Women of Color in the

Struggle for Suffrage

Women of Color in the

Struggle for Suffrage

Unit Introduction

Women of color saw suffrage as essential to addressing problems faced by their communities.

The American women’s suffrage movement has been thought of as a campaign led and populated by white women, which overlooks the role played by Black, Latina, Asian, and Indigenous women.

Despite the barriers, women of color organized, marched, wrote, spoke out, and contributed to the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, though they were not all able to vote after 1920.

The vote is key to power in a democracy. Throughout American history, countless groups and individuals have fought to access this critically important right. The women’s suffrage movement is one of the most notable of these efforts. The dominant narrative of the women’s suffrage movement centers on the middle- and upper-class white women whose efforts are justly celebrated. But there is more to the story. Women of color actively took part in the campaign to win the vote for women. In general, the mainstream movement did not welcome their efforts, and as a result, their role and contributions have remained largely hidden.

Women and men supported the women’s suffrage movement for a range of reasons. For many white women, it was a question of fairness, equal rights, and the legal power to change laws and customs that kept women subservient to men. Suffragists of color shared these aims, but many also fought on behalf of their communities, who were often marginalized in ways that the right to vote could help remedy. Their struggle for the vote was merely one facet in a much larger fight to achieve racial equality and acceptance.

Both those who supported women’s right to vote and those who opposed it recognized the importance of the debate at hand. Women voters would alter the power dynamic and potentially upend the status quo. The enormous significance of the vote and deep disagreements about who should be able to access it is one reason why the suffrage movement struggled for decades to accomplish its goal.

This unit begins with The Road to Women’s Suffrage, an animated video that describes the arc of the mainstream suffrage movement from the 1848 Seneca Falls convention to the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. The remaining resources illustrate how women of color insisted on a place in the mainstream effort, dealt with racial bias and hostility, and mobilized their communities on behalf of women’s right to vote.

About Suffrage

Suffragist or suffragette? These terms have often been used interchangeably. But American women fighting for voting rights did not see them as identical. Suffragette was originally used to insult suffrage activists in Great Britain, since their behavior was seen as unladylike. British activists eventually chose to embrace the label. Their American counterparts were less confrontational and did not want to be associated with the more radical British movement. They called themselves suffragists, though their detractors often used suffragette as a pejorative.

For several decades in the 19th and early 20th centuries, writers and activists referred to “woman suffrage.” In this unit, "women's suffrage" is used except in historical references.

About Ethnicity and Terminology in this Unit

The United States government has no official definitions in regards to ethnicity or ethnic groups. It asks people to self-identify. The terms people use and feel comfortable with have varied over time and from region to region.

Whenever possible, this curriculum uses the most specific description available. Many, but not all, of those descriptions emphasize where an individual or their ancestors were born. Nina Otero-Warren is presented as a New Mexican and a woman of Mexican descent. Zitkala-Ša is described as a member of the Yankton Dakota Sioux Nation and Marie Bottineau Baldwin as belonging to the Turtle Mountain Ojibwe Nation.

In references to groups that cross boundaries of countries or tribal nations, the unit honors the preferences of communities today and of scholars. For example, people of Spanish or Latin American descent are referred to as Latina, Latino, or Latinx. Indigenous people are described as Indigenous or Native.

Historical materials are presented as they were written, and some of them use terms that are considered offensive or inappropriate today. In these instances, we have left the original document intact, but we request that you use contemporary and inclusive terminology when discussing the content with students.

When power is denied to people because of race, gender, or other aspects of identity, how do they seek to make change and gain influence?

Why is the vote so important to groups to whom it is denied?

Women of color were members of two marginalized groups. How did being both female and of color affect their thinking and their strategies in regard to suffrage?

How should we think about the suffrage movement, given the experiences of women of color before and after the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified?

The question of voting rights continues to divide Americans. Study a recent news story about efforts to limit voting rights. What arguments are used for and against? What links do you see to the arguments used about women’s suffrage in the 19th and early 20th centuries? Who do you think should have the right to vote?

This unit introduces several women of color who fought for suffrage. But there were many others who joined the effort. Some were relatively anonymous, and some were well known, such as Maria Guadalupe Evangelina de Lopez (Latina; see Reaching Spanish-Speaking Voters) and Carrie Williams Clifford (African American). Choose one of these women or another that you have found on your own to research further; then write a life story or make a class presentation that describes how she contributed to the drive for women’s suffrage.

Many men supported women’s rights, including W. E. B. Du Bois (an African American writer and activist), Rabbi Stephen Wise (a member of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage), and Senator Charles Curtis (a Kansas politician, member of the Kaw Nation, and vice president under Herbert Hoover). Choose one of these men to research further. Why did he support women’s rights? How did he show his support?

The Nineteenth Amendment became part of the US Constitution because members of Congress voted to pass it and then state legislators voted to ratify it. The vast majority were white men. (Congress had no Black members at the time but did include a small number of Indigenous and Latino men.) Hold a class discussion about why they might have supported voting rights for women. Review some of the materials in this unit. Which arguments do you think would have been most persuasive? How did suffragists tailor their arguments to appeal to men in power?

Research the Congressional Record for the debate and vote on the Nineteenth Amendment. For the House of Representatives, click here and go to p. 78. The roll call vote in the House appears on p. 93-4. For the Senate, click here. The debate about the amendment begins on p. 615, the final vote tally on p. 635.

Many women supported suffrage, but others did not. Read “Arguments for and Against Suffrage,” a resource in Women & the American Story. How did each side view the importance of the vote and its potential effect on women’s lives?

Click on the materials below to begin exploring this unit.

- Video: The Road to Women’s Suffrage

This video recounts the long campaign for women's suffrage in the United States.

Curriculum Connections: voting rights, women's rights, constitutional amendments

- Resource: A Woman of Color After the Civil War

This resource includes a video reenactment and text from a speech given by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper at the National Women's Rights Convention in 1866.

Curriculum Connections: voting rights, women's rights, Jim Crow

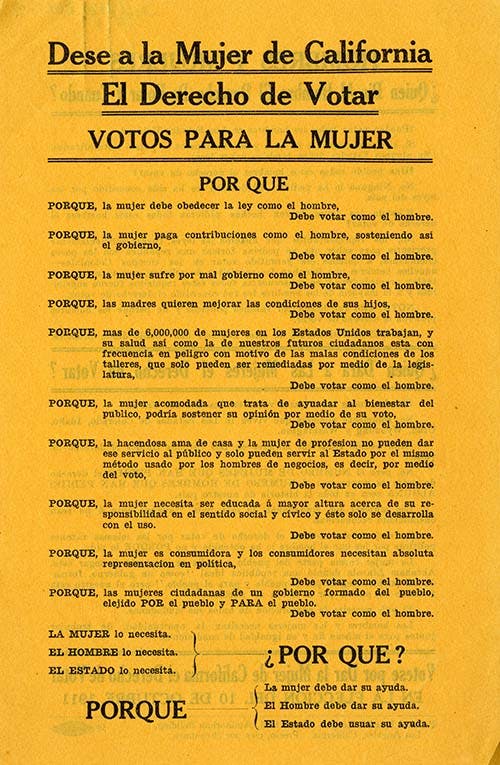

- Resource: Reaching Spanish-Speaking Voters

A suffrage poster from California translated into Spanish demonstrates efforts to reach Spanish-speaking voters.

Curriculum Connections: voting rights, voting referendums

- Resource: Race and the Suffrage Parade

A set of resources explores Black women's inclusion in the suffrage parade in Washington, DC, in 1913.

Curriculum Connections: voting rights, activism, organizing

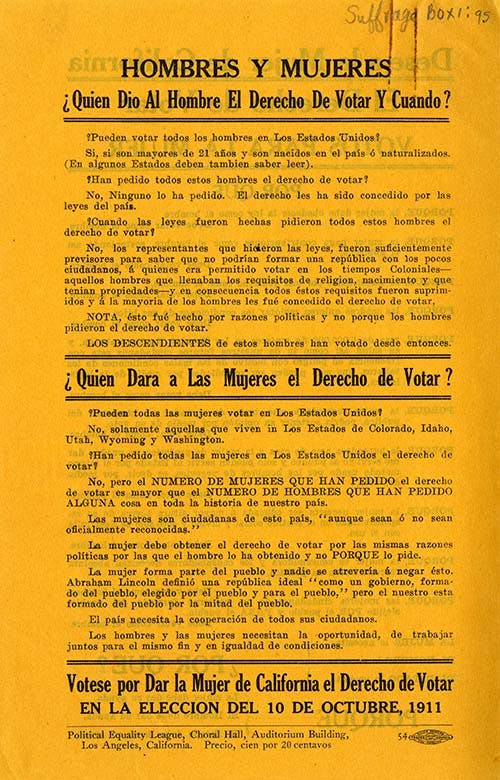

- Resource: Mabel Lee on Suffrage for Women

This document presents Mabel Lee's arguments about women's rights.

Curriculum connections: voting rights, women's rights, activism

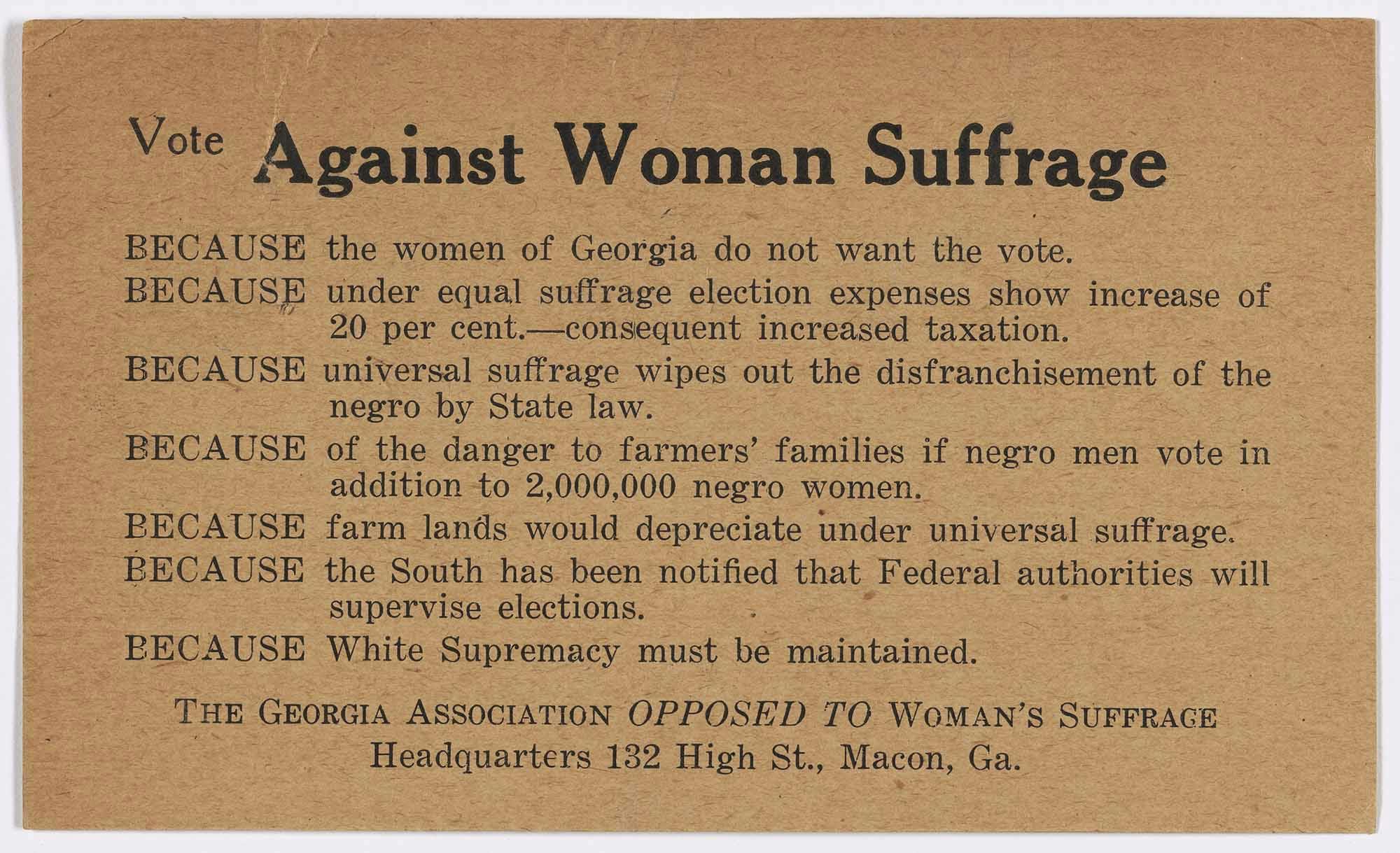

- Resource: Race and Suffrage in the South

A set of resources considers how women's suffrage efforts in Southern states were connected to the disenfranchisement of Black voters.

Curriculum connections: voting rights, Jim Crow

- Resource: Zitkala-Ša (Gertrude Bonnin) Argues for Indigenous Citizenship

This resource explores Zitkala-Ša's advocacy for Indigenous citizenship.

Curriculum connections: voting rights, women's suffrage, activism

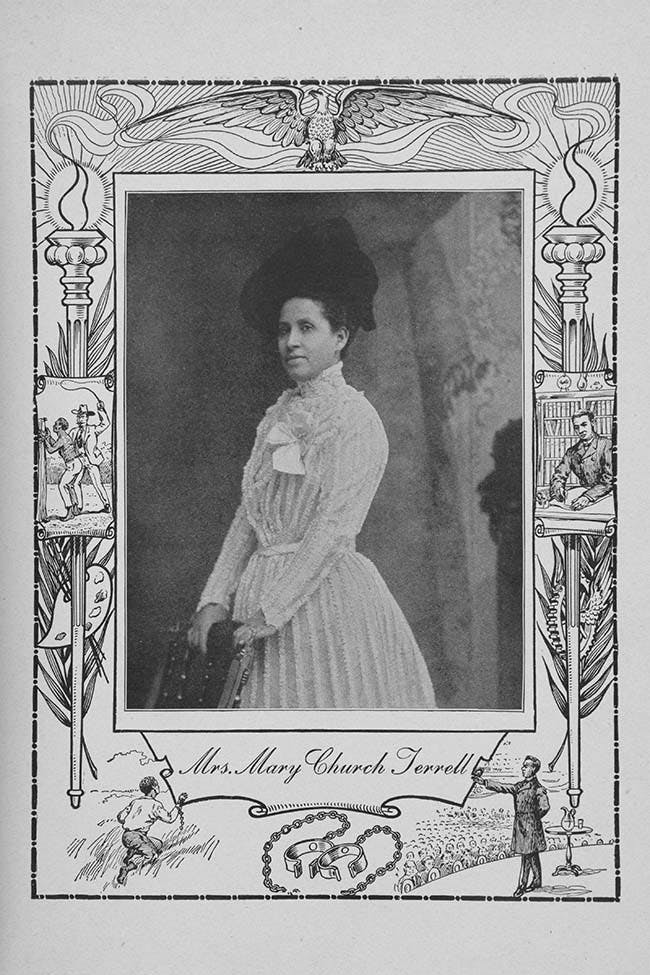

- Life Story: Mary Church Terrell

The story of a lifelong activist who advocated for suffrage and equal rights on local, national, and international stages.

Curriculum connections: voting rights, women's rights, activism

- Life Story: Mary Louise Bottineau Baldwin

One of the first two Native American women to obtain a law degree, Mary Louise Bottineau Baldwin worked for women's suffrage and Indigenous rights.

Curriculum connections: voting rights, women's suffrage, citizenship

- Life Story: Nina Otero-Warren

The story of a Latina woman who advocated for suffrage in New Mexico.

Curriculum connections: voting rights, women's suffrage, activism

Video: The Road to Women’s Suffrage

This video was created by the New-York Historical Society in collaboration with Makematic.

Journalists and authors Cokie Roberts and Elaine Weiss recount the long campaign for female suffrage. They describe both the deeply held beliefs about women’s alleged fragility and weakness and the coverture laws that kept women subservient to men through much of early American history. And they detail the critical steps taken from the mid-19th century to the dramatic vote in Tennessee that ratified the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920.

David M. Rubenstein is Co-Founder and Co-Chairman of The Carlyle Group, one of the world’s largest and most successful private investment firms. Established in 1987, Carlyle now manages $301 billion from 26 offices around the world.

Mr. Rubenstein is Chairman of the Boards of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the Council on Foreign Relations, the National Gallery of Art, and the Economic Club of Washington; a Fellow of the Harvard Corporation; a Trustee of the University of Chicago, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins Medicine, the Institute for Advanced Study, the National Constitution Center, the Brookings Institution, and the World Economic Forum; and a Director of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, among other board seats.

Mr. Rubenstein is a leader in the area of Patriotic Philanthropy, having made transformative gifts for the restoration or repair of the Washington Monument, Lincoln Memorial, Jefferson Memorial, Monticello, Montpelier, Mount Vernon, Arlington House, Iwo Jima Memorial, the Kennedy Center, the Smithsonian, the National Archives, the National Zoo, the Library of Congress, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Mr. Rubenstein has also provided to the U.S. government long-term loans of his rare copies of the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th Amendment, the first map of the U.S. (Abel Buell map), and the first book printed in the U.S. (Bay Psalm Book).

Mr. Rubenstein is an original signer of The Giving Pledge; the host of The David Rubenstein Show and Bloomberg Wealth with David Rubenstein; and the author of The American Story, How to Lead, and The American Experiment.

Cokie Roberts was a political commentator for ABC News and National Public Radio. She was the author of Founding Mothers, which focuses on the sisters, wives, mothers, and other women who influenced the nation’s founders. Capital Dames explores the women of Washington, DC, before and during the Civil War. Roberts died in 2019.

Journalist Elaine Weiss has written feature articles for many national publications. She is the author of Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War. Her study of the concerted effort to win Tennessee’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment is entitled The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote.

The women who fought for suffrage had no official political power. Nevertheless, they succeeded eventually, and the Nineteenth Amendment was added to the Constitution. List the strategies they used over the decades. How did they adjust to changing conditions?

Hold a class discussion about perseverance. What role did it play in the campaign for women’s right to vote? How do people stay committed to a cause for decades? What role does perseverance play in the lives of students or those around them?

Resource: A Woman of Color After the Civil War

We are all bound up together” – Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, filmed reenactment starring Ariana DeBose as Francis Harper, 2019. New-York Historical Society; Special thanks to the CUNY School of Professional Studies.

I feel I am something of a novice upon this platform. Born of a race whose inheritance has been outrage and wrong. Most of my life had been spent in battling against those wrongs. But I did not feel as keenly as others that I had these rights, in common with other women, which are now demanded.

I am new to the fight for suffrage. I have spent most of my life battling racial oppression. Until recently I did not feel that I had much in common with white women who are demanding equal rights.

About two years ago I stood within the shadows of my home. A great sorrow had fallen upon my life. My husband had died suddenly, leaving me a widow, with four children. I tried to keep my children together but my husband died in debt; and before he had been in his grave three months, the administrator had swept the very milk crocks and washtubs from my hands. I was a farmer’s wife and made butter for the market. But what could I do, when they had swept all away?

Two years ago my husband died suddenly. I was left alone with four children. I tried to take care of my children, but my husband left debts to be paid. The debt collector sold all my butter-making tools to pay them. What could I do for money when my work tools had been taken?

Had I died instead of my husband, how different would have been the result! By this time he would have had another wife, it is likely; and no administrator would have gone into his house, broken up his home, and sold his bed, and taken away his means of support.

If I had died instead of my husband, things would have been different. He would probably have remarried. No debt collector would have taken his things to repay his debts. [Harper is referring to the law of coverture, under which a husband legally owned his wife’s property. If a woman died, the assumption was that her husband would work to pay off debts, and the family’s belongings would not be seized.]

I say, then, that justice is not fulfilled so long as woman is unequal before the law. We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul. You tried that in the case of the negro. You pressed him down for two centuries; and in so doing you crippled the moral strength and paralyzed the spiritual energies of the white men of the country. When the hands of the Black were fettered, white men were deprived of the liberty of speech and the freedom of the press. Society cannot afford to neglect the enlightenment of any class of its members.

This country will never have justice as long as women are unequal. We are all one people, and society cannot oppress the weakest in society without damaging everyone. You tried to oppress Black people. You oppressed them for two hundred years. By doing so, you hurt the spiritual energy of white men in this country. When Black people were enslaved, white men were not allowed to thrive either and were deprived of their own rights. Society should not neglect anyone, because it is detrimental to all.

I do not believe that giving the woman the ballot is immediately going to cure all the ills of life. I do not believe that white women are dewdrops exhaled from the skies. I think, that like men, they can be divided into three classes: the good, the bad, and the indifferent. The good will vote according to their convictions and principles; the bad as dictated by prejudice or malice; and the indifferent will vote on the strongest side of the question, the winning party.

I do not think that giving women the ballot to vote is going to immediately fix all wrongs. I do not think white women can fix everything. I think, like men, white women can be divided into three groups: the good, the bad, and the uncaring. The good will vote in support of their own ideals, the bad will be controlled by prejudice and evil, and the uncaring will vote for whomever they think will win.

You white women speak here of rights and I speak of wrongs. I, as a colored woman, have had in this country an education which has made me feel as if I were in the situation of Ishmael, my hand against every man and every man’s hand against me. Let me go tomorrow morning and take my seat in one of your streetcars--I do not know that they will do it in New York, but they will in Philadelphia--and the conductor will put his hand and stop the car rather than let me ride.

White women speak of rights and I speak of wrongs. I, as a Black woman, have always felt alone. I must fight every person for equal rights, and every person will try to keep me down. If I tried to get on a streetcar tomorrow, the conductor would not let me on. Maybe they would in New York, but not in Philadelphia.

In advocating the cause of the colored man, since the Dred Scott decision, I have sometimes said I thought the nation had touched bottom. But let me tell you there is a depth of infamy lower than that. It is when the nation, standing upon the threshold of a great peril, reached out to its hands a feebler race, and asked that the race help it, and when the peril was over, said “You are good enough for soldiers but not good enough for citizens.”

I have been fighting for racial justice for nearly ten years, since the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision. I’ve sometimes thought this country had hit rock bottom. But I was wrong. We asked Black men to fight in the Civil War to save this nation. But after the war, we told them they were good enough to die for the country but not good enough to vote.

We have a woman in our country who has received the name of Moses, not by lying about it, but by acting it out. A woman who has gone down to the Egypt of slavery and brought out hundreds of our people into liberty. The last time I saw that woman, her hands were swollen. That woman, who was brave enough and secretive enough to act as a scout for the American Army, had her hands swollen from the conflict with a brutal conductor who undertook to eject her from her place. That woman, whose courage and bravery won a recognition from our army and from every Black man in this country, is excluded from every thoroughfare of travel. So talk of giving women the ballot box. Go on! It is a normal school and the white women of this country need it. While there exists this brutal element in society which tramples upon the feeble and treads down the weak, I tell you that if there is any class of people who need to be lifted out of their airy nothings and selfishness, it is the white women of America.

There is a Black woman people call Moses [Harriet Tubman]. She earned that nickname by helping hundreds of Black people self-emancipate. When I saw her last, her hands were injured. That woman, who was a scout for the Union Army, had been injured fighting with a streetcar conductor who threw her off a street car. That woman, who was recognized by the US Army and who is a hero to all Black men in this country, is not allowed to use public transit. So, sure, you can talk about giving women the right to vote. White women need it. But while this kind of racism still continues, it is white women who need to be reeducated about the real oppression happening in America.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, “We Are All Bound Up Together,” 1866. Transcription, New-York Historical Society.

I feel I am something of a novice upon this platform. Born of a race whose inheritance has been outrage and wrong. Most of my life had been spent in battling against those wrongs. But I did not feel as keenly as others that I had these rights, in common with other women, which are now demanded.

About two years ago I stood within the shadows of my home. A great sorrow had fallen upon my life. My husband had died suddenly, leaving me a widow, with four children. I tried to keep my children together but my husband died in debt; and before he had been in his grave three months, the administrator had swept the very milk crocks and washtubs from my hands. I was a farmer’s wife and made butter for the market. But what could I do, when they had swept all away?

Had I died instead of my husband, how different would have been the result! By this time he would have had another wife, it is likely; and no administrator would have gone into his house, broken up his home, and sold his bed, and taken away his means of support.

I say, then, that justice is not fulfilled so long as woman is unequal before the law. We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul. You tried that in the case of the negro. You pressed him down for two centuries; and in so doing you crippled the moral strength and paralyzed the spiritual energies of the white men of the country. When the hands of the Black were fettered, white men were deprived of the liberty of speech and the freedom of the press. Society cannot afford to neglect the enlightenment of any class of its members.

I do not believe that giving the woman the ballot is immediately going to cure all the ills of life. I do not believe that white women are dewdrops exhaled from the skies. I think, that like men, they can be divided into three classes: the good, the bad, and the indifferent. The good will vote according to their convictions and principles; the bad as dictated by prejudice or malice; and the indifferent will vote on the strongest side of the question, the winning party.

You white women speak here of rights and I speak of wrongs. I, as a colored woman, have had in this country an education which has made me feel as if I were in the situation of Ishmael, my hand against every man and every man’s hand against me. Let me go tomorrow morning and take my seat in one of your streetcars--I do not know that they will do it in New York, but they will in Philadelphia--and the conductor will put his hand and stop the car rather than let me ride.

In advocating the cause of the colored man, since the Dred Scott decision, I have sometimes said I thought the nation had touched bottom. But let me tell you there is a depth of infamy lower than that. It is when the nation, standing upon the threshold of a great peril, reached out to its hands a feebler race, and asked that the race help it, and when the peril was over, said “You are good enough for soldiers but not good enough for citizens.”

We have a woman in our country who has received the name of Moses, not by lying about it, but by acting it out. A woman who has gone down to the Egypt of slavery and brought out hundreds of our people into liberty. The last time I saw that woman, her hands were swollen. That woman, who was brave enough and secretive enough to act as a scout for the American Army, had her hands swollen from the conflict with a brutal conductor who undertook to eject her from her place. That woman, whose courage and bravery won a recognition from our army and from every Black man in this country, is excluded from every thoroughfare of travel. So talk of giving women the ballot box. Go on! It is a normal school and the white women of this country need it. While there exists this brutal element in society which tramples upon the feeble and treads down the weak, I tell you that if there is any class of people who need to be lifted out of their airy nothings and selfishness, it is the white women of America.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, “We Are All Bound Up Together,” 1866. Transcription, New-York Historical Society.

After the Civil War, activists for women’s suffrage competed with activists for Black rights. Both tried to advance their causes. Some white women suffragists believed they deserved the right to vote because they had worked hard to support the war. Those who held to white supremacy resented the idea that Black men would have power over them at the ballot box. Some believed that white women’s rights should come before those of Black Americans. Many Black activists wanted to see the rights of Black men guaranteed immediately, but they were often uncertain that granting women the right to vote was a good idea.

Black women suffragists represented the intersection of these two positions by demanding the right to vote for all men and women regardless of race. They also spoke out about issues specific to Black communities. They called for increased legal protections, more employment opportunities, and financial independence for all Black Americans.

This video is a reenactment of a speech given by Black activist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, one of the founders of the National Association of Colored Women. Harper was invited to speak at the 11th National Woman’s Rights Convention in New York City in 1866. At the time, the US government was debating whether to grant full citizenship to the millions of Black people freed from slavery by the Thirteenth Amendment. At the same time, white women suffragists were leading a major campaign to secure women’s right to vote.

Harper told her mostly white audience that if Black and white activists worked together to win voting rights for all Americans, everyone would benefit. She also asked white activists to acknowledge and fight against the extreme inequalities Black people faced in the United States. The audience was so inspired by her words that they voted to form the American Equal Rights Association, a group that promoted voting rights for women and Black people.

- suffrage

The right to vote.

- suffragist

An activist working to win women’s right to vote.

- Thirteenth Amendment

The constitutional amendment that outlawed slavery in the United States.

How did Frances Ellen Watkins Harper tie women’s rights and Black rights together in her speech?

How did Harper differentiate herself from white women suffragists? Why did she feel this distinction was necessary?

How did Harper’s experience as a widow shape her thinking about women’s rights?

Why would Harper make this speech in 1866? What else was happening in America?

All human beings have power, even if they are denied legal rights. Analyze the arguments Harper used in her address to a mostly white audience. How did she demonstrate and use her personal power in this speech? Think about what she said, how she phrased it, and who her audience was.

Research the life of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. What were her early experiences? As an activist, what did she care about? After her “All Bound Up” speech, how did she continue to fight for women’s rights?

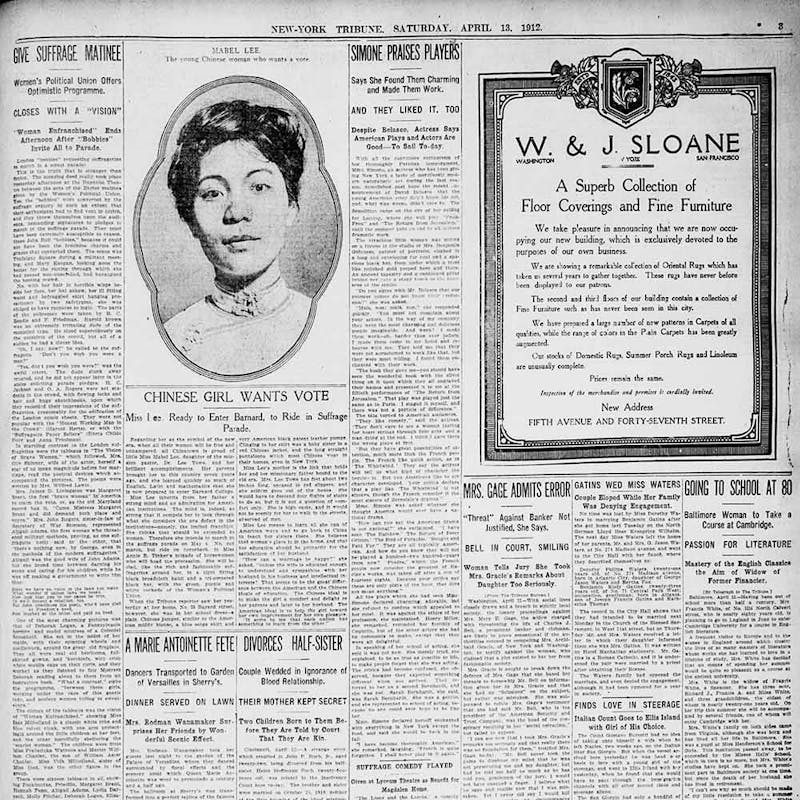

Resource: Reaching Spanish-Speaking Voters

To access an English translation of this document as a PDF, click below.

English TranslationIn 1874, the Supreme Court ruled, in Minor v. Happersett, that women were citizens but they could not vote. Suffragists adjusted their strategies. If they could not gain voting rights at the national level, they would work state by state. In 1896 they tried in California but failed, mostly because people in cities voted against it. In 1911 they again convinced state legislators to add a suffrage referendum to the state ballot. The state’s voters, all of them male, would decide if California women had the right to vote.

The months leading to election day were intense. Many Californians opposed the referendum. They argued that women had no place in politics and should focus on raising their children. But suffrage organizations, including Votes for Women and the Political Equality League, mounted a massive campaign. Assuming they would again lose in the cities, they focused especially on rural areas. Activists from other states came to join the effort. The referendum’s supporters wrote editorials and spoke at meetings in church halls, union events, anywhere they could. They flooded the state with campaign buttons, posters, banners, and over three million pieces of literature.

More than 146,000 Californians voted on the referendum. The yes votes outnumbered the no votes by only 3,500. The slim victory was thanks to voters in rural and farm areas. Because of these results, an amendment was added to the state constitution, giving California women the right to vote in state and federal elections. The victory thrilled and energized suffragists across the country. It demonstrated how organization, effort, and an army of supporters could lead to a win.

Click here for more information, including the text of the California constitutional amendment.

The suffragists’ goal was to convince every California voter to back the referendum. Among other actions, they printed and distributed documents that could be handed out to individuals, posted in shop windows, or discussed in meeting rooms. This flyer presents many of the arguments they used. It was first written in English for English-speaking residents of the state. It was likely translated into Spanish by Maria Guadalupe Evangelina de Lopez. (The flyer slightly misquotes Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which ends, “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”)

In 1911, California’s Spanish-speaking population was relatively small, about 5% of the state total. But every vote counted. Maria de Lopez traveled the state to urge men with Mexican and Spanish backgrounds to vote in favor of the referendum. She once addressed a rally in Los Angeles entirely in Spanish, which no one had done before. A teacher of English as a second language, she translated many suffrage documents into Spanish and was a major force in the 1911 campaign.

This flyer presented dozens of reasons why California women should be allowed to vote. It was printed on gold paper, as were many of the documents from the California campaign. Gold was the campaign’s color theme.

- Colorado, Idaho, Utah, Wyoming, and Washington

Women had already won the right to vote in these states by 1911, beginning with Wyoming in 1890.

- naturalized citizen

A person born outside the United States who meets the requirements and becomes a US citizen after immigrating.

- representatives who made the laws

A reference to the founders who wrote the US Constitution.

The suffrage movement wanted to convince voters--all of whom were men--to grant the vote to women. What arguments does this document use? Which sound most persuasive to you?

Planners wanted the campaign to be positive, hopeful, constructive. Why do you think they adopted that tone? In this flyer, how well did they succeed?

In small print, the Political Equity League offered 100 copies of the flyer for $.20, about the price for two quarts of milk in 1911. What does this suggest about how the flyers were used? Why do you think they weren’t free?

How did Maria de Lopez contribute to the success of the 1911 California referendum? Why were her efforts important to her and to Latinas and Latinos?

A California senator, J. B. Sanford, was one of the major opponents of this referendum. Read his argument here. What are his main reasons for resisting women's suffrage? What audience do you think he was addressing? Compare Sanford’s position to the one presented in the flyer. How did pro suffrage forces address Sanford’s argument?

Research the life of Maria Guadalupe Evangelina de Lopez. How did she use her education and skills on behalf of Spanish-speaking Californians?

Resource: Race and the Suffrage Parade

As far as I am aware, I am actuated by no race prejudice in this matter. . . .

It seems to me it would be unfortunate if we had any large number of negroes in our Suffrage Procession. The prejudice against them is so strong in this section of the country that I believe a large part if not a majority of our white marchers will refuse to participate if negroes in any number formed a part of the parade. . . . The feeling against them here is so bitter that as far as I can see we must have a white procession, or a negro procession, or no procession at all. . . . I think that this suffrage procession will help the suffrage cause and therefore I wish to see it go through. . . . The best thing is to say nothing whatever about the question, to keep it out of the newspapers, to try to make this a purely Suffrage demonstration entirely uncomplicated by any other problems such as racial ones.

“Alice Paul (1885-1977) to Alice Stone Blackwell (1857-1950),” January 15, 1913. NWP Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (056.00.00).

Fearing that a letter which I sent you has gone astray, I am sending you the same matter. There are a number of college women of Howard University who would like to participate in the woman suffrage procession on Monday, March the third. We do not wish to enter if we must meet with discrimination on account of race affiliation. Can you assign us to a desirable place in the college women’s section?

"Nellie M. Quander (1880–1961) to Alice Paul (1885–1977)," February 17, 1913. NWP Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (060.00.00).

Suffrage parades were meant to attract the public’s attention and to show the large numbers of women who were committed to winning the right to vote. The 1913 parade in Washington, DC, was one of the largest. It was also the first to take place in the nation’s capital, or to demand a constitutional amendment permitting women to vote.

The parade was organized by the National American Woman Suffrage Association. One of its leaders, Alice Paul, had just two months to plan and oversee every detail. The date would be March 3, 1913, the day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson as president. The parade route would follow Pennsylvania Avenue, linking the demand for suffrage to the federal government and the capital city’s most famous street. Participants would wear signature colors and some wore matching outfits. They would march with their state delegations or in groups according to their profession, school, or other association.

Women of color were eager to take part. Indigenous women, and at least one Chinese woman, were assigned places in the various sections. But Alice Paul hoped to prevent Black women from marching. Rumors circulated that they would be relegated to the back of the parade. Confusion about the parade rules kept some Black women from joining the procession.

In the end, more than 5,000 marchers took part, many women of color were among them. And Black women did not walk as a group at the back of the parade. Instead, they joined their state, school, or professional sections, as white marchers did.

Alice Paul wrote this letter to Alice Stone Blackwell very early in the parade’s planning process. She had heard that one of the parade volunteers planned to contact Blackwell to inquire about Black women marching. Paul gave Blackwell her thoughts on the question. Blackwell responded in agreement. Both Paul and Blackwell said they did not personally object to Black marchers. As the parade’s organizers, however, they feared large numbers of Black marchers would offend many white marchers. And the loss of white support could seriously damage the suffrage campaign.

Nellie Quander wrote to Alice Paul twice on behalf of her sorority at Howard University, Alpha Kappa Alpha. Paul responded, but not until the end of February, just days before the march. She asked that Quander come to her office to discuss the group’s location in the parade. There is no evidence that Quander and Paul met or that Alpha Kappa Alpha women marched in the parade as a group.

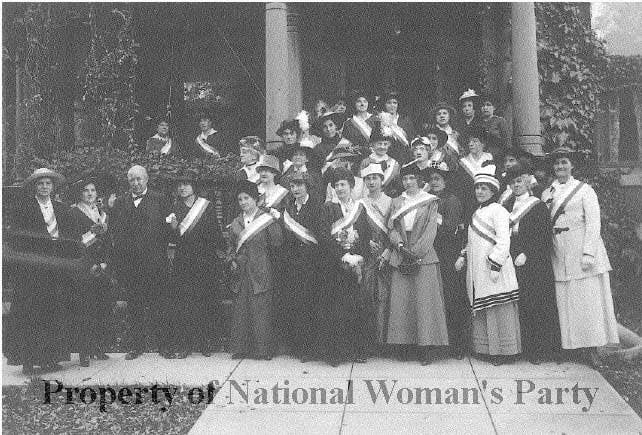

In 1913 Delta Sigma Theta was a new sorority at Howard University. The group’s mentor was Mary Church Terrell, and its mission was political action. Members of this sorority, along with Terrell, marched in the parade’s college section. It was their first public act as an organization.

Noted writer and antilynching crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett was an official member of the Illinois delegation to the parade. When the group arrived in Washington, parade organizers asked that the delegation be “entirely white.” Wells-Barnett refused to be excluded, and others in the Illinois delegation supported her. Responding to rumors, two Illinois delegates, Belle Squier and Virginia Brooks, said that if Wells-Barnett were forced to walk at the back of the parade, they would walk with her. On parade day Wells-Barnett waited in the crowd until the Illinois delegation approached and then joined it. Squier and Brooks made a point of marching alongside her. The photo captures the three of them, Squire and Brooks on the left and Wells-Barnett in the center. It was one of three parade photos taken for and printed in the Chicago Daily Tribune. This copy was taken from the microfilm archive of the Tribune. The original has apparently been lost.

- actuated

Motivated.

- affiliation

Membership.

- this section of the country

A reference to Washington, DC, and its Southern culture and attitudes.

Why did Alice Paul hope to keep discussions about Black marchers out of the newspapers?

The suffrage movement is typically portrayed as the accomplishment of white women. Why do you think the roles played by women of color have continued to be overlooked?

Why was the participation of Black sorority members important? What is the role of young, educated people in campaigns for civil rights? What political causes attract people your age today?

Why do you think parade organizers chose the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration to hold the parade? What did the date and the parade route say about the fight for suffrage and the connection between the vote and other forms of political power?

Study Alice Paul’s letter along with Race and Suffrage in the South. Consider her strategy for minimizing or eliminating the presence of Black women in the parade. How do you evaluate her decision to put white women’s suffrage above the rights of Black women?

Research the life of Nellie Quander. What social and political issues concerned her during the course of her life?

Resource: Mabel Lee on Suffrage for Women

It is a fact that no matter where we go we cannot escape hearing about woman suffrage. Yet there is hardly a question more misunderstood or that has more misapplications. So manifold are its misconceptions that it has come to be a by-word suitable for every occasion. For instance, if when in company one should wish to scramble out of an embarrassing situation, or his more fortunate brother should wish to be considered witty, all that either would have to do would be to mention woman suffrage, and they may be sure of laughter and merriment in response.

Everyone these days is talking about women voting. But many are laughing at it, as if it’s a joke.

The reason for this is that the idea of woman suffrage at first stood for something abnormal, strange and extraordinary, and so has finally become the word for anything ridiculous. The idea that women should ever wish to have or be anything more than their primitive mothers appears at first thought to be indeed tragic enough to be comic; but if we sit down and really think it over, throwing aside all sentimentalism, we find that it is nothing more than a wider application of our ideas of justice and equality. We all believe in the idea of democracy; woman suffrage . . . is the application of democracy to women. . . .

Why are people laughing? Because the idea seems so weird to them. They don’t understand that women could want more opportunities than their mothers had. But the vote is just democracy being applied to women.

The opponents of democracy [are] . . . saying that the feminists wish to make women like men; whereas the feminists want nothing more than the equality of opportunity for women to prove their merits and what they are best suited to do. . . . It was not so long ago that even Western people thought that woman was not capable of being taught even the three R’s. . . . It is only a short time since she gained the victory of admission to college, and there are still many schools too conservative to open their doors for her instruction. At present there is still the cry that though woman has gone so far, she can go no further, that she cannot succeed in the professions. But this again is being refuted by the success of pioneers of today.

People opposed to women’s rights say feminists want women to be like men. But women just want equal opportunities. They want an education. They want to go as far as they can in life. Some people say women have reached their limit, but they are wrong.

Mabel Lee, “The Meaning of Woman Suffrage,” The Chinese Student Monthly (May 1914), 526-529.

It is a fact that no matter where we go we cannot escape hearing about woman suffrage. Yet there is hardly a question more misunderstood or that has more misapplications. So manifold are its misconceptions that it has come to be a by-word suitable for every occasion. For instance, if when in company one should wish to scramble out of an embarrassing situation, or his more fortunate brother should wish to be considered witty, all that either would have to do would be to mention woman suffrage, and they may be sure of laughter and merriment in response.

The reason for this is that the idea of woman suffrage at first stood for something abnormal, strange and extraordinary, and so has finally become the word for anything ridiculous. The idea that women should ever wish to have or be anything more than their primitive mothers appears at first thought to be indeed tragic enough to be comic; but if we sit down and really think it over, throwing aside all sentimentalism, we find that it is nothing more than a wider application of our ideas of justice and equality. We all believe in the idea of democracy; woman suffrage . . . is the application of democracy to women. . . .

The opponents of democracy [are] . . . saying that the feminists wish to make women like men; whereas the feminists want nothing more than the equality of opportunity for women to prove their merits and what they are best suited to do. . . . It was not so long ago that even Western people thought that woman was not capable of being taught even the three R’s. . . . It is only a short time since she gained the victory of admission to college, and there are still many schools too conservative to open their doors for her instruction. At present there is still the cry that though woman has gone so far, she can go no further, that she cannot succeed in the professions. But this again is being refuted by the success of pioneers of today.

Mabel Lee, “The Meaning of Woman Suffrage,” The Chinese Student Monthly (May 1914), 526-529.

Chinese men began arriving in large numbers in the western United States in the mid-1850s, looking for work. Many white working-class men resented them, believing Chinese workers stole jobs from white workers who were more deserving. The Chinese were seen as more foreign than immigrants from Europe, too unlike white Americans to ever fit in. Resentment against them grew and spread across the country. In 1882 the Chinese Exclusion Act barred Chinese laborers from entering the United States and denied US citizenship to those already in the country. Because they were not citizens, Chinese Americans were unable to vote. (See the New-York Historical Society curriculum, Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion for more on this topic.)

Mabel Lee and her parents were born in China, where she was named Lee Ping-Hua. Her father was a missionary, not a laborer, so he was allowed to immigrate to the US during the period of Chinese exclusion. (Government officials, students, teachers, merchants, and tourists were also permitted to enter.) The Lee family settled in New York City in 1905, when Mabel was nine.

In 1911, when anti-Chinese feeling was widespread in America, a revolution began in China. Its leader promised to overthrow the emperor, establish a republic, and allow women to vote. White suffragists in the US believed a rumor that Chinese women could already vote. (In fact, China did not fully enfranchise women until decades later.) They publicized this news and shamed American men for being behind China, which many white Americans considered backward. And to highlight China’s progress, they invited Mabel Lee to take a prominent position in the 1912 suffrage parade in New York City, where she was about to enter Barnard College.

Mabel Lee expected to return to China one day, but she spent her life in the United States. She earned a PhD in Economics from Columbia University in 1921, the first Chinese woman to do so.

The photograph of Mabel Lee appeared in the New-York Tribune on a Saturday, exactly three weeks before the planned suffrage parade in New York City. The accompanying article quoted her views on the common concern that educated women would not be good wives: “How can a marriage be happy unless the wife is educated enough to understand and sympathize with her husband in his business and intellectual interests? That seems to be the great difference between the American and the Chinese ideals of education. The Chinese ideal is to make the girl a comfort and delight to her parents and later to her husband. The American ideal is to help the girl toward her own improvement for her own pleasure. It seems to me that each nation has something to learn from the other.”

Two years later, Lee wrote “The Meaning of Woman Suffrage.” It was published in the Chinese Student Monthly, her first article for this national journal. It was written for, and read by, Chinese students across America, most of whom were male. Lee’s article was focused on women’s rights in China. But her argument captures how she felt about women’s rights more broadly.

- by-word

A common saying.

- feminists

People who believe women should have rights equal to men.

- manifold

Obvious.

- merriment

Fun.

- merits

Worth.

- misapplications

Cases in which something, such as a word or an idea, is used in the wrong way.

- misconceptions

Inaccurate beliefs.

- primitive

Old-fashioned, not modern.

- professions

Careers requiring high levels of education, like lawyer and doctor.

- sentimentalism

The state of being too emotional, especially valuing feelings more than thinking.

- Three R’s

Reading, writing, and arithmetic. The first consonant sound in each word is the letter R.

Why did parade organizers give Mabel Lee such a prominent position in the march? What points were they making?

The New-York Tribune for April 13, 1912, was 14 pages long. It included only one photograph: Mabel Lee’s. Why do you think the Tribune printed this photo?

In her article, Mabel Lee noted that women’s suffrage was often treated as a joke. What was her response?

Why do you think people laughed at the idea of women voting? Do similar things happen today? Have you heard people laugh at traits or identities you didn’t find funny?

Read the New-York Tribune article that accompanied this photo here. How did the reporter indicate a positive opinion of Mabel Lee? What details and language did he or she use? How did the photo contribute to the tone of the article?

Chinese laborers searched for ways to evade the Chinese Exclusion Law and enter the United States. Sometimes they pretended to be what they were not. Read “The Case of the Alleged Merchant” in Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion. Compare this man’s story to Mabel Lee’s. Why were their experiences so different? How did different Americans see race, gender, and class during the last years of the suffrage movement?

Resource: Race and Suffrage in the South

For decades, American suffragists pursued two parallel strategies. One was to seek an amendment to the Constitution. Starting in 1868, supporters introduced the women’s suffrage amendment in every session of Congress. The other strategy was to win voting rights in individual states.

Over time, many suffrage leaders lost faith in the state-by-state strategy. It was too expensive and time-consuming and too scattered. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was the largest organization working for women’s right to vote. When it organized a parade in Washington, DC, in 1913, NAWSA was actively promoting a constitutional amendment. In one stroke it would extend voting rights to every woman in the country. The model was the Fifteenth Amendment, which enfranchised Black men after the Civil War.

But the constitutional amendment issue divided the suffrage movement. Alice Paul, who had organized the 1913 parade, broke with NAWSA, which she considered too moderate. She started the Congressional Union, later called the National Women’s Party. Paul’s group worked aggressively for a constitutional amendment, while NAWSA focused both on the amendment and on suffrage laws in individual states.

The emphasis on a constitutional amendment alarmed many Southerners. They thought it would bring federal interference in states’ constitutional right to determine voter qualifications within their borders. States had used this power to establish literacy tests and other measures that prevented nearly all Black men in the South from voting, despite the Fifteenth Amendment.

Women’s suffrage became a new front in the old war over Black voting rights in the South. In some Southern states and in many voting districts, the Black population outnumbered the white.

Many Southerners believed that if Black men and women could vote, white power in the South would be lost. So some Southerners wanted to grant suffrage to white women only. Others hoped to keep all women from voting. Both camps were motivated by a fear of Black people voting in great numbers, with the federal government’s support.

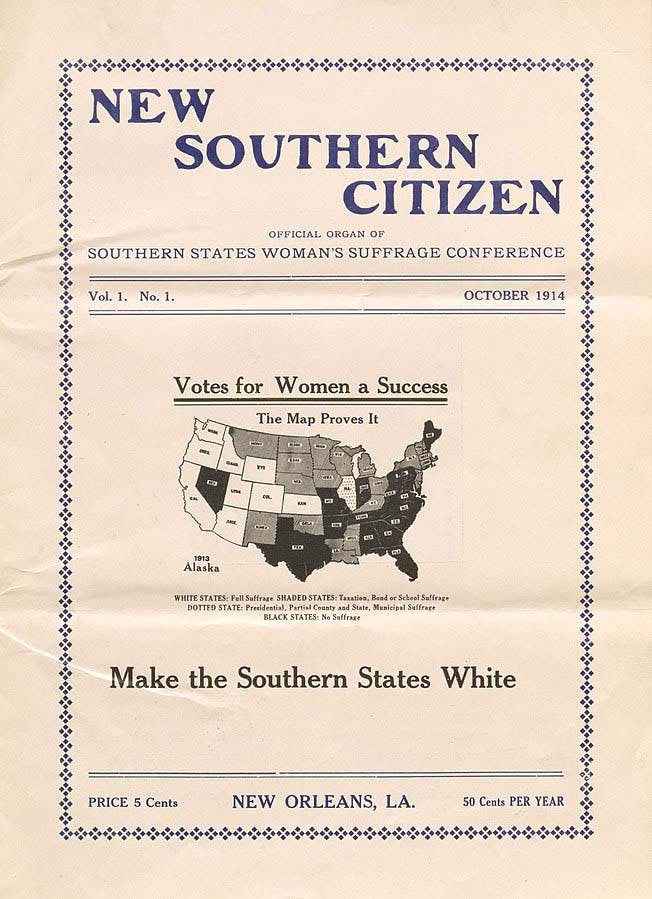

New Southern Citizen was the official publication of the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference. Kate Gordon founded the Conference in New Orleans in 1913. She was the group’s president and the editor of the Citizen. A longtime suffragist, she had been the recording secretary of NAWSA. But she broke with the national group because it supported a suffrage amendment to the Constitution. Gordon worked for state suffrage laws because she wanted voting rights for white women only. She believed that Jim Crow laws, like literacy tests, which prevented Black men from voting, would also work against Black women. But she worried that these laws violated the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and could eventually be overturned by the federal government. If federal authorities became involved, the South might be forced to allow Black people to vote. So she worked hard to maintain states’ control over voting, and she placed a map of the states on the cover of the Citizen’s first issue. Those that had passed women’s suffrage laws were presented with no shading or color, so they appeared as white. States that had no women’s suffrage laws at all, including most of the South, were shown in black. In this way she used black and white in the printed document to allude to racial attitudes and fears.

The National Association Opposed to Women Suffrage (NAOWS) was organized in New York City in 1911. It drew men and women who were against women voting. Some of them believed women were not as smart as men. Some believed women were better off without the vote. The Georgia chapter of NAOWS formed in 1914 and soon claimed that its membership outnumbered the state’s suffragists. The postcard presented its arguments against women’s suffrage. It was mailed to members of the 64th Congress, which met from March 4, 1915, to March 4, 1917. Included with the mailing was a letter that stated, “We are sure our southern men grant us all privileges and rights we should have and do not want to add a million negro women to the electorate."

- depreciate

Lose value.

- disfranchisement

Denial of voting rights.

- full suffrage

Women in the “white states” were able to vote in state, local, and federal elections.

- Jim Crow

The name for the many laws, rules, and customs that maintained segregation after the Civil War, often through violence and intimidation. The original Jim Crow was a minstrel character created to ridicule Black Americans.

- Presidential, Partial County and State, Municipal Suffrage

In Illinois, women were able to vote in presidential and in some state and local elections.

- Taxation, Bond or School Suffrage

In several states, especially in the North, women were able to vote on their state’s financial decisions and in school elections, but not otherwise.

Based on these resources, what did Southern pro- and antisuffrage groups have in common? How did they differ?

The New Southern Citizen cover featured the tagline “Make Southern States White.” What did it mean?

Why would the Georgia antisuffrage group send their materials to members of Congress? Why did they make the particular arguments they included on the postcard, and why in that order?

Research the ratification votes for the Nineteenth Amendment. How many of the states shown as black on the New Southern Citizen map were among the 36 required to ratify the amendment? When did Georgia ratify?

Read Resources 8 and 13 in the Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow curriculum. How did the culture of Jim Crow contribute to Southern attitudes about women’s suffrage?

Resource: Zitkala-Ša (Gertrude Bonnin) Argues for Indigenous Citizenship

The eyes of the world are upon the Peace Conference sitting at Paris. Under the sun a new epoch is being staged! Little peoples are to be granted the right of self determination! . . . The world is to be made better. . . .

Leaders in Paris are making decisions that will improve the whole world. Little people—small countries and groups that lack power—will have more freedom and more control over their lives.

Paris, for the moment, has become the center of the world’s thought. Divers human petitions daily ascend to its Peace Table. . . . Many classes of men and women [are] clamoring for a hearing. . . . Women of the world, mothers of the human race, are pressing forward for recognition. . . . The Black man of America is offering his urgent petition. . . . Their fathers, sons, brothers and husbands fought and died for democracy. Each is eager to receive the reward for which supreme sacrifice was made. . . .

Many people, including women all over the world and Black Americans, are appealing to the leaders in Paris. They too had relatives who died fighting the war, and they want a share of this new and better world.

The Red man asks for a very simple thing, -- citizenship in the land that was once his own, --America. Who shall represent his cause at the World’s Peace Conference? The American Indian, too, made the supreme sacrifice for liberty’s sake. He loves democratic ideals. What shall world democracy mean to his race?

Native Americans fought and died for democracy too. Now they ask to be granted citizenship and the right to vote. This is the time to do it!

There never was a time more opportune than now for America to enfranchise the Red man!

Gertrude Bonnin, "Editorial Comment", The American Indian Magazine, Vol. VI, Winter, 1919, No. 4, 161-162.

The eyes of the world are upon the Peace Conference sitting at Paris. Under the sun a new epoch is being staged! Little peoples are to be granted the right of self determination! . . . The world is to be made better. . . .

Paris, for the moment, has become the center of the world’s thought. Divers human petitions daily ascend to its Peace Table. . . . Many classes of men and women [are] clamoring for a hearing. . . . Women of the world, mothers of the human race, are pressing forward for recognition. . . . The Black man of America is offering his urgent petition. . . . Their fathers, sons, brothers and husbands fought and died for democracy. Each is eager to receive the reward for which supreme sacrifice was made. . . .

The Red man asks for a very simple thing, -- citizenship in the land that was once his own, --America. Who shall represent his cause at the World’s Peace Conference? The American Indian, too, made the supreme sacrifice for liberty’s sake. He loves democratic ideals. What shall world democracy mean to his race?

There never was a time more opportune than now for America to enfranchise the Red man!

Gertrude Bonnin, "Editorial Comment", The American Indian Magazine, Vol. VI, Winter, 1919, No. 4, 161-162.

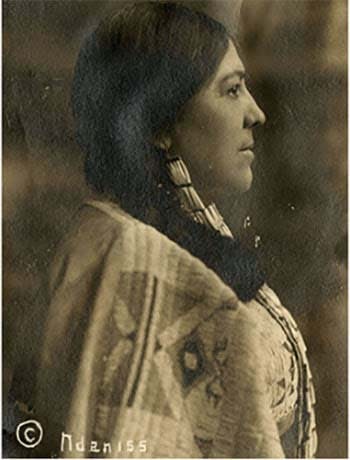

Zitkala-Ša (1876–1938) was a musician, a college graduate, and a member of the Yankton Dakota Sioux Nation. She adopted this name, which meant “red bird,” as an adult. She was also known as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin. She used both names in her writing. (Click here for her life story.)

Zitkala-Ša supported women’s rights and women’s suffrage. But her primary focus was US citizenship for Native Americans. The Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship to people born in the United States and those who became naturalized. But it excluded the great majority of Indigenous people because they lived on reservations. The federal government considered them citizens of their own sovereign nations. So they were not US citizens and could not vote in US elections. Nevertheless, thousands of Indigenous men served in the US military during World War I. Zitkala-Ša’s husband, Raymond Bonnin, was one of them.

After the war, the victors (the US and its allies) met in Paris to negotiate the terms for the losing side. Germany was required to give up all of its overseas empire. (Its many colonies in Africa may have been among the “little peoples” Zitkala-Ša referred to.) US President Woodrow Wilson presented negotiators with his plan for creating the League of Nations to prevent future wars. Many people around the globe viewed the Paris Peace Conference with optimism. They believed a safer, more just and democratic world lay ahead.

Thanks to the efforts of Zitkala-Ša and others, the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act granted US citizenship to Indigenous people. It was written in part to honor Native men’s service in the war. But the states still controlled voting, and many of the strategies used to prevent Black Americans from casting a ballot were used against Indigenous people. Over the next decades, individual states gradually passed laws to allow Native people to vote. But their voting rights were not fully guaranteed until the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Zitkala-Ša and her husband moved to Washington, DC, in 1917, and she became a well-known activist there. As the editor of American Indian Magazine, she contributed “editorial comments,” in which she argued for Native people’s rights. She attended and often spoke at meetings of non-Indigenous groups, including the National Women’s Party, founded by Alice Paul.

When she appeared at public meetings, Zitkala-Ša made a point of wearing traditional clothing and braiding her hair. She understood that her audiences had a view of Native people that was decades old. She dressed as they expected. But when she spoke, she brought them into the present by speaking about “the Indian woman of today.”

- clamoring

Making a noisy request.

- divers

Diverse, various.

- epoch

An important period of time, often related to historic events.

- opportune

Appropriate.

- Red man

A term used by early European settlers to describe America’s Indigenous people, whose skin color appeared red to them. Today it is considered a racial insult.

- supreme sacrifice

Dying while fighting for one’s country.

Why did Zitkala-Ša fight for US citizenship for Indigenous people? What is the link between citizenship and voting rights for men and women?

Why would Native men’s wartime service matter?

Zitkala-Ša wrote that the relatives of Indigenous soldiers who died in the war were seeking their “reward.” Why do you think she used that word?

Research the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act. How did the law affect the voting rights of Native men and women?

Research the role noncitizens play in the United States military today. If they die in action, are their families rewarded in some way? What do you think the US owes people who risk their lives defending the nation?

Indigenous women and men who lived on reservations became US citizens in 1924, but voting rights were slow to come. In 1948, Miguel Trujillo Jr., a World War II veteran, took actions on behalf of Native people in New Mexico. Research the court case Trujillo v. Garley.

Life Story: Mary Church Terrell

Mary Church Terrell was one of the leading Black suffragists of her time. She was born in Memphis, Tennessee, in the middle of the Civil War. She remained politically active well into her 80s, fighting for the rights of Black women and men.

Her birth name was Mary Church. Her parents had once been enslaved. But by the time of their daughter’s birth, they were both free and both owned successful small businesses. Robert Church was a real estate investor and later one of the South’s first Black millionaires. Louisa Ayers Church owned a popular hair salon. They insisted that their children receive the best possible education. They did not believe the Memphis schools were good enough.

Terrell went to the Antioch College Model School in Ohio when she was eight years old. As one of the few Black students at the school, she frequently faced racism, particularly from older students. She channeled her anger and humiliation into a world view that would shape her entire life. Because it pained her to be judged by the color of her skin, she committed herself to living a life of tolerance toward all races.

After graduating from high school, Terrell enrolled at Oberlin College. She was one of only two Black women in her class. After earning an undergraduate and a graduate degree, she taught French, writing, reading, and geology for two years at Wilberforce University, a private, historically Black university in Wilberforce, Ohio. She then taught Latin at the prestigious M Street Colored High School in Washington, DC. While there, she married fellow teacher Robert Terrell.

After her marriage, Terrell left the teaching profession for social reform work. In 1892, when she was still in her 20s, she founded the Colored Women’s League for Washington, DC. It provided night classes for women, childcare for working mothers, and kindergarten classes for Black children. In 1895 the Board of Education for Washington, DC, appointed Terrell their first Black member. The following year, she was named the first president of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), which unified the Black reform movement and promoted respect for all Black women. (The organization later changed its name to the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC)).

Suffrage was a primary focus of NACW and of Terrell’s volunteer work. “I can not recall a period in my life, since I heard the subject discussed for the first time as a very young girl, that I did not believe in woman suffrage with all my heart. When I was a freshman in college I wrote an essay entitled, ‘Resolved, There Should Be a Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution Granting Suffrage to Women.’” She believed that real change would be achieved only when women had the vote. She joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and built a lifelong friendship with Susan B. Anthony. She was one of the few Black members of the organization. She spoke out frequently to inform suffrage leaders that not all suffragists were white and that Black women needed to be included in the effort.

In 1900 Terrell was invited to give a major speech at the NAWSA convention, where she called on white women to support voting rights for Black women. The Boston Transcript published an editorial about the meeting and highlighted Terrell’s speech: “Perhaps the most striking and concise statement of the whole session was uttered when she declared . . . ‘The founders of this republic called heaven and earth to witness that it should be a government of the people, for the people and by the people; and yet the elective franchise is withheld from one-half of the citizens . . . because the word “people,” by an unparalleled exhibition of lexicographical acrobats, has been turned and twisted to mean all who are shrewd and wise enough to have themselves born boys instead of girls, or who took the trouble to be born white instead of black.”

Terrell was a powerful public speaker who greatly admired Frederick Douglass. During her time on the Washington, DC, school board, she encouraged schools to celebrate Frederick Douglass Day, a precursor to Black History Month. In 1908 she was invited to represent him at the 60th anniversary of the first women’s rights convention, held in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848. At that first convention, Douglass supported Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s resolution for women’s suffrage, which others at the meeting saw as much too bold and risky. “It was largely due to Frederick Douglass’ masterful arguments and matchless eloquence that the resolution passed in spite of the determined opposition of its powerful foes,” Terrell wrote in her 1940 memoir, A Colored Woman in a White World.

The Nineteenth Amendment was finally ratified on August 18, 1920. On August 26, it was certified by the Secretary of State and became law. Terrell joined the massive effort to immediately register women to vote, and millions of women cast their first ballots just weeks later, on November 3, 1920. But in the South, Black women were turned away from election sites, as were Black men. Local officials claimed they had not passed literacy tests or had failed to pay the poll tax. Regardless of the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments, Black Southerners were denied the right to vote.

In February 1921 the National Women’s Party (NWP) held a convention to decide on their next steps, since the right to vote had been won. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which Terrell had helped found, wanted the NWP to fight for the voting rights of Black women in the South. Alice Paul, the NWP leader, ignored the request. Paul had long said that if the NWP supported Black women’s rights, white Southern women would desert the organization. When the NAACP threatened to picket the NWP meeting, Terrell was allowed to speak to the NWP’s Resolutions Committee. She described the alarming realities faced by Black women in the Jim Crow South. “No woman in this country needs the ballot more than the colored women of the south. There they are the victims of lynching, [and] the convict lease System. . . . They are handicapped not only because they are women but because they are colored women. They bear the burden of color as well as of sex.”

Terrell recorded these words in A Colored Woman in a White World. But the stenographer who transcribed the original NWP meeting did not include her speech in the official notes. And the NWP did not adopt a resolution on behalf of Black women’s voting rights. One Black woman said Alice Paul had been “thoroughly hostile” to their requests. In the view of many, then and now, the suffrage movement was a campaign for and by white women. Terrell did not publicly complain about white attitudes—it was not her style. But she made sure to accurately describe her own role on behalf of women’s suffrage, as well as the determination and contributions of the many people of color who had fought for American women’s right to vote.

Terrell continued to defend the rights of Black people. In 1950, when she was 86, she sued a segregated Washington, DC, restaurant that had refused to serve her. To protest other racist businesses, she organized picket lines that continued for weeks or months at a time. Terrell died in July 1954, less than two months after the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education paved the way for far-reaching integration. At the time, she was still fighting against segregation in the nation’s capital, especially in schools and places of work.

- advocacy

Public support of a cause or promotion of an idea or opinion.

- Brown v. Board of Education

A 1954 Supreme Court case in which the court ruled that laws that allowed “separate but equal” education for students of different races were a violation of the Constitution.

- humiliation

Severe embarrassment.

- lexicographical acrobats

People who try hard to distort the meaning of words in order to support a point of view.

- ovation

Loud or prolonged applause.

- precursor

Something that comes before something else.

- segregation

Separation of people categories such as race, class, or ethnic group.

- suffrage

The right to vote. In Terrell’s time, the word often referred specifically to women’s voting rights.

How did the racism Terrell faced as a young student shape her outlook on life and her work as an educator and activist?

Terrell is most recognized for her suffrage work. Why is it important also to study her life and work after the Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, was passed?

How did both gender and race shape Terrell’s experience as an activist? How might her experience have differed from the white female or Black male activists around her?

The phrase “of the people, by the people, for the people” is from Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, though many people associate it with the nation’s founding documents. Why would Terrell quote this powerful phrase in arguing for women’s suffrage? How did she use it to address what she called lexicographical acrobats?

Compare the life stories of Mary Church Terrell and Nina Otero-Warren. What role do you think their families’ financial well-being played in these women’s later activism?

Terrell served as the mentor to Delta Sigma Theta, Howard University’s politically-minded sorority, and marched with them in the 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, DC. Imagine the conversation they might have had before the parade. What do you think Terrell might have said to these young women? Why would her encouragement or warnings matter?

Life Story: Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin

Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin was a member of the Turtle Mountain Ojibwe Nation. She was born in 1863 in what is today North Dakota and grew up outside Minneapolis, Minnesota. But she spent her adult life in Washington, DC, where she worked for women’s suffrage and Indigenous rights. She was one of the first two Native women to earn a law degree. (In this life story, she is referred to as Bottineau Baldwin to distinguish her from Marie Louise Baldwin, a Black suffragist in Boston.)

Her unusual journey began with her father. Jean Baptiste Bottineau was, like many of his family members, of mixed Ojibwe and French descent. He worked as a lawyer after his apprenticeship to a practicing attorney. Around 1890 the Turtle Mountain chiefs asked him to represent the tribe in land disputes with the federal government. He moved to Washington, DC, and brought his daughter with him as his law clerk.

Marie Bottineau Baldwin was then in her 20s. She had been married briefly to a white businessman named Fred S. Baldwin. Divorce was considered scandalous, so like many other divorced women, she said she was a widow. She worked with her father on cases involving the Ojibwe, also known as the Chippewa. But the idea of becoming a lawyer herself did not yet cross her mind.

Bottineau Baldwin worked with her father for 20 years. By 1911, he was elderly and ready to close his office. She had earlier met the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, who was impressed with her skills and knowledge. He offered her a job as a clerk in the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). She was the first Native woman to work in the BIA’s headquarters, where nearly everyone was white and male. Asked to submit a photograph for her personnel file, she provided a portrait of herself in Indigenous clothing. She had other photos, in which she wore western clothes. But she presented herself to the BIA as unmistakably and proudly Ojibwe.

At the time, many white Americans saw Native people as relics of the past, not modern people who worked in office buildings in the nation’s capital. Bottineau Baldwin, and other Native people in Washington, sought to change their thinking. They founded the Society of American Indians (SAI), and Bottineau Baldwin was one of its leaders. In 1912, several months after her father’s death, she enrolled at the Washington College of Law, the first law school to be founded by and for women. Her sense of herself, and her life’s work, was changing.

Washington College of Law did not accept Black women. Its students were white and fiercely political. The school was a hub of white suffragist fervor in the city, as Howard University was a hub of Black suffragism. Bottineau Baldwin enrolled at the age of 49, so she was older than other students. But the atmosphere at the school energized her and sharpened her political focus.

As she studied law, Bottineau Baldwin continued to work at the BIA. Florence Etheridge, a lawyer and recent Washington College graduate, was also on the staff. She was a member of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), which was planning a major suffrage parade in Washington, DC, on March 3, 1913. The parade was Etheridge’s idea, and she may have suggested Bottineau Baldwin for a float that parade organizer Alice Paul was hoping to include.

One goal of the suffrage parade was to highlight cultures where women had power. In many Native cultures, women were viewed as men’s equals, with a voice in tribal matters. Paul wanted a float that would emphasize their strength. One report said the float would carry “real Indian women in genuine ancient Indian costumes, loaned by the Smithsonian Institution.” Alice Paul asked Marie Bottineau Baldwin to create this float. But the idea for the float overlooked glaring facts: Native people faced government programs (like boarding schools) that sought to destroy their cultures. Most lived on reservations and were specifically denied US citizenship by the Fourteenth Amendment. The only Native people who could vote were men who had assimilated into the American mainstream and were therefore considered “civilized.”

Just a few days before the parade, the order of march was published in The Women’s Journal, a Boston newspaper. Several “gorgeous and imposing floats” were promised. One was devoted to “the primitive American woman, with a voice in tribal government.” Bottineau Baldwin wanted people to appreciate both the traditional and the modern in Indigenous culture. But the float was focused on the past, not the present or the future, and she chose not to work on it. Instead, she wore the cap and gown of the Washington College of Law and marched with her school to support women’s right to vote.

In 1914 Bottineau Baldwin graduated with honors and became one of America’s first two Indigenous woman lawyers. She remained at Washington College of Law and earned a master’s degree. She did not practice law after graduating, continuing instead to work at the BIA. She came face to face with the blatant racist thinking common in the United States during the Jim Crow period. President Woodrow Wilson mandated that the federal government’s work force, which included many Black people, be segregated. Indigenous people were not seen as Black, but they were not seen as fully white either. Bottineau Baldwin worried that Native people might be categorized with Black people, which would threaten her job at the BIA. In a private letter to a fellow leader of the Society of American Indians, she seemed to side with the president’s segregation policy. She wrote that Black people should not be hired by the BIA to work on reservations or in Indian schools. “The negro,” she wrote, “is immoral—dangerous!”

Bottineau Baldwin became caught up in tensions between the two organizations she was committed to serving. The policy of the BIA, where she worked, was that Indigenous people should assimilate. They should blend in, speak English, put aside their Native culture and clothes, and leave the reservations. Those who did were called civilized. (When Bottineau Baldwin submitted the photo of herself in Ojibwe dress for her BIA personnel files, she was making a courageous statement.)

But members of SAI, where Bottineau Baldwin was on the advisory board, believed assimilation would destroy Indigenous culture. They criticized the BIA and Native people who worked there, including Bottineau Baldwin. She certainly wanted Indigenous traditions to survive, but she also believed in modern life. She may have seen that the old ways were already vanishing. She owned a sizable collection of Native-made baskets, jewelry, and clothing, which may have been her attempt at preserving a vanishing culture. She mostly withdrew from the SAI and remained at the BIA. The reasoning for this decision is unclear, but she stayed with the BIA until she retired in 1932.

- advisory board