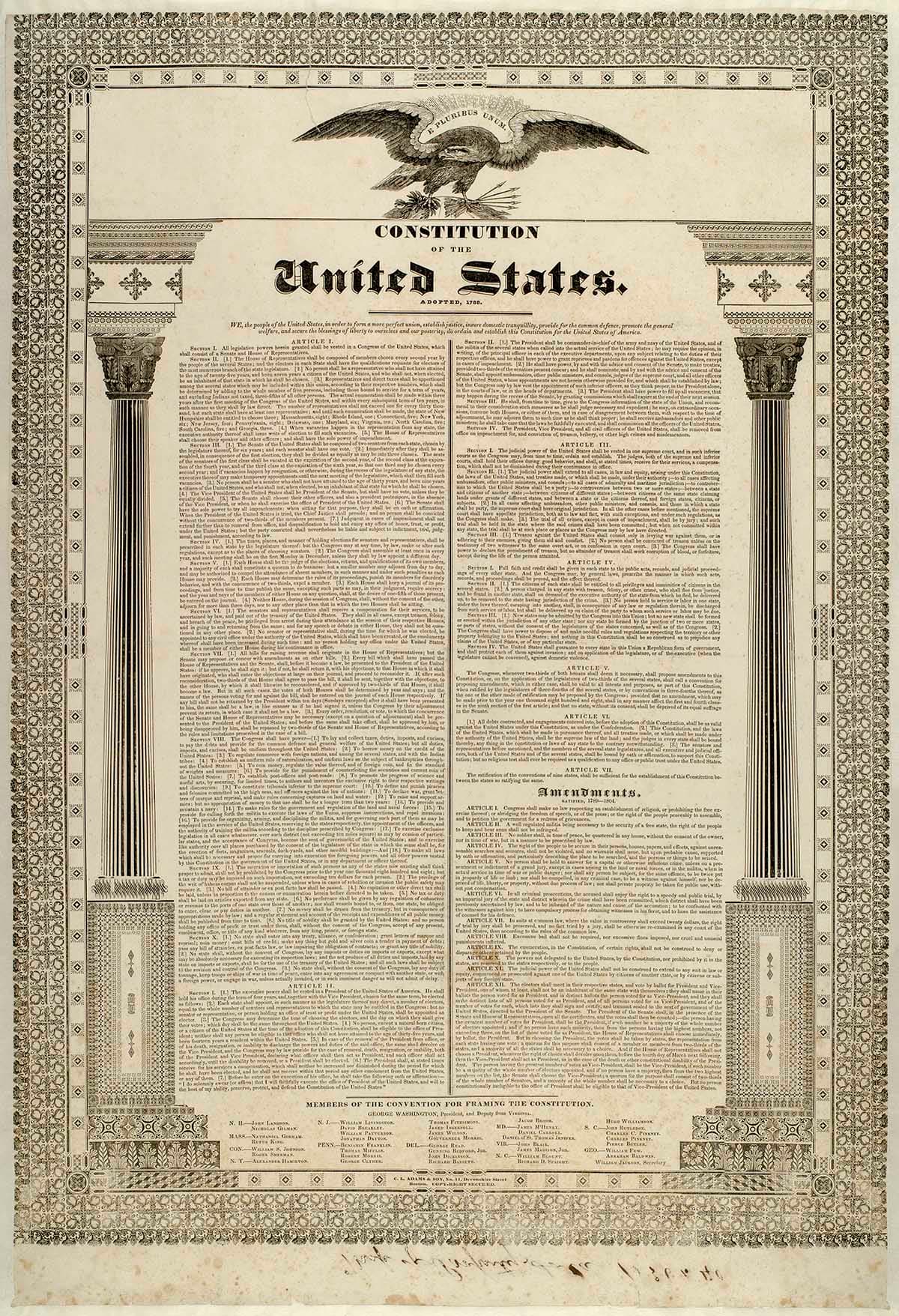

Constitution

Constitution of the United States, ca. 1830s. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

The Constitution provides the framework for the U.S. government. It replaced the earlier Articles of Confederation, which had established a central government too weak to function well. In the Constitution, the founders created an innovative new position—the president. They aimed to give the federal government enough power to do the nation’s work, but not enough to become tyrannical.

To help achieve this, the framers of the Constitution designated three branches of government: legislative, executive, and judicial. The branches are defined as co-equal—not identical but of equal importance. Article I addressed Congress, which the founders assumed would be the center of government. Article II focused on the executive, establishing presidential selection, powers, responsibilities, and removal. Article III created the supreme and lower federal courts. Power is shared among the branches, and no branch can act with complete independence.

Presidential powers are less well defined than those of Congress. They have expanded substantially over two centuries, as presidents have gained political power beyond what the Constitution expressly grants. But the president must still work with Congress to enact legislation, and the exercise of power in both branches is subject to review by the courts.

Oath of Office

“I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of president of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

The language of the oath of office is written in the Constitution and repeated at every presidential inauguration. It is the brief, simple, and profound vow that the president makes to the American people.

Keith Shaw Williams (1906-1951), Inauguration of George Washington at Federal Hall, New York City, 1789, 1938. New-York Historical Society Purchase, General Fund

On April 30, 1789, George Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States at Federal Hall in New York City.

Railing from Federal Hall, 1788-1789. New-York Historical Society, Gift of the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York, 1884.3

Washington chose to take the oath of office outside, on the balcony, so “that the greatest number of people” could witness the event. This is the original center section of the balcony railing of Federal Hall, which had been a municipal building before being transformed by French architect Pierre-Charles L’Enfant into the headquarters of the new national government. L’Enfant's new façade had a classical and patriotic motif; for example, each of the railing’s thirteen arrows represent one of the 13 original states.

Washington’s Inaugural Bible. St. John’s Masonic Lodge, No.1, A.Y.M. Photograph courtesy Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Washington swore the oath with his hand on this Bible, which belonged to the nearby St. John’s Masonic Lodge, No.1, A.Y.M. Since then, other presidents have used the same Bible for their inaugurations, including Warren Harding, Dwight Eisenhower, Jimmy Carter, and George H.W. Bush.

Troops of the 101st Airborne Division escort the Little Rock Nine to Central High School, 1957. U.S. Army

In 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent federal troops to help nine black teenagers begin their studies at a white high school in Little Rock, Arkansas. The Supreme Court had ordered the nation’s schools desegregated in the 1954 ruling Brown v. Board of Education, but Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus refused to admit black students. Eisenhower was not an ardent supporter of integration, but he felt bound by the promise he had made. “When I became President,” he wrote to Faubus, “I took an oath to support and defend the Constitution of the United States. The only assurance I can give you is that the Federal Constitution will be upheld by me by every legal means at my command.”

The oath of office is a brief, simple, and profound vow, written in the Constitution, and repeated verbatim at every inauguration. Each new president pledges to faithfully execute their duties and “preserve, protect, and defend” the Constitution.

In times of uncertainty, the fulfillment of that oath is a reassurance to the American people that the government made by them is working for them. Eisenhower knew this when he sent his telegram to Faubus, and the parents of the Little Rock Nine knew it when they sent Eisenhower a telegram of their own. They thanked him and let him know that his actions “strengthened our faith in democracy now as never before.”

Executive Branch

The Constitution defines the president’s power and duties in broad strokes. George Washington was the first to put them into practice and was keenly aware of his singular place in history. Willing to assert his authority, he was just as willing to acknowledge the office’s constitutional limits. He was a president, not a king.

Presidents exercise their constitutional power through the executive branch. After Washington’s presidency and throughout the 1800s, the executive branch expanded, especially during times of war and economic crisis. In the 1900s, the executive branch grew even more as it attended to social needs, ranging from housing to unemployment.

Today, the branch’s fifteen executive departments and multiple independent agencies help the president and vice-president carry out and enforce the law. George Washington and his advisers could easily meet around a small table. Modern presidents manage a work force larger than the population of Los Angeles.

Unidentified maker, George Washington inaugural armchair, 1788–89. New-York Historical Society, Gift of Edmund B. Southwick

On April 30, 1789, George Washington began his presidency at Federal Hall on Wall Street, the nation’s first capitol (1789–90). He took the oath of office while standing on the building’s balcony, then sat in this mahogany chair before speaking to Congress. Every president since has followed Washington’s lead in delivering an inaugural address to the legislature. His actions established many of the practices and customs of the American presidency.

Washington appointed, and the Senate confirmed, four distinguished colleagues to help him execute the laws of the land. The cabinet included the Attorney General and the Departments of State, Treasury, and War, which shouldered responsibility for justice, foreign relations, economic stability, and national security respectively.

Currier & Ives, Washington and His Cabinet, 1876. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

N. Mendal Shafer, Diagram of the Federal Government of the Great Republic of the United States of America, 1864. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society, Gift of Bella C. Landauer

In 1864, during the Civil War, attorney Noah Mendal Shafer created this stunning diagram in support of maintaining the Union. He wanted to educate Americans about a government system he called “the strongest in the world.” New York City’s Board of Education received its own copy of the diagram.

In the 19th century, the nation’s land area quadrupled through purchase and conquest, and the population grew by many millions. The federal government expanded to provide needed services, especially when the Civil War required thousands of added personnel, and Congress opened federal land to railroads and homesteaders.

On a scale neither Washington nor Lincoln could have imagined, modern presidents manage crises, set the national agenda, and drive policy. Their responsibilities grew substantially after 1900, when the government began attending to Americans’ health and economic welfare. The public generally applauded this governmental role. A new federal income tax helped pay for it.

With the support of Congress, President Franklin Roosevelt greatly enlarged the executive branch during the 1930s and 1940s. Roosevelt added numerous agencies to tackle the emergency of the Great Depression, and he established the Executive Office of the President (EOP) to house the president’s top advisers and political allies. Within the EOP, he created a command center known as the White House Office.

Today, the executive branch employs more than 4 million people. It affects the lives of Americans every day, whether they are buying food, visiting national parks, or browsing the Internet. There are now fifteen executive departments and hundreds of agencies, corporations, and other organizations.

War and Foreign Affairs

The president is both the nation’s commander-in-chief and its leading diplomat, powers assigned by the Constitution. As chief diplomat, the president negotiates treaties and appoints ambassadors with Senate approval. George Washington initiated treaty negotiations with Native nations. Woodrow Wilson represented the United States in the peace conference that followed World War I.

As commander-in-chief, the president exercises civilian control of the US military. Abraham Lincoln used military force in the Civil War, and John Kennedy withheld it during a standoff with Russia. Each was acting in his capacity as commander-in-chief.

Presidents now exercise considerable authority over war and diplomacy on the international stage. It’s the president who most often deploys the military, although Congress has the sole constitutional power to declare war.

George Washington peace medal. National Museum of the American Indian

President George Washington sent a representative to central New York for treaty talks with the sovereign Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy. Some of these Native nations had sided with Britain during the Revolution. Washington hoped to establish friendly relations and secure Haudenosaunee neutrality in ongoing land disputes to the west. The Six Nations looked to protect their people from abusive white settlers and gain recognition of Haudenosaunee sovereignty.

F. Bartoli, Ki On Twog Ky (Also known as Cornplanter, 1732/40–1836), 1796. New-York Historical Society, Gift of Thomas Jefferson Bryan

Washington followed diplomatic protocol in dealing with the Native nations. Before the talks, he sent a tomahawk-pipe to Cornplanter, a Six Nations negotiator. By combining a weapon with a peace pipe, the gift symbolized a turn from war to peace. After months of negotiation, the parties signed the Canandaigua Treaty in 1794.

The Treaty of Canandaigua, 1794. National Archives, Washington, DC

John Rogers, The Council of War, 1868. New-York Historical Society Purchase

President Abraham Lincoln was the nation’s commander-in-chief throughout the Civil War. He conferred regularly with generals and the secretary of war, and often directed military strategy. Lincoln also freed slaves by proclamation, established a draft to put more soldiers in Union blue, and delivered the Gettysburg Address. The speech honored fallen soldiers who had died to ensure that a “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” He also suspended civil rights for those accused of disloyalty.

54th U.S. Colored Troops Infantry Regiment, 1861–65. Library of Congress

The legality and rightness of some of Lincoln’s actions have been debated ever since. Were they unprecedented steps for unprecedented times—or dangerous presidential overreach?

Mathew Brady, Ringgold Battery on drill, 1861–65. National Archives at College Park, MD

World War I poster. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Woodrow Wilson took a 1919 whistle-stop tour to build public support for the Treaty of Versailles, which created the League of Nations. He had just spent months with other leaders in Paris negotiating the end of World War I. Wilson strongly believed the League of Nations could prevent similar destruction and bloodshed in the future.

Congress usually defers to presidents on matters of foreign policy, so Wilson expected Senate approval of the treaty. But Senators were worried that it would compromise congressional authority over war and foreign affairs. In a rare move, the majority voted not to ratify the treaty. The United States never became a member of the League of Nations. But at the end of World War II, it joined the United Nations, which was modeled on the League.

In 1962, New York high school student Marsha Sorotick began a scrapbook about John F. Kennedy’s presidency for a school assignment. Not long after, Kennedy gave an urgent TV address, informing Americans that the Soviet Union had placed nuclear missiles in Cuba within bombing range of US cities. Sorotick’s scrapbook had a serious new focus: “We felt like maybe during the night, they’d blow us up.”

As commander-in-chief, Kennedy could have tried to destroy the missiles with a military strike. Concerned about the risk of nuclear war, he instead asked national security advisers to develop other options. He ordered a naval quarantine to prevent Soviet ships from reaching Cuba, and communicated directly with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. After 13 tense days, the Soviets removed the weapons.

Map used during secret meetings on the Cuban Missile Crisis showing the full range of nuclear missiles under construction in Cuba, 1962. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Domestic Affairs

Presidential responsibilities in domestic affairs are not well defined in the Constitution. Over time, various presidents have helped define and increase presidential powers and duties in this arena. With the Louisiana Purchase, Thomas Jefferson opened the door for future presidents to take actions that exceed their written powers. And ever since Franklin Roosevelt involved the federal government in tackling the Great Depression, the public has expected presidents to have a bold vision and plan for the nation’s future.

Presidential reach has expanded, but no branch of government has unlimited power. Congress can choose to not support a president’s goals. And the president can veto acts passed by Congress, a power Chester Arthur used to modify a bill limiting Chinese immigration. The courts can overrule actions by both the president and Congress, as the Supreme Court did when Richard Nixon sought to keep the Pentagon Papers secret.

President Thomas Jefferson stretched his principles and the power of the presidency when he purchased the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803. Jefferson believed that presidents should only take actions specifically permitted by the Constitution, which did not include buying foreign property. However, he didn’t want to pass up the opportunity to nearly double the size of the United States, so he applied his treaty-making powers. Napoleon was eager to sell, and US ambassadors in Paris negotiated a bargain price of $15 million.

Map showing Louisiana Territory, 1804. Courtesy of Boston Rare Maps

The Senate approved the treaty and freed the funds to purchase the land. The Louisiana Purchase constituted a major incursion by the U.S. onto lands belonging to Indigenous nations. It also contributed to the principle that some presidential powers are implied in the Constitution, rather than stated.

Stafford Mantle Northcote, Tong Yin Yee Shung Gun, Chinese Laundry, 1899. New-York Historical Society, Gift of George A. Zabriskie

Chinese immigrants began arriving in California around 1850, working for low pay to support families at home. Local workers resented them and began “The Chinese Must Go” campaign. In response, Congress passed a bill suspending the immigration of Chinese laborers for 20 years. President Chester Arthur thought the long exclusion period violated the spirit of an existing treaty with China, so he vetoed the bill.

The Chinese Must Go cap pistol, 1879–80. New-York Historical Society, Gift of Marilynn Karp in memory of Ivan C. Karp

Congress lacked the votes to override Arthur’s veto. Instead, lawmakers decreased the suspension period to 10 years and sent the revised bill to the president. More satisfied that it conformed to treaty terms, Arthur signed it. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was America’s first law to restrict immigration based on race. Congress extended and strengthened the law several times before repealing it during World War II.

Enit Zerner Kaufman, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945), ca. 1940–45. New-York Historical Society, Gift of Enit Kaufman

No president has faced a greater economic crisis than Franklin D. Roosevelt. Elected early in the Great Depression, he took immediate steps to create the economic relief and recovery programs known as the New Deal. He worked so effectively with Congress in his first 100 days in office that this period has since become a measure of a president’s early success. Beyond his legislative achievements, Roosevelt connected with the American people, using radio talks to calm fears and inspire confidence.

Unemployed worker outside vacant store, 1935. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum

Roosevelt’s administration changed what Americans expect from the nation’s leader. They want presidents to have ambitious goals and the policy plans to achieve them. They also expect presidents to communicate with the public directly about important goals, decisions, and initiatives.

“Transitone” radio, ca. 1941. New-York Historical Society, Gift of Mary Ann Dzupin Gallagher and Nancy Dzupin York in memory of Anna Varhol Dzupin

Men of the 173rd Airborne Brigade on a search and destroy patrol after receiving supplies, 1966. National Archives at College Park, MD

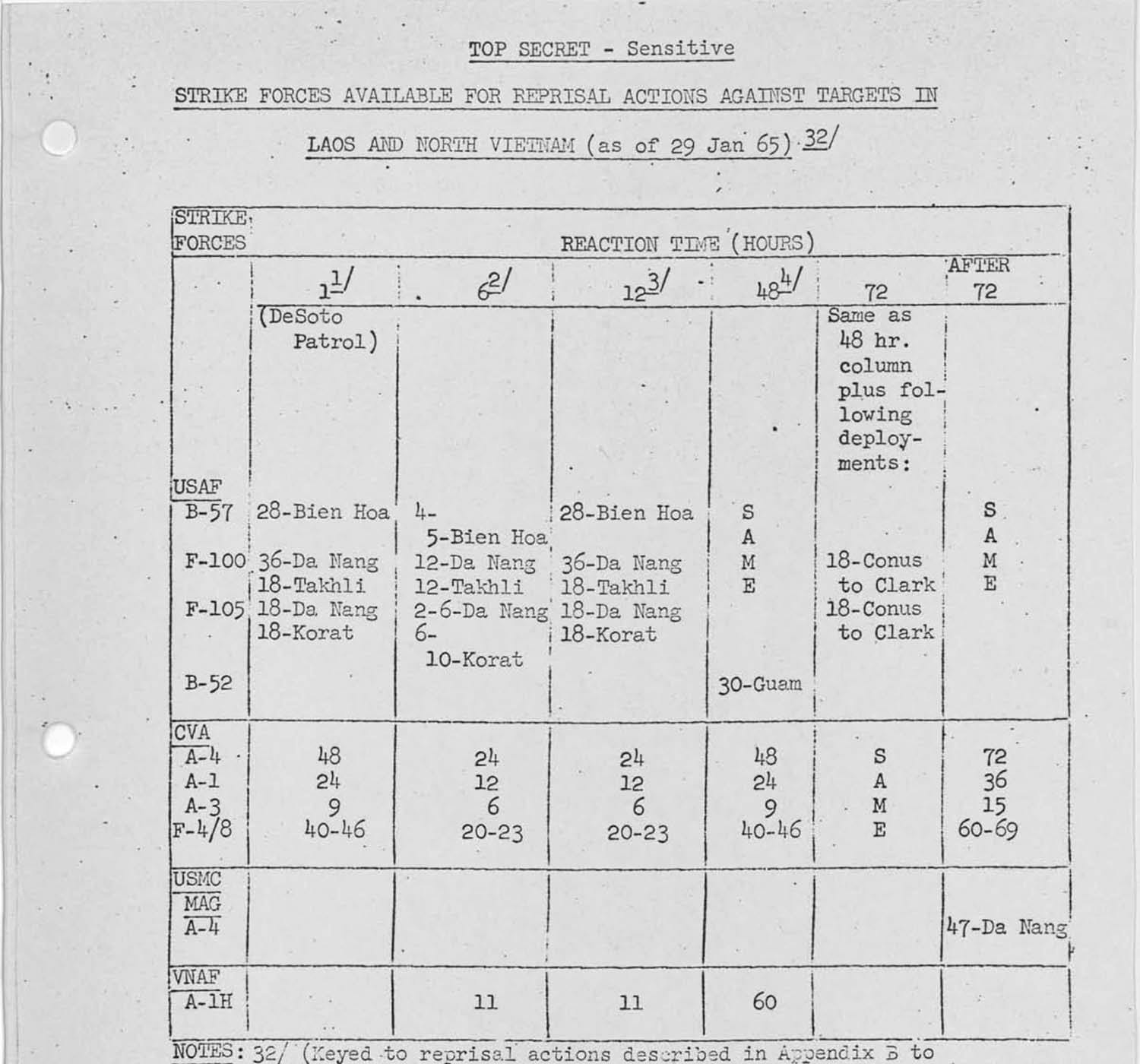

In June 1971, The New York Times and The Washington Post began publishing articles about a top-secret study of the Vietnam War by the Department of Defense. President Richard Nixon’s administration threatened editors with prison and sought an injunction to halt further installments, claiming a risk to national security. The high-stakes episode riveted the nation as it pitted presidential power against freedom of the press.

U.S. District Judge Murray Gurfein, a recent Nixon appointee in New York, denied the injunction, ruling that government officials had not proven their national security claim. The case reached the Supreme Court, which decided against Nixon and confirmed that the president is not above the law. The documents, known as the Pentagon Papers, were published, exposing a decades-long pattern of official duplicity about the war.

Leadership

The presidential ticket is the only one elected by the American people as a whole. So the president is in a singular position of national leadership. Presidents have embraced this role in different ways, depending on their own values and strengths and the challenges they face in office. Nature-lover Theodore Roosevelt, for example, focused on the future when he helped preserve special places for “all who come after.”

Presidents are also the leaders of their party. However, serving both nation and party can be challenging, and leaders must sometimes choose between the two. Lyndon Johnson put national needs first when he supported civil rights legislation that Southern Democrats had condemned.

National leadership is particularly needed when a disaster or tragedy strikes. People expect their president to share feelings of loss, to inspire unity and resolve, and to light a path forward. Technology allows presidents to step into this delicate role quickly. Just six hours after the Challenger space shuttle disaster, Ronald Reagan delivered an eloquent message of consolation on TV.

President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt was transfixed by his first view of the Grand Canyon. He spoke to Americans from that very spot, imploring them to “leave it as it is. You cannot improve it.” Three years later, he signed the 1906 Antiquities Act, which enables presidents to protect archaeological sites by designating them as national monuments. Roosevelt then decided to apply the law more broadly to safeguard areas of historic, scenic, or scientific importance. The Grand Canyon was one of 18 national monuments he set aside for future generations. It was later named a national park.

Grand Canyon. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

Since Roosevelt, most presidents have identified new national monuments under the Antiquities Act. One of the most frequently visited is the Statue of Liberty, designated by Calvin Coolidge in 1924. In 2016, Barack Obama added the Stonewall Inn, noteworthy for its role in the LBGTQ movement.

Listen to a rare recording of Roosevelt talking about leadership in this excerpt of his speech “The Right of the People to Rule”, 1912. Library of Congress Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division.

Transcript: In order to succeed we need leaders of inspired idealism, leaders to whom are granted great visions, who dream greatly and strive to make their dreams come true; who can kindle the people with the fire from their own burning souls. The leader for the time being, whoever he may be, is but an instrument, to be used until broken and then to be cast aside; and if he is worth his salt he will care no more when he is broken than a soldier cares when he is sent where his life is forfeit in order that the victory may be won. In the long fight for righteousness the watchword for all of us is spend and be spent.

Stephen Somerstein, March on Selma, 1965. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society

In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson faced pressure from opposing camps. Civil rights advocates sought his support for voting-rights legislation after marchers for the cause were attacked in Selma, Alabama. But others, including Democrats from the president’s own party, were segregationists who pressed him to resist such change. The president was the leader of the nation and of the party, but on this issue he could not be both.

Johnson put his duty as leader of the nation first. Denying fellow Americans the right to vote, he said, was “wrong—deadly wrong.” He signed the 1965 Voting Rights Act at a high political cost, fully aware that the Democratic party would lose many Southern voters.

Watch a segment from LBJ's “Address to Congress about Voting Rights,” 1965.

Transcript: In our time we have come to live with the moments of great crisis. Our lives have been marked with debate about great issues; issues of war and peace, issues of prosperity and depression. But rarely in any time does an issue lay bare the secret heart of America itself. Rarely are we met with a challenge, not to our growth or abundance, or our welfare or our security, but rather to the values and the purposes and the meaning of our beloved Nation.

The issue of equal rights for American Negroes is such an issue. And should we defeat every enemy, and should we double our wealth and conquer the stars, and still be unequal to this issue, then we will have failed as a people and as a nation.

For with a country as with a person, “What is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?”

The Challenger crew (left to right): S. Christa McAuliffe, Gregory B. Jarvis, Judith A. Resnik, Francis R. “Dick” Scobee, Ronald E. McNair, Michael J. Smith, and Ellison S. Onizuka

Shortly before noon on January 28, 1986, the space shuttle Challenger broke apart in a fireball soon after it launched. All seven crewmembers died, and millions saw the tragedy unfold on TV. That night, President Ronald Reagan postponed his State of the Union in order to speak directly to the grief-stricken American people. He spoke movingly about the lives lost and offered a message of hope and determination.

Presidents must be ready in a moment’s notice to respond to the unexpected. They have the help of speechwriters, but it is the president’s task to appear in public, share in the trauma, and provide personal leadership. This duty is not mentioned in the Constitution, but many presidents have embraced it.

Watch a segment from Reagan’s “Speech on Space Shuttle Challenger,” 1986.

Transcript: We’ve grown used to wonders in this century. It’s hard to dazzle us. But for 25 years the United States space program has been doing just that. We’ve grown used to the idea of space, and, perhaps we forget that we’ve only just begun. We’re still pioneers. They, the members of the Challenger crew, were pioneers.

And I want to say something to the schoolchildren of America who were watching the live coverage of the shuttle’s take-off. I know it’s hard to understand, but sometimes painful things like this happen. It’s all part of the process of exploration and discovery. It’s all part of taking a chance and expanding man’s horizons. The future doesn’t belong to the fainthearted; it belongs to the brave. The Challenger crew was pulling us into the future, and we’ll continue to follow them.

The Presidents Timeline

- 1st | George Washington

1789–97

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 2nd | John Adams

1797–1801

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 3rd | Thomas Jefferson

1801–09

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- Louisiana Purchase

The United States purchases Louisiana Territory from France, 1803

Map showing Louisiana Territory, 1804. Boston Rare Maps

- 4th | James Madison

1809–17

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 5th | James Monroe

1817–25

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- Slavery

America’s prosperity relies on the forced labor of enslaved Africans, 1619–1865

Illustration of a slave ship, 1789

- 6th | John Quincy Adams

1825–29

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 7th | Andrew Jackson

1829–37

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 8th | Martin Van Buren

1837–41

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 9th | William Henry Harrison

1841

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 10th | John Tyler

1841–45

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 11th | James K. Polk

1845–49

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- U.S. Mexico War

The United States gains northern Mexico in the U.S. Mexico War, 1846–48

Battle of Buena Vista, 1851. University of Texas at Arlington Library

- 12th | Zachary Taylor

1849–50

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 13th | Millard Fillmore

1850–53

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 14th | Franklin Pierce

1853–57

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 15th | James Buchanan

1857–61

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 16th | Abraham Lincoln

1861–65

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- Civil War

The Civil War ends slavery, 1861–65

Union soldier with his family. Library of Congress

- 17th | Andrew Johnson

1865–69

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 18th | Ulysses S. Grant

1869–77

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- Transcontinental Railroad

The First Transcontinental Railroad spans the continent, 1869

“Across the Continent,” Frank Leslie’s, 1878. UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library

- 19th | Rutherford B. Hayes

1877–81

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 20th | James Garfield

1881

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 21st | Chester A. Arthur

1881–85

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 22nd and 24th | Grover Cleveland

1885–89 and 1893–97

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 23rd | Benjamin Harrison

1889–93

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 25th | William McKinley

1897–1901

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 26th | Theodore Roosevelt

1901–09

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- European Immigration

Immigration from Europe swells, 1903–14

U.S. Immigration Station, Ellis Island. Museum of the City of New York

- 27th | William Howard Taft

1909–13

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 28th | Woodrow Wilson

1913–21

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- World War I

The United States enters World War I, 1917–19

World War I posters. Library of Congress

- 29th | Warren G. Harding

1921–23

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 30th | Calvin Coolidge

1923–29

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 31st | Herbert Hoover

1929–33

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 32nd | Franklin D. Roosevelt

1933–45

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- World War II

The United States enters World War II, 1941–45

WWII poster. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society.

- 33rd | Harry S. Truman

1945–53

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- Civil Rights Movement

Civil rights activists agitate for an end to racial discrimination, 1940s–60s

March on Selma, 1963. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society.

- 34th | Dwight D. Eisenhower

1953–61

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 35th | John F. Kennedy

1961–63

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 36th | Lyndon B. Johnson

1963–69

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 37th | Richard M. Nixon

1969–74

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 38th | Gerald R. Ford

1974–77

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 39th Jimmy Carter

1977–81

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 40th | Ronald Reagan

1981–89

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 41st | George H.W. Bush

1989–93

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 42nd | Bill Clinton

1993–2001

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 43rd | George W. Bush

2001–2009

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 9/11

The largest foreign terror attack on US soil occurs on September 11, 2001

FDNY at Ground Zero, 2001. Library of Congress

- 44th | Barack Obama

2009–2017

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 45th | Donald J. Trump

2017–2021

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

- 46th | Joseph R. Biden

2021–

White House Collection/ White House Historical Association

Game

Playing the President: FDR’s First Hundred Days was created by the New-York Historical Society’s Teen Leader High School Interns. Teen Leaders worked with curators to conduct the core research and draft the script for the game’s content, and worked with a game design company to develop the concept and framework.

Teen programming takes place in the Tech Commons @ New-York Historical, a state-of-the-art digital media lab where teens create creative digital projects to share their historical scholarship.

Play GameResources

American Presidency Project: A non-profit repository of presidential documents, statistics, and media archive, hosted at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Annenberg Classroom Guide to the United States Constitution: Created by the Annenberg Public Policy Center, an interactive guide to the U.S. Constitution, with the original text and an explanation of the meaning of each article and amendment.

C-Span Series: American Presidents: Life Portraits: Companion site to C-SPAN’s Peabody Award-winning series profiling the presidents.

Government Agencies and Elected Officials: An official website of the United States government, detailing how the government is organized, and offering other government information and services.

iCivics: Online organization founded by former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, offering student and teacher resources for civics learning.

Library of Congress Manuscript Division Presidential Papers: The Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress holds the papers of twenty-three presidents. Many are digitized and searchable online.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Collection of Presidents, Vice Presidents, and First Ladies: A chronological list with entries for each president, along with first ladies and vice presidents.

Miller Center: University of Virginia research center, with facts, essays, transcripts and/or audio of select speeches, and other related content for all the U.S. Presidents.

Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery exhibit, America’s Presidents: National Portrait Gallery’s collection of presidential portraits, with history on the presidents and the paintings.

Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History exhibit, The American Presidency: A Glorious Burden: Exhibit on the Presidency by the National Museum of American History, including resources and teacher materials.

Supreme Court of the United States: Information on the structure and role of the present-day Supreme Court, current cases, oral arguments and rulings, as well as the history and traditions of the Court, and the Court building.

U. S. Capitol Visitor Center: Information, exhibitions, and educational resources about the history and functions of the houses of Congress and the Capitol building.

The White House: The official site for the White House and the President.

White House Historical Association: A non-profit organization with the mission to protect, preserve, and provide public access to the history of America’s Executive Mansion.

National Archives Presidential Library System

The Presidential Library system is composed of fourteen Presidential Libraries, one for each president since Herbert Hoover. These facilities are overseen by the Office of Presidential Libraries, in the National Archives and Records Administration. Each library contains documents, presidential artifacts, and educational and public programs.

Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, West Branch, IA

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, Hyde Park, NY

Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum, Independence, MO

Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum and Boyhood Home, Abilene, KS

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston, MA

Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum, Austin, TX

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, Yorba Linda, CA

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum, Ann Arbor, MI and Grand Rapids, MI

Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum, Atlanta, GA

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum, Simi Valley, CA

George H. W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum, College Station, TX

William J. Clinton Presidential Library and Museum, Little Rock, AR

George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum, Dallas, TX

Barack Obama Presidential Library, Hoffman Estates, IL

Presidential homes and historic sites are operated by private foundations and by the National Park Service. Many include tours, and offer exhibits, educational resources, and research opportunities.

White House Visitor Center, Washington, D.C.—administered by National Park Service

Federal Hall National Memorial, New York, NY, site of George Washington's inauguration and the First Congress—administered by National Park Service

George Washington, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, VA

George Washington Birthplace, Colonial Beach, VA—administered by National Park Service

John Adams and John Quincy Adams, Adams National Historical Park, Quincy, MA – administered by National Park Service

Thomas Jefferson, Monticello, Charlottesville, VA

James Madison, Montpelier, Montpelier Station, VA:

James Monroe, Highland, Charlottesville, VA:

Andrew Jackson, Hermitage, Nashville, TN

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, Kinderhook, NY—administered by National Park Service

William Henry Harrison, Grouseland, Vincennes, IN

John Tyler, Sherwood Forest, Charles City, VA

President James K. Polk Home and Museum, Columbia, TN

Millard Fillmore Presidential Site, East Aurora, NY

Franklin Pierce Historic Homestead, Hillsborough, NH

James Buchanan, Wheatland, Lancaster, PA

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site, Hodgenville, KY – administered by National Park Service

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, Lincoln City, IN—administered by National Park Service

Lincoln Home National Historic Site, Springfield, IL—administered by National Park Service

Lincoln, Ford’s Theater National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.—administered by National Park Service

Andrew Johnson National Historic Site, Greeneville, TN —administered by National Park Service

Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site, St. Louis, MO—administered by National Park Service

General Grant National Memorial, New York, NY—administered by National Park Service

Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museums at Spiegel Grove, Fremont, OH

James A. Garfield National Historic Site, Mentor, OH—administered by National Park Service

President Chester Arthur Historic Site, Fairfield, VT

Grover Cleveland Birthplace, Caldwell, NJ

Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site, Indianapolis, IN

William McKinley Presidential Library and Museum, Canton, OH

Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site, New York, NY – administered by National Park Service

Theodore Roosevelt National Park, Medora, ND – administered by National Park Service

Theodore Roosevelt, Sagamore Hill National Historic Site, Oyster Bay, NY – administered by National Park Service

Theodore Roosevelt Island National Memorial, McLean, VA – administered by National Park Service

William Howard Taft National Historic Site, Cincinnati, OH – administered by National Park Service

Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library and Museum, Staunton, VA

Woodrow Wilson Boyhood Home, Augusta, GA

President Woodrow Wilson House, Washington, DC

Warren G. Harding Home and Memorial, Marion, OH

Calvin Coolidge Presidential Library and Museum, Northampton, MA

Herbert Hoover National Historic Site, West Branch, IA – administered by National Park Service

Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site, Hyde Park, NY – administered by National Park Service

Harry S. Truman National Historic Site, Independence, MO – administered by National Park Service

Harry S. Truman Little White House, Key West, FL

Eisenhower National Historic Site, Gettysburg, PA – administered by National Park Service

John Fitzgerald Kennedy National Historic Site, Brookline, MA – administered by National Park Service

Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park, Johnson City, TX – administered by National Park Service

Jimmy Carter National Historic Site, Plains, GA – administered by National Park Service

Ronald Reagan Boyhood Home, Dixon, IL

President William Jefferson Clinton Birthplace Home, Hope, AR – administered by National Park Service

George W. Bush Childhood Home, Midland, TX

About the Exhibition

This online exhibition Meet the Presidents and its immersive tour of the Oval Office are digital versions of exhibitions that New-York Historical Society opened in the election year of 2020. Both offerings focus on the history of the U.S. presidency and answer the questions: What do presidents do? How have they interpreted and fulfilled the obligations of the office? How and why have their responsibilities evolved over time?

Meet the Presidents and the Oval Office are both on permanent display at New-York Historical. We welcome you to visit us and tour the exhibitions in person!

We deeply appreciate the work of all who took part in creating these exhibits, with special mention to historical consultants Dr. Meenekshi Bose, Dr. Sean Wilentz, Dr. David Kennedy, and Dr. Julian Zelizer; the firm of PBDW Architects; and the White House Historical Association, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum, and University of Virginia Miller Center.

Lead support for the installation of the Oval Office provided by Ira A. Lipman with generous support from Richard Gilder and Leonard & Judy Lauder. The Suzanne Peck and Brian Friedman Meet the Presidents Gallery is made possible by a generous gift from Suzanne Peck and Brian Friedman.

Construction of the Oval Office installation is supported, in part, by public funds from Manhattan Borough President Gale A. Brewer and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council as part of our Citizenship Project.

The work of the Presidential Historical Commission has been made possible by the generous support of Leonard A. Lauder and the late Ira A. Lipman.

Exhibitions at New-York Historical are made possible by Dr. Agnes Hsu-Tang and Oscar Tang, the Saunders Trust for American History, the Evelyn & Seymour Neuman Fund, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature. WNET is the media sponsor.