewing the wider narrative. The unit has been designed so that either approach works.

Click on the materials below to begin exploring emancipation.

- Video: Lincoln and Emancipation

This video traces Abraham Lincoln’s evolving positions on slavery and emancipation, starting with his 1860 campaign for the presidency.

Curriculum Connections: Lincoln’s election, the Civil War, slavery, abolition, emancipation

- Resource: Contrabands

A resource examining the important role of Black American “contrabands” during the Civil War and the precarious position they held within the Union Army.

Curriculum Connections: Civil War, self-emancipation, Union Army

- Resource: Border States

In this letter, President Lincoln explained and defended his decision to overrule Major General John C. Frémont’s 1861 proclamation that had declared the freedom of all enslaved people in Missouri.

Curriculum Connections: Civil War, border states, emancipation

- Resource: Congress Takes Action

This collection of materials explores the actions that Congress began to take in 1862 to push for emancipation.

Curriculum Connections: Civil War, Congress, Republican Party, Radical Republicans, emancipation, military service

- Resource: The Evolving Language of the Emancipation Proclamation

The three versions of the Emancipation Proclamation that Lincoln wrote show shifts in his approach to abolition.

Curriculum Connections: Civil War, emancipation, Union Army, military service

- Resource: Frederick Douglass Responds

Two documents explore Frederick Douglass’s response to Lincoln’s views on emancipation.

Curriculum Connections: abolitionists, emancipation, Civil War, Union Army, military service

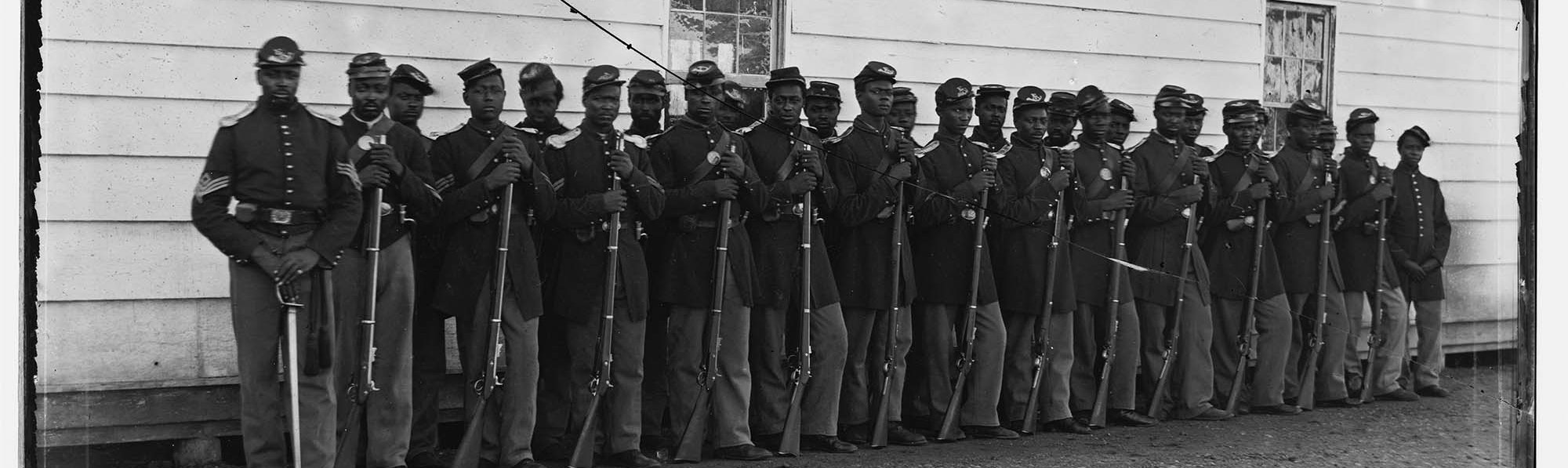

- Resource: Black Soldiers

This resource includes images and text that focus on Black regiments and soldiers in the Union Army.

Curriculum Connections: emancipation, Civil War, Union Army, military service

- Resource: Juneteenth

This resource examines how news of the Emancipation Proclamation spread among enslaved people in the South.

Curriculum Connections: emancipation, Reconstruction

- Life Story: Abraham Lincoln

The story of the president who led the country during the Civil War.

Curriculum Connections: election of Lincoln, secession, slavery, Civil War, emancipation, Thirteenth Amendment

- Life Story: Frederick Douglass

The story of a prominent abolitionist who advocated for emancipation through speeches and writing.

Curriculum Connections: self-emancipation, abolitionists, Abolitionist Movement, military service

Video: Lincoln and Emancipation

This video traces Abraham Lincoln’s evolving positions on slavery and emancipation, starting with his 1860 campaign for the presidency.

This video was created by the New-York Historical Society in collaboration with Makematic.

In this video, historians trace Abraham Lincoln’s evolving positions on slavery and emancipation, beginning with his campaign for the presidency in 1860. They describe the narrow path the president had to tread to win the election and maintain the heterogeneous coalition that supported the Union. And they follow Lincoln’s thinking about the legal options open to him as commander in chief, which ultimately produced the Emancipation Proclamation.

David M. Rubenstein is Co-Founder and Co-Chairman of The Carlyle Group, one of the world’s largest and most successful private investment firms. Established in 1987, Carlyle now manages $293 billion from 26 offices around the world.

Mr. Rubenstein is Chairman of the Boards of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the Council on Foreign Relations, the National Gallery of Art, and the Economic Club of Washington; a Fellow of the Harvard Corporation; a Trustee of the University of Chicago, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins Medicine, the Institute for Advanced Study, the National Constitution Center, the Brookings Institution, and the World Economic Forum; and a Director of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, among other board seats.

Mr. Rubenstein is a leader in the area of Patriotic Philanthropy, having made transformative gifts for the restoration or repair of the Washington Monument, Lincoln Memorial, Jefferson Memorial, Monticello, Montpelier, Mount Vernon, Arlington House, Iwo Jima Memorial, the Kennedy Center, the Smithsonian, the National Archives, the National Zoo, the Library of Congress, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Mr. Rubenstein has also provided to the U.S. government long-term loans of his rare copies of the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th Amendment, the first map of the U.S. (Abel Buell map), and the first book printed in the U.S. (Bay Psalm Book).

Mr. Rubenstein is an original signer of The Giving Pledge; the host of The David Rubenstein Show and Bloomberg Wealth with David Rubenstein; and the author of The American Story, How to Lead, and The American Experiment.

David W. Blight is Sterling Professor of History, African American Studies, and American Studies at Yale University. He is the author of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, among other works about the Civil War.

H. W. Brands holds the Jack S. Blanton Sr. Chair in History at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, and the Struggle for American Freedom and other books about American history.

Drew Gilpin Faust was president of Harvard from 2007 to 2018, the first woman to serve in the role. She is the author of This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War and other studies of the Civil War.

Eric Foner, DeWitt Clinton Professor Emeritus of History at Columbia University, is the author of The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery and other volumes devoted to the Civil War and Reconstruction, slavery, and nineteenth-century America.

Lincoln’s approach to slavery and emancipation evolved over time. Watch the video, and select the key points where his beliefs are expressed. Chart them on a timeline. Write a brief description of how and why the president’s thinking changed about such a crucial issue.

Using this video and other materials in the unit, make a list or timeline to chart the factors that contributed to the end of slavery in the United States.

Resource: Contrabands

Images and a document examining the important role of Black American “contrabands” during the Civil War and the precarious position they held within the Union Army.

--This, without doubt, will be the most difficult problem with which Congress will have to grapple. And yet it can not be neglected. As was clearly foreseen at the outbreak of hostilities, wherever our armies march slavery disappears before them. Not that our troops are necessarily abolitionists. But the slaves run away or are abandoned as the troops approach. An old negro found at Hampton by one of our regiments, the other day, being asked if he had run away from his master, replied, “No; massa ran away from me!” It must be so throughout the revolted section of the country. As our armies advance the masters will run away from the slaves, or the slaves will run away from the masters. In either event the result will be the same.

Congress must face the problem of runaway slaves. When the Union Army marches into the South, the institution of slavery collapses. Enslaved people run away from slaveowners, and slaveowners abandon enslaved people.

Now so long as we are on the border of Virginia, and the runaways and derelicts amount to a few hundred in number, it is easy to provide for them, and to keep books of account with their reputed owners. But when the refugees are counted by thousands and tens of thousands what is to be done with them? This is a question which should not be left to the discretion of the Federal commanders. Men’s opinions will differ:

There are only a few hundred refugees now, and we can take care of them. But what will happen when there are thousands and thousands? What do we do with them?

Government should have a uniform policy. The people of the North, moreover, who will be sorely taxed to provide means to put down this rebellion, have a right to know whether any part of their money will be used for the support of thousands of fugitive slaves who, after the war, are to be returned to their conquered owners. The question, we admit, is very embarrassing. Every possible solution presents grave difficulties. But it is the duty of Congress to decide it one way or another, and we trust members will go to Washington prepared to assume the responsibility.

It is not the job of individual Union officers to answer this question, it is the federal government’s. We need a policy that applies to every situation. Northern taxpayers need to know if their taxes will be spent on keeping fugitive slaves alive until they are returned to their owners after the war. Congress has to decide this question.

Harper’s Weekly, July 6, 1861.

--This, without doubt, will be the most difficult problem with which Congress will have to grapple. And yet it can not be neglected. As was clearly foreseen at the outbreak of hostilities, wherever our armies march slavery disappears before them. Not that our troops are necessarily abolitionists. But the slaves run away or are abandoned as the troops approach. An old negro found at Hampton by one of our regiments, the other day, being asked if he had run away from his master, replied, “No; massa ran away from me!” It must be so throughout the revolted section of the country. As our armies advance the masters will run away from the slaves, or the slaves will run away from the masters. In either event the result will be the same.

Now so long as we are on the border of Virginia, and the runaways and derelicts amount to a few hundred in number, it is easy to provide for them, and to keep books of account with their reputed owners. But when the refugees are counted by thousands and tens of thousands what is to be done with them? This is a question which should not be left to the discretion of the Federal commanders. Men’s opinions will differ:

Government should have a uniform policy. The people of the North, moreover, who will be sorely taxed to provide means to put down this rebellion, have a right to know whether any part of their money will be used for the support of thousands of fugitive slaves who, after the war, are to be returned to their conquered owners. The question, we admit, is very embarrassing. Every possible solution presents grave difficulties. But it is the duty of Congress to decide it one way or another, and we trust members will go to Washington prepared to assume the responsibility.

Harper’s Weekly, July 6, 1861.

Before the Civil War, many enslaved people courageously fled brutal conditions to seek freedom, and some succeeded. In 1850 this became much harder, because the Fugitive Slave Law made the return of runaways a responsibility of the federal government, not the individual states. It also required Americans, including those in the North, to help return fugitives to their owners. This meant the runaways were not safe until they reached Canada. But early in the Civil War, enslaved people in the South found a closer opportunity. As the Union Army moved into parts of the South, runaways needed only to reach Union-held territory.

In the beginning, individual military commanders decided how to respond when fugitives arrived at their posts. The Union Army returned some to the people who claimed ownership over them but allowed most to remain. On May 23, 1861, three Black men asked for refuge at the Union-held Fortress Monroe in Virginia. The Fugitive Slave Law was still in effect. But when a slaveholder claimed to own the men and demanded their return, the fort’s commander, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, refused. He called the men contrabands. This word was usually used in the singular, contraband, to refer to enemy possessions that had military value, like guns and ammunition, and these could be confiscated by the opposing side. Butler applied it to human beings who had successfully fled slavery. His argument was that many enslaved people were working for the Confederate Army. They were building fortifications, keeping plantations running, and growing the South’s food. They were essential to Confederate hopes for victory. President Lincoln had promised not to interfere with Southern slavery, but he approved of Butler’s action.

“Contrabands” came to define the once-enslaved African Americans who sought the protection of the Union Army. By the end of July 1861, over 850 people had arrived at Fortress Monroe. Hundreds more made their way to other Union-held locations in the South. Union officers put the men and women to work as laborers and cooks, set up tents for them to live in, and opened schools (for a photo of contraband students, click here). On August 6, 1861, the First Confiscation Act freed enslaved people who were assisting the Confederate Army. In July 1862, the Second Confiscation Act freed all enslaved people who came within Union lines, if their owners were Confederates, and made it illegal for any federal officer to return them to slavery.

Many runaways bore clear signs of abuse, which made the brutality of slavery real for Union soldiers and for many in the North. And their sheer numbers raised difficult questions. Were they still property, as the Confederacy insisted? When the war ended, would they be returned to slaveholders even if the Union won? Did the federal government have the right to free them? President Lincoln was trying to avoid talking or taking action about slavery. But the presence of the contrabands on Union territory, and the stories about them in Northern newspapers, made the issue impossible to ignore.

Nearly half a million African Americans were defined by the Union Army as contrabands over the course of the Civil War.

Daily newspapers in the North provided dramatic reporting about the contrabands. Weekly publications, especially Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly, included engravings based on artists’ sketches or photographs made on-site. Both weeklies were pro-Union, and they covered the Civil War extensively. They portrayed the contraband story as real and urgent. Leslie’s and other newspapers called the influx of runaways a “stampede.” Harper’s asked, “What is to be done with them?”

The Civil War was the first war to be extensively photographed, especially by photographers working for the well-known Mathew Brady Studio. They included James F. Gibson, who took the Cumberland Landing photo, and Timothy O’Sullivan, who recorded the escape on the Rappahannock. Brady photographs were sometimes copied by engravers and published in the weeklies. Brady also exhibited photos in his studio and sold printed copies of them. Many people saw these images.

"The Slavery Question,” from Harper’s Weekly, is part of a longer article about the four topics Congress would deal with in a special session beginning July 4, 1861. The first three concerned enlarging the army and navy and financing the war. The fourth focused on “the most difficult” issue—the flood of enslaved people who had run away or been abandoned.

In addition to providing details about the contrabands, these images and text show how the drama was presented to Northern audiences. They increased the pressure on the Lincoln administration to resolve the questions raised by the hundreds of thousands of people who had escaped from or been abandoned by slaveholders.

- abolitionists

People who wanted slavery to end immediately and permanently in every part of the United States.

- contraband

Usually, goods that are used for military purposes in a war and can be confiscated by the other side. In the plural, “contrabands” referred to the enslaved people who fled to Union territory.

- derelicts

Property that has been abandoned.

- engravers

Artists who use carving tools to copy a photo or drawing onto a block of wood for printing. In the Civil War, engravings were used to produce illustrations in publications like Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly.

- foreseen

Predicted.

- massa

Master, in the dialect often used by white authors writing in the voice of an enslaved person. Today it is recognized as a racially offensive term.

- quandary

A problem that requires making a hard choice.

- reputed

Supposed, or thought to be.

- revolted section

The part of the country in rebellion during the Civil War; the Confederate states.

- weeklies

Newspapers or journals published once a week.

Why would Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper’s Fortress Monroe caption use the word stampede? What do you think the artist or photographer saw and heard? What would “stampede” communicate to readers?

Before the Civil War, most runaway enslaved people were young men. Why do you think the two photos show so many women and children?

When people in the North read about the contrabands and saw actual photographs of people who had escaped slavery, what do you think their reactions were? What do you think and feel when you look at them?

Harper’s asked for a consistent government policy but said that “every possible solution presents grave difficulties.” Brainstorm some of the ways the US government might have dealt with the influx of enslaved people into Northern-held territory early in the war.

Select one of the images in this resource and describe it in detail. Think about the numbers of people shown, their ages, what the relationships among the people might be, what they are doing. Speculate about what they might be feeling in the moment captured by the image. What do they want? What are they hoping for or worried about?

A National Park Service map shows where the contraband camps were primarily located. What do you learn about the contrabands from a study of this map?

Resource: Border States

In this letter, President Lincoln explained and defended his decision to overrule Major General John C. Frémont’s 1861 proclamation that had declared the freedom of all enslaved people in Missouri.

Private + confidential

Executive Mansion

Washington, Sept 22, 1861

Hon. O. H. Browning

My dear Sir,

Yours of the 17th is just received; and coming from you, I confess it astonishes me. That you should object to my adhering to a law, which you had assisted in making, and presenting to me, less than a month before, is odd enough.

Your letter surprises me because I was following a law that you helped write just weeks ago. [The 1861 Confiscation Act had been signed by the president on August 6.]

But this is a very small part. Genl. Frémont's proclamation, as to confiscation of property, and the liberation of slaves, is purely political, and not within the range of military law, or necessity. If a commanding General finds a necessity to seize the farm of a private owner, for a pasture, an encampment, or a fortification, he has the right to do so, and to so hold it, as long as the necessity lasts; and this is within military law, because within military necessity. But to say the farm shall no longer belong to the owner, or his heirs forever; and this as well when the farm is not needed for military purposes as when it is, is purely political, without the savor of military law about it.

In military law, a general can seize an enemy’s property, including enslaved people, that has military value. But when a war ends, the property belongs again to the original owner. The general cannot determine what happens to the property in the future, as General Frémont attempted to do in Missouri with his proclamation. That can only be done by Congress. Frémont’s motives were political, not military. He was acting as if he could do whatever he wanted.

And the same is true of slaves. If the General needs them, he can seize them, and use them; but when the need is past, it is not for him to fix their permanent future condition. That must be settled according to laws made by law-makers, and not by military proclamations. The proclamation in the point in question, is simply ``dictatorship.'' It assumes that the general may do anything he pleases---confiscate the lands and free the slaves of loyal people, as well as of disloyal ones.

The 1861 Confiscation Act allowed the federal government to seize property, including slaves, being used to support the Confederate rebellion. It did not apply to Missouri, a border state that remained loyal to the Union.

And going the whole figure I have no doubt would be more popular with some thoughtless people, than that which has been done! But I cannot assume this reckless position; nor allow others to assume it on my responsibility. You speak of it as being the only means of saving the government. On the contrary it is itself the surrender of the government. Can it be pretended that it is any longer the government of the U.S.—any government of Constitution and laws—wherein a General, or a President, may make permanent rules of property by proclamation? . . .

I do not say Congress might not with propriety pass a law, on the point, just such as General Fremont proclaimed. I do not say I might not, as a member of Congress, vote for it. What I object to, is, that I as President, shall expressly or impliedly seize and exercise the permanent legislative functions of the government.

I know that some people want full emancipation and that you think it’s the only way to save the government. I think it would be the end of the government if a general or a president could issue permanent rules related to property. Congress might do that one day, and I might support it. But the president cannot assume powers that belong to Congress.

So much as to principle. Now as to policy. No doubt the thing was popular in some quarters, and would have been more so if it had been a general declaration of emancipation. The Kentucky Legislature would not budge till that proclamation was modified; and Gen. Anderson telegraphed me that on the news of Gen. Fremont having actually issued deeds of manumission, a whole company of our Volunteers threw down their arms and disbanded. I was so assured, as to think it probable, that the very arms we had furnished Kentucky would be turned against us. I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor, as I think, Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol.

The Kentucky legislature demanded that Frémont’s proclamation be modified. And some Kentucky soldiers were so upset by the proclamation that they refused to fight for the union. If we lose Kentucky, we’ll lose Missouri and probably Maryland. We can’t win if they turn against us.

"Abraham Lincoln to O.H. Browning", 22 September 1861, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1973, vol. 4, 531–534.

Private + confidential

Executive Mansion

Washington, Sept 22, 1861

Hon. O. H. Browning

My dear Sir,

Yours of the 17th is just received; and coming from you, I confess it astonishes me. That you should object to my adhering to a law, which you had assisted in making, and presenting to me, less than a month before, is odd enough.

But this is a very small part. Genl. Frémont's proclamation, as to confiscation of property, and the liberation of slaves, is purely political, and not within the range of military law, or necessity. If a commanding General finds a necessity to seize the farm of a private owner, for a pasture, an encampment, or a fortification, he has the right to do so, and to so hold it, as long as the necessity lasts; and this is within military law, because within military necessity. But to say the farm shall no longer belong to the owner, or his heirs forever; and this as well when the farm is not needed for military purposes as when it is, is purely political, without the savor of military law about it.

And the same is true of slaves. If the General needs them, he can seize them, and use them; but when the need is past, it is not for him to fix their permanent future condition. That must be settled according to laws made by law-makers, and not by military proclamations. The proclamation in the point in question, is simply ``dictatorship.'' It assumes that the general may do anything he pleases---confiscate the lands and free the slaves of loyal people, as well as of disloyal ones.

And going the whole figure I have no doubt would be more popular with some thoughtless people, than that which has been done! But I cannot assume this reckless position; nor allow others to assume it on my responsibility. You speak of it as being the only means of saving the government. On the contrary it is itself the surrender of the government. Can it be pretended that it is any longer the government of the U.S.—any government of Constitution and laws—wherein a General, or a President, may make permanent rules of property by proclamation? . . .

I do not say Congress might not with propriety pass a law, on the point, just such as General Fremont proclaimed. I do not say I might not, as a member of Congress, vote for it. What I object to, is, that I as President, shall expressly or impliedly seize and exercise the permanent legislative functions of the government.

So much as to principle. Now as to policy. No doubt the thing was popular in some quarters, and would have been more so if it had been a general declaration of emancipation. The Kentucky Legislature would not budge till that proclamation was modified; and Gen. Anderson telegraphed me that on the news of Gen. Fremont having actually issued deeds of manumission, a whole company of our Volunteers threw down their arms and disbanded. I was so assured, as to think it probable, that the very arms we had furnished Kentucky would be turned against us. I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor, as I think, Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol.

"Abraham Lincoln to O.H. Browning", 22 September 1861, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1973, vol. 4, 531–534.

With no federal policy to govern the treatment of the formerly enslaved people who arrived behind Union lines, individual officers made their own decisions. A few returned them to slaveholders. Most sheltered them. Major General John C. Frémont, leader of Union forces in Missouri, took a bold step without consulting President Lincoln. In late August 1861, he issued a proclamation that declared martial law in the state, directed Union troops to seize property of Confederates, and permanently freed any enslaved people who were taken under this order. The entire proclamation was printed in Harper’s Weekly, August 31, 1861.

Staunch antislavery Northerners were thrilled, but President Lincoln was not. He asked Frémont to modify the emancipation language in his proclamation to align with the 1861 Confiscation Act. This act, which was rarely enforced, allowed the emancipation of enslaved people who were serving a military purpose for the Confederacy. But Frémont had declared the freedom of all slaves in Missouri, a border state not covered by the 1861 act. On September 11, after Frémont refused to alter his proclamation, Lincoln overruled it.

For Lincoln, at first, the purpose of the war was to keep the United States united, not to end slavery. He believed that antislavery measures would cost him the support of the slave states that had remained within the Union—Missouri, Kentucky, Delaware, and Maryland. They were called the border states because they formed a geographic boundary between the Union and the Confederacy. Their populations were mixed—supporters of slavery, supporters of abolition, Republicans, Democrats—and their loyalties were divided. They had tried to remain neutral, but under pressure from the North, they stayed within the Union. In the map, they are identified as Union states that allowed slavery. (West Virginia joined this group after it formed as a separate state in 1863.) The border states remained on the Union side throughout the war.

Lincoln received more letters about his handling of Frémont’s proclamation than about any other event in his presidency. Some writers were pleased, others furious. On September 17, one of Lincoln’s oldest friends, Senator Orville H. Browning of Illinois, wrote a letter that began, “I greatly regret the order modifying Genl Fremont’s proclamation.” Lincoln was irritated—and surprised. Browning was a conservative Republican, normally very cautious in dealing with political issues. But here he aligned with Radical Republicans who demanded immediate action against slavery. Lincoln quickly wrote this response to explain and defend his thinking.

Despite the positions taken by the two men in September 1861, within months the president came to support emancipation and Senator Browning to reject it. Their friendship continued to sour.

The map is contemporary, included to show why the border states were so important.

- budge

To make a small movement, or to give in slightly.

- confiscation

The act of taking or seizing property by an authority, like a government or military commander.

- deeds of manumission

Documents that prove an enslaved person has been legally freed.

- encampment

A place for soldiers to live temporarily, often in tents.

- policy

A plan or course of action followed by a government or organization.

- proclamation

An official public announcement.

- propriety

Conforming to accepted rules or standards.

- Radical Republicans

Republicans, including many members of Congress, who were fierce abolitionists.

Why was Frémont’s proclamation important? Why did Lincoln overrule it?

What role did the border states play in Lincoln’s thinking?

Why did Lincoln accuse Frémont of dictatorship? What did he mean?

Research the history of Missouri as a slaveholding state. Based on this history, why did Lincoln think Frémont’s proclamation could drive Missouri and other border states to the Confederacy?

Resource: Congress Takes Action

This collection of materials explores the actions that Congress began to take in 1862 to push for emancipation.

SEC. 9. And be it further enacted, That all slaves of persons who shall hereafter be engaged in rebellion against the government of the United States, or who shall in any way give aid or comfort thereto, escaping from such persons and taking refuge within the lines of the army; and all slaves captured from such persons or deserted by them and coming under the control of the government of the United States; and all slaves of such person found on [or] being within any place occupied by rebel forces and afterwards occupied by the forces of the United States, shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves.

Enslaved people who come under Union control will be free forever, if their slaveholders are in rebellion, or are aiding in the rebellion, against the United States.

SEC. 10. And be it further enacted, That no slave escaping into any State, Territory, or the District of Columbia, from any other State, shall be delivered up, or in any way impeded or hindered of his liberty, except for crime, or some offence against the laws, unless the person claiming said fugitive shall first make oath that the person to whom the labor or service of such fugitive is alleged to be due is his lawful owner, and has not borne arms against the United States in the present rebellion, nor in any way given aid and comfort thereto; and no person engaged in the military or naval service of the United States shall, under any pretence whatever, assume to decide on the validity of the claim of any person to the service or labor of any other person, or surrender up any such person to the claimant, on pain of being dismissed from the service.

Enslaved people who escape to Union territory will be free unless they have committed a crime or their slaveholder can prove he or she is not part of the rebellion. No member of the US armed forces can return an escaped enslaved person to a person claiming to be the slaveholder.

SEC. 11. And be it further enacted, That the President of the United States is authorized to employ as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary and proper for the suppression of this rebellion, and for this purpose he may organize and use them in such manner as he may judge best for the public welfare.

The president may employ African Americans to suppress the rebellion in whatever way seems best to end the war.

The Second Confiscation Act. Approved July 17, 1862.

SEC. 9. And be it further enacted, That all slaves of persons who shall hereafter be engaged in rebellion against the government of the United States, or who shall in any way give aid or comfort thereto, escaping from such persons and taking refuge within the lines of the army; and all slaves captured from such persons or deserted by them and coming under the control of the government of the United States; and all slaves of such person found on [or] being within any place occupied by rebel forces and afterwards occupied by the forces of the United States, shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves.

SEC. 10. And be it further enacted, That no slave escaping into any State, Territory, or the District of Columbia, from any other State, shall be delivered up, or in any way impeded or hindered of his liberty, except for crime, or some offence against the laws, unless the person claiming said fugitive shall first make oath that the person to whom the labor or service of such fugitive is alleged to be due is his lawful owner, and has not borne arms against the United States in the present rebellion, nor in any way given aid and comfort thereto; and no person engaged in the military or naval service of the United States shall, under any pretence whatever, assume to decide on the validity of the claim of any person to the service or labor of any other person, or surrender up any such person to the claimant, on pain of being dismissed from the service.

SEC. 11. And be it further enacted, That the President of the United States is authorized to employ as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary and proper for the suppression of this rebellion, and for this purpose he may organize and use them in such manner as he may judge best for the public welfare.

The Second Confiscation Act. Approved July 17, 1862.

SEC. 12. And be it further enacted, That the President be, and he is hereby, authorized to receive into the service of the United States, for the purpose of constructing intrenchments, or performing camp service or any other labor, or any military or naval service for which they may be found competent, persons of African descent, and such persons shall be enrolled and organized under such regulations, not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws, as the President may prescribe.

The president is authorized to enlist African Americans in the armed services to perform either labor or military service.

SEC. 13. And be it further enacted, That when any man or boy of African descent, who by the laws of any State shall owe service or labor to any person who, during the present rebellion, has levied war or has borne arms against the United States, or adhered to their enemies by giving them aid and comfort, shall render any such service as is provided for in this act, he, his mother and his wife and children, shall forever thereafter be free, any law, usage, or custom whatsoever to the contrary notwithstanding: Provided, That the mother, wife and children of such man or boy of African descent shall not be made free by the operation of this act except where such mother, wife or children owe service or labor to some person who, during the present rebellion, has borne arms against the United States or adhered to their enemies by giving them aid and comfort.

The families of formerly enslaved men who serve in the armed forces shall be free unless they have fought with or aided the Confederacy.

The Militia Act. Approved July 17, 1862.

SEC. 12. And be it further enacted, That the President be, and he is hereby, authorized to receive into the service of the United States, for the purpose of constructing intrenchments, or performing camp service or any other labor, or any military or naval service for which they may be found competent, persons of African descent, and such persons shall be enrolled and organized under such regulations, not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws, as the President may prescribe.

SEC. 13. And be it further enacted, That when any man or boy of African descent, who by the laws of any State shall owe service or labor to any person who, during the present rebellion, has levied war or has borne arms against the United States, or adhered to their enemies by giving them aid and comfort, shall render any such service as is provided for in this act, he, his mother and his wife and children, shall forever thereafter be free, any law, usage, or custom whatsoever to the contrary notwithstanding: Provided, That the mother, wife and children of such man or boy of African descent shall not be made free by the operation of this act except where such mother, wife or children owe service or labor to some person who, during the present rebellion, has borne arms against the United States or adhered to their enemies by giving them aid and comfort.

The Militia Act. Approved July 17, 1862.

Throughout the Civil War, the Republican Party—Abraham Lincoln’s party—controlled both houses of Congress. But the Republicans were divided on the crucial issue of slavery. Moderates dominated in Congress and opposed immediate action against slavery. Others, known as Radical Republicans, were abolitionists. There were also Radical Republicans outside the halls of Congress, including Frederick Douglass and newspaper publisher Horace Greeley. Within Congress, the most radical of the Radicals was Thaddeus Stevens, a member of the House of Representatives from Pennsylvania. On the Senate side, the leading Radical Republican was Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. From the earliest days of the war, they pushed for a more aggressive military effort, for enlisting Black soldiers in the all-white Union Army, and for emancipation.

In 1861 and 1862, the North suffered important battlefield defeats, and Lincoln avoided the issue of slavery. Frustrated and angry, Congress began to take action. In August 1861, it passed the first Confiscation Act. This permitted Union forces to seize property, including enslaved people, being used to aid the Confederacy’s military effort. Lincoln signed the bill grudgingly because it applied both to the border states, whose loyalty he needed, and the Confederacy. The law did not apply to the large majority of contrabands, because they were not engaged in work for the Confederate military. So it did little other than restate what was already established in international rules of war. But it signaled that Congress was looking for a path to emancipation.

The Second Confiscation Act and the Militia Act were further evidence of congressional determination to press for abolition and Black enlistment.

Given the limitations of the 1861 Confiscation Act, Congress tried again, with a bill introduced by Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois. But it became ensnared in the divisions that ran through the Republican Party. After months, a compromise was suggested by John Sherman, a House member from Ohio, and this bill passed both houses of Congress. Known as the Second Confiscation Act, it freed enslaved people held by Confederates in Union-held territory.

President Lincoln signed the act into law on July 17, 1862, although his administration made little effort to enforce it. On the same day, he signed the Militia Act, which established a draft to add more troops to the Union forces. It also allowed the president to employ African Americans in any role he deemed necessary to helping the war effort. This opened the door to recruiting Black soldiers.

Five days later, Lincoln presented his cabinet with the first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. It was a more modest statement than Congress had wanted, but as Lincoln worked on later versions of his proclamation, he came more into agreement with the positions of Congress.

- adhered

Agreed with, or supported.

- alleged

Supposed, or claiming to be.

- claimant

A person claiming ownership.

- confiscation

Seizure, or taking.

- hindered

Obstructed, or got in the way.

- impeded

Delayed, or obstructed.

- intrenchments

A trench system to provide shelter from military attack; often spelled entrenchments.

- levied

Engaged in.

- notwithstanding

Despite.

Why was Congress passing these laws? What was it trying to accomplish?

What was the importance of the Radical Republicans in 1861 and 1862?

What was new in the Second Confiscation Act and the Militia Act?

Compare these congressional actions to "The Slavery Question,” published in Harper’s Weekly on July 6, 1862. How did steps taken in Congress align with what Harper’s editors wanted?

Use these resources with the resources in Contrabands and Border States to analyze the conflicting pressures Lincoln faced concerning emancipation during 1861 and 1862.

Research the life of Thaddeus Stevens. How did his background prepare him for the actions he took during the Civil War? What role did he play in events after the war ended?

Resource: The Evolving Language of the Emancipation Proclamation

The three versions of the Emancipation Proclamation that Lincoln wrote show shifts in his approach to abolition.

July 22, 1862

I hereby make known that it is my purpose, upon the next meeting of congress, to again recommend the adoption of a practical measure for tendering pecuniary aid to the free choice or rejection, of any and all States which may then be recognizing and practically sustaining the authority of the United States, and which may then have voluntarily adopted, or thereafter may voluntarily adopt, gradual abolishment of slavery within such State or States---that the object is to practically restore, thenceforward to be maintain[ed], the constitutional relation between the general government, and each, and all the states, wherein that relation is now suspended, or disturbed; and that, for this object, the war, as it has been, will be, prossecuted. And, as a fit and necessary military measure for effecting this object, I, as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, do order and declare that on the first day of January in the year of Our Lord one thousand, eight hundred and sixtythree, all persons held as slaves within any state or states, wherein the constitutional authority of the United States shall not then be practically recognized, submitted to, and maintained, shall then, thenceforward, and forever, be free.

as first sketched and shown to the Cabinet in July 1862.

At the next session of Congress, I will recommend a measure to pay any state that recognizes the authority of the United States and pledges to gradually abolish slavery. The goal is to restore all states to the Union. To accomplish this goal, I, as commander in chief, declare that on January 1, 1863, all enslaved people in Confederate states will be, and remain forever, free.

[The president was trying to persuade the border states to end slavery on their own, gradually.]

Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Springfield, Il.: Abraham Lincoln Association, 1953. 5:336-7.

July 22, 1862

I hereby make known that it is my purpose, upon the next meeting of congress, to again recommend the adoption of a practical measure for tendering pecuniary aid to the free choice or rejection, of any and all States which may then be recognizing and practically sustaining the authority of the United States, and which may then have voluntarily adopted, or thereafter may voluntarily adopt, gradual abolishment of slavery within such State or States---that the object is to practically restore, thenceforward to be maintain[ed], the constitutional relation between the general government, and each, and all the states, wherein that relation is now suspended, or disturbed; and that, for this object, the war, as it has been, will be, prossecuted. And, as a fit and necessary military measure for effecting this object, I, as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, do order and declare that on the first day of January in the year of Our Lord one thousand, eight hundred and sixtythree, all persons held as slaves within any state or states, wherein the constitutional authority of the United States shall not then be practically recognized, submitted to, and maintained, shall then, thenceforward, and forever, be free.

as first sketched and shown to the Cabinet in July 1862.

Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Springfield, Il.: Abraham Lincoln Association, 1953. 5:336-7.

September 22, 1862

That it is my purpose, upon the next meeting of Congress to again recommend the adoption of a practical measure tendering pecuniary aid to the free acceptance or rejection of all slave-states, so called, the people whereof may not then be in rebellion against the United States, and which states, may then have voluntarily adopted, or thereafter may voluntarily adopt, immediate, or gradual abolishment of slavery within their respective limits; and that the effort to colonize persons of African descent, with their consent, upon this continent, or elsewhere, with the previously obtained consent of the Governments existing there, will be continued.

That on the first day of January in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any state, or designated part of a state, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

At the next session of Congress, I will recommend a measure to pay any state that recognizes the authority of the United States and pledges to voluntarily abolish slavery, immediately or over time. The effort to encourage free African Americans to move to colonies outside the US will continue. On January 1, 1863, all enslaved people in Confederate states will be, and will forever remain, free. The federal government will recognize and maintain their freedom and will not repress them.

Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Springfield, Il.: Abraham Lincoln Association, 1953. 5:433-6.

September 22, 1862

That it is my purpose, upon the next meeting of Congress to again recommend the adoption of a practical measure tendering pecuniary aid to the free acceptance or rejection of all slave-states, so called, the people whereof may not then be in rebellion against the United States, and which states, may then have voluntarily adopted, or thereafter may voluntarily adopt, immediate, or gradual abolishment of slavery within their respective limits; and that the effort to colonize persons of African descent, with their consent, upon this continent, or elsewhere, with the previously obtained consent of the Governments existing there, will be continued.

That on the first day of January in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any state, or designated part of a state, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Springfield, Il.: Abraham Lincoln Association, 1953. 5:433-6.

January 1, 1863

By the President of the United States of America:

A Proclamation.

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

"That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

On September 22, 1862, in the preliminary proclamation, the president declared that all enslaved people in the rebelling states—the Confederacy—would, as of January 1, 1863, be forever free.

"That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States."

The preliminary proclamation indicated that the president would name the states in rebellion on January 1, 1863. Any state represented in the US Congress is considered not to be in rebellion against the United States.

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Therefore today I, Abraham Lincoln, as commander in chief of the army and navy, take this necessary step to suppress the rebellion. One hundred days ago, on September 22, I declared publicly that I would take this action.

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

These are the states currently in rebellion. Areas in parentheses are in Union hands and therefore exempt from this proclamation.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

I declare that all enslaved people in the rebelling states or parts of states mentioned above are now free. The federal government will recognize and maintain their freedom and will not repress them.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

I direct all freed people to refrain from violence unless in self-defense, and I ask them to work dependably for reasonable pay.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

Freed men, if they are healthy, can now join the US military to guard forts and other locations and to serve on ships.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

I hope that God and man will see this as an act of justice based on military need.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

By the President: ABRAHAM LINCOLN

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

I have signed this proclamation on January 1, 1863, the 87th year of American independence.

Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Springfield, Il.: Abraham Lincoln Association, 1953. 6:28-30.

January 1, 1863

By the President of the United States of America:

A Proclamation.

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

"That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

"That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States."

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

By the President: ABRAHAM LINCOLN

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Springfield, Il.: Abraham Lincoln Association, 1953. 6:28-30.

From the beginning of Lincoln’s presidency, abolitionists and fellow Republicans in Congress pressed him to take direct action against slavery. He resisted, over and over. He did not believe he had the authority to do so, because slavery was protected by the US Constitution and by state laws. He also thought it would alienate the border states that he needed on his side. He was focused on ending the rebellion and saving the Union.

But in the early months of the war, Union victory proved elusive. A major reason was the more than three million enslaved people in the South. Lincoln recognized that this workforce gave the enemy an overwhelming military advantage. At the same time, hundreds, eventually thousands, of men, women, and children began to escape slavery and seek safety behind Union lines. Called contrabands, they worked in many capacities and provided valuable service to the Union Army.

Initially, contrabands were viewed as a problem. But Lincoln came to see that if he declared their freedom, many more enslaved people would seek the safety of Union-held territory. This would hurt the Confederacy and help the North. Moreover, the Union needed Black manpower in its military forces. And because his country was at war, taking steps against the enemy was within his power as commander in chief. His authority did not extend to areas that were not at war with the United States, so his action would not apply in the border states, which allowed slavery but remained in the Union.

Beginning in the spring of 1862, Abraham Lincoln wrote three versions of the Emancipation Proclamation. The first draft was short and unpolished. It called for paying border states to gradually end slavery and for freeing enslaved people in the Confederacy as of January 1, 1863. The president shared this draft with his cabinet in July. Secretary Seward and others advised the president to wait for a military victory before making the proclamation public. Lincoln agreed.

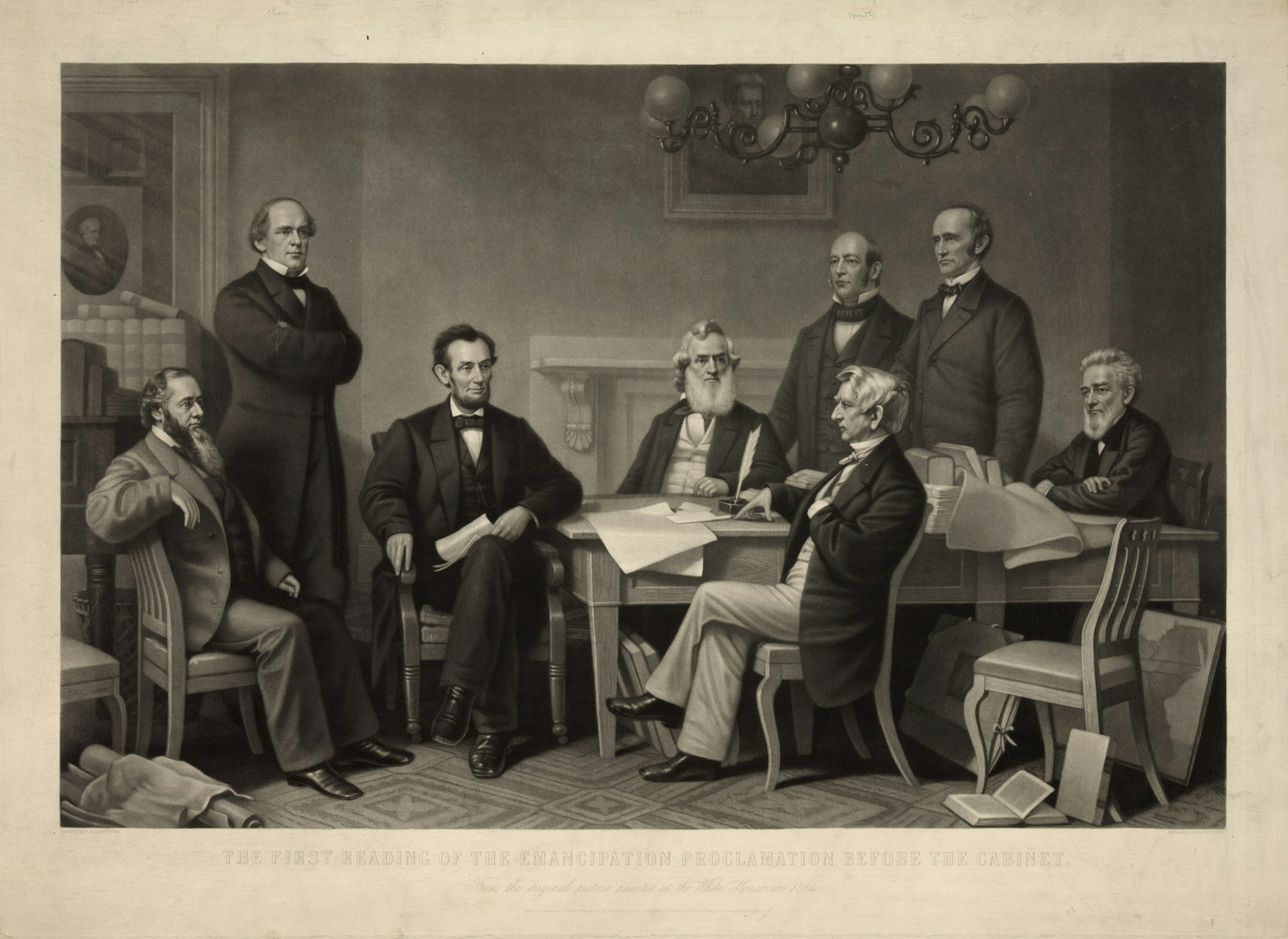

The lithograph, “President Lincoln presents the first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation to his Cabinet,” captures the meeting when members of Lincoln’s cabinet heard the earliest version of the proclamation. From left to right: Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War; Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of the Treasury; President Lincoln; Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy; Caleb B. Smith, Secretary of the Interior; William H. Seward, Secretary of State; Montgomery Blair, Postmaster General; and Edward Bates, Attorney General.

After a modest Union victory at Antietam in September 1862, Lincoln published another version (the preliminary emancipation proclamation). It was longer and more formally written than the earlier draft. But like the first version, it set January 1, 1863 as the day most enslaved people in the Confederacy would be free, and it encouraged the border states to gradually end slavery. To make it more appealing to white Southerners, who did not wish to see a large new population of free Black people created, it proposed establishing colonies outside the United States where freed people could resettle voluntarily. Lincoln thought gradual emancipation and colonization would calm the fears of those who might otherwise see the proclamation as too extreme.

President Lincoln signed the third and final version of the Emancipation Proclamation just before New Year’s Day, 1863. Like the previous drafts, it declared most enslaved people in the Confederacy to be forever free as of that date. But it differed in important ways from the earlier versions. It eliminated both colonization and gradual emancipation with the promise of monetary compensation to owners, and it added a momentous new clause: African American soldiers would be welcomed into the United States armed services for the first time. In addition, unlike the Confiscation Acts, it did not make a distinction between enslaved people of Confederates and those of owners loyal to the Union—all enslaved people in affected areas would be freed.

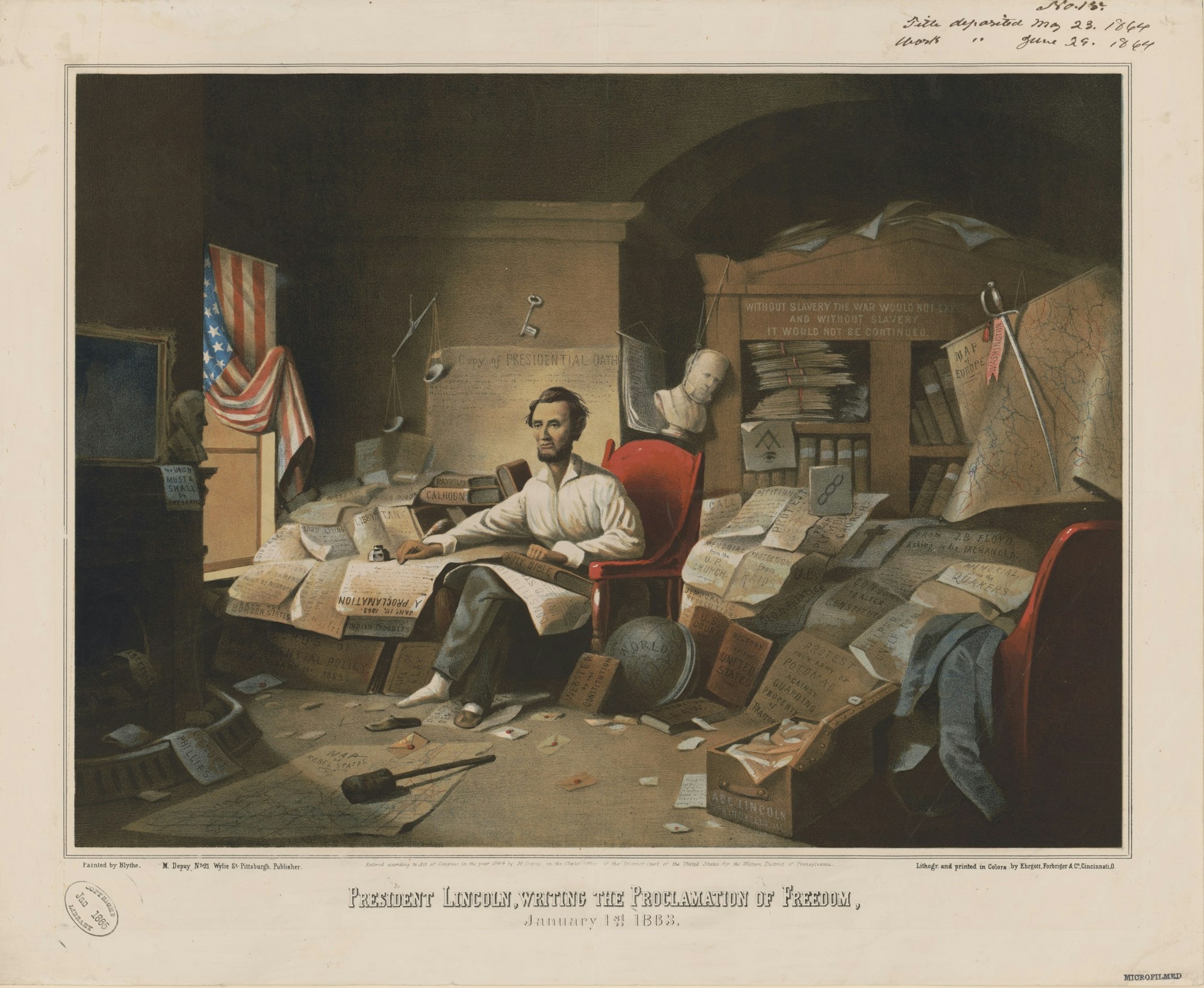

Many of Lincoln’s critics in both the North and the South opposed emancipation and thought the president was abusing his power. The lithograph entitled “President Lincoln, writing the Proclamation of Freedom” may have been meant to bolster support for the president, who was in real danger of losing the 1864 election. The image is rich with symbols associated with the nation and the righteousness of emancipation. An American flag half-covers the open window. George Washington’s sword sticks out of a map of Europe on the right wall. A bust of President Andrew Jackson, a strong Unionist, sits on the mantelpiece. A bust of President James Buchanan, who did not take action against the seceding states before Lincoln’s inauguration, dangles in a noose on the bookcase. The image portrays a disheveled Lincoln putting his all into the creation of this document. He draws inspiration from the Bible and the Constitution. Behind him hang the scales of justice, and a rail-splitter’s maul near his feet evokes his country origins.

- aforesaid

Mentioned before.

- border states

States that remained in the Union but permitted slavery. The border states were Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. West Virginia became a border state after it formed in 1863.

- countervailing

Conflicting.

- effecting this object

Accomplishing this goal.

- Executive

The president.

- Executive Government

The federal government.

- lithograph

A printed picture made by a special process popular since the 19th century.

- proclamation

An official announcement.

- prossecuted

Old spelling of prosecuted, meaning pursued to the end.

- tendering pecuniary aid

Providing money.

- thenceforward

From then on.

- thereafter

After that.

- thereof

Of that.

- thereto

To that place.

- to wit

Namely, or specifically.

- whereas

In view of the fact that.

During 1861 and early 1862, what was Lincoln’s main priority in the war? How did it prevent him from acting to end slavery?

Why did Lincoln think he had to make a choice between saving the Union and ending slavery?

What made Lincoln change his mind and issue the Emancipation Proclamation?

The US Constitution grants Congress the power to declare war. It grants a different authority to the president: The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States. Presidents and Congress have grappled with, and often disagreed over, this distinction. What do you think it means to be commander in chief? How did President Lincoln use this power during the Civil War? How did President Harry Truman (Unit 1) and President George W. Bush (Unit 2) interpret their authority as president during wartime? How has the meaning of commander in chief changed over time?

Compare the Second Confiscation Act and the Militia Act to the Final Emancipation Proclamation. What similarities and differences do you see? What made the presidential proclamation significant?

Research the negative reactions to the Emancipation Proclamation in the North and in the South. What did Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States, think? What was the reaction of Northern Democrats who opposed the Civil War? What did these opponents of Lincoln’s proclamation think would be its result?

Resource: Frederick Douglass Responds

Two documents explore Frederick Douglass’s response to Lincoln’s views on emancipation.

Common sense, the necessities of the war, to say nothing of the dictation of justice and humanity have at last prevailed. We shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree. Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, Commander-in-Chief of the army and navy, in his own peculiar, cautious, forbearing and hesitating way, slow, but we hope sure, has, while the loyal heart was near breaking with despair, proclaimed and declared: ‘That on the First of January, in the Year of Our Lord One Thousand, Eight Hundred and Sixty-three, All Persons Held as Slaves Within Any State or Any Designated Part of a State, The People Whereof Shall Then be in Rebellion Against the United States, Shall be Thenceforward and Forever Free.’…

At last, we are able to celebrate President Lincoln’s proclamation of emancipation in the Confederate states.

Opinions will widely differ as to the practical effect of this measure upon the war. All that class at the North who have not lost their affection for slavery will regard the measure as the very worst that could be devised, and as likely to lead to endless mischief. All their plans for the future have been projected with a view to a reconstruction of the American Government upon the basis of compromise between slaveholding and non-slaveholding States. The thought of a country unified in sentiments, objects and ideas, has not entered into their political calculations, and hence this newly declared policy of the Government, which contemplates one glorious homogeneous people, doing away at a blow with the whole class of compromisers and corrupters, will meet their stern opposition. Will that opposition prevail? Will it lead the President to reconsider and retract?

Northerners who are pro-slavery will not approve of the Emancipation Proclamation. They have expected that slavery would continue in some states after the war. They will oppose the proclamation.

Not a word of it. Abraham Lincoln may be slow, Abraham Lincoln may desire peace even at the price of leaving our terrible national sore untouched, to fester on for generations, but Abraham Lincoln is not the man to reconsider, retract and contradict words and purposes solemnly proclaimed over his official signature.

The careful, and we think, the slothful deliberation which he has observed in reaching this obvious policy, is a guarantee against retraction. . . .

But President Lincoln will not change his mind. He was slow to act, and he wanted national union more than he wanted to end slavery. But now he has given his word, and he can be trusted.

Now let the Government go forward in its mission of Liberty as the only condition of peace and union. . . . Let only the men who assent heartily to the wisdom and the justice of the anti-slavery policy of the Government be lifted into command; let the black man have an arm as well as a heart in this war, and the tide of battle which has thus far only waved backward and forward, will steadily set in our favor.

From now on, ending slavery is the purpose of the war. Only people who agree to this should be in command of the military. And if Black men are allowed to fight, we will start to win the war.

Frederick Douglass, “Emancipation Proclaimed,” Douglass’ Monthly, October 1862. Reprinted in The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Vol. III: The Civil War, 1861–1865, Philip S. Foner, ed. New York: International Publishers, 1952.

Common sense, the necessities of the war, to say nothing of the dictation of justice and humanity have at last prevailed. We shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree. Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, Commander-in-Chief of the army and navy, in his own peculiar, cautious, forbearing and hesitating way, slow, but we hope sure, has, while the loyal heart was near breaking with despair, proclaimed and declared: ‘That on the First of January, in the Year of Our Lord One Thousand, Eight Hundred and Sixty-three, All Persons Held as Slaves Within Any State or Any Designated Part of a State, The People Whereof Shall Then be in Rebellion Against the United States, Shall be Thenceforward and Forever Free.’…

Opinions will widely differ as to the practical effect of this measure upon the war. All that class at the North who have not lost their affection for slavery will regard the measure as the very worst that could be devised, and as likely to lead to endless mischief. All their plans for the future have been projected with a view to a reconstruction of the American Government upon the basis of compromise between slaveholding and non-slaveholding States. The thought of a country unified in sentiments, objects and ideas, has not entered into their political calculations, and hence this newly declared policy of the Government, which contemplates one glorious homogeneous people, doing away at a blow with the whole class of compromisers and corrupters, will meet their stern opposition. Will that opposition prevail? Will it lead the President to reconsider and retract?

Not a word of it. Abraham Lincoln may be slow, Abraham Lincoln may desire peace even at the price of leaving our terrible national sore untouched, to fester on for generations, but Abraham Lincoln is not the man to reconsider, retract and contradict words and purposes solemnly proclaimed over his official signature.

The careful, and we think, the slothful deliberation which he has observed in reaching this obvious policy, is a guarantee against retraction. . . .

Now let the Government go forward in its mission of Liberty as the only condition of peace and union. . . . Let only the men who assent heartily to the wisdom and the justice of the anti-slavery policy of the Government be lifted into command; let the black man have an arm as well as a heart in this war, and the tide of battle which has thus far only waved backward and forward, will steadily set in our favor.

Frederick Douglass, “Emancipation Proclaimed,” Douglass’ Monthly, October 1862. Reprinted in The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Vol. III: The Civil War, 1861–1865, Philip S. Foner, ed. New York: International Publishers, 1952.

Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery at the age of 20 and became one of the leading abolitionists in America. He did not see the first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation because it was not made public. But he read the preliminary proclamation. Lincoln’s promotion of voluntary colonization, in which free Black people would be encouraged to move to colonies outside the US, infuriated Douglass. He wanted Black people to be free and recognized as true Americans, with every right to remain in their home country. And he wanted the Union Army to accept Black men, so they could fight to end the system that oppressed them and their people. Nevertheless, he praised the preliminary emancipation proclamation when it was issued on September 22, 1862, and published in Northern newspapers.

One hundred days later, Lincoln issued the final Emancipation Proclamation, with historic changes to the text. This document gave Douglass what he had fought for: the promise of freedom for the enslaved in the Confederacy and the right of Black men to fight in the Union Army and Navy. It contained no language about colonization.

Douglass’ Monthly was one of four newspapers Frederick Douglass wrote and published in his lifetime. The Monthly appeared between 1858 and 1863. In the lead article in the September 1862 issue, Douglass railed against colonization, which he called “satanic.” By the time he published the next issue in October, Douglass had read the preliminary emancipation proclamation. He wrote “Emancipation Proclaimed” for the Monthly. Lincoln’s preliminary text did not satisfy all of Douglass’s hopes, but it accomplished what he wanted most: it declared the freedom of the more than three million enslaved people in the Confederate states. It contained language that promoted colonization, but Douglass made no mention of it in this article. He did, fairly gently, argue that Black men should be allowed to fight for the Union. Mostly he celebrated. “Read the proclamation,” he urged, “for it is the most important of any to which the President of the United States has ever signed his name.”

Three months later, Lincoln issued the final Emancipation Proclamation. The new language contained no reference to colonization. Equally significantly, it declared the Union armed forces open to Black men.

Douglass went to work quickly to recruit Black soldiers. “Men of Color, To Arms!” first appeared as a headline in Douglass’ Monthly in early March. The article encouraged Black enlistment in the 54th Massachusetts, the first unit of Black soldiers raised in the North. And then it appeared in newspapers and in bold type on broadsides posted in public spaces in the Northern states. It became the rallying cry for Black recruitment in the North.

Volunteers responded in huge numbers. By mid-May 1863, the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment was full, so a second regiment, the 55th Massachusetts, began accepting new recruits. Other Black regiments began forming around the country, including in Union-held parts of the South.

- broadside

A printed sheet of information.

- class

Group of people.

- dictation

Requirement.

- fester

Worsen, grow more infected.

- homogeneous

Basically alike.

- national sore

A reference to slavery.

- prevailed

Succeeded.

- righteous

Morally correct, virtuous.

- slothful

Slow, lazy.