Presidential Use of

Military Force

Presidential Use of

Military Force

Unit Introduction

Examine presidential powers in wartime and consider presidential use of military force through a case study of the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF).

The US Constitution grants Congress the sole power to declare war, but Congress has not declared war since World War II.

The United States has fought in many wars since the 1940s under laws known as Authorizations for Use of Military Force, or AUMFs.

The AUMF enacted after the attacks of 9/11 was broadly written, and has been used against terrorist enclaves beyond Afghanistan, the original target country.

Efforts in Congress to repeal the 2001 AUMF began almost immediately, at first with limited support. The support for repeal increased after the US carried out extended military interventions but the AUMF remains in effect.

Who is responsible, Congress or the president, for the decision to go to war? This issue has generated many decades of debate. The Constitution clearly gives Congress the sole power to declare war, but since World War II, presidents have gained more and more control over this decision.

This unit examines the presidential authority to use military force, from the wording of the Constitution through the early 21st century. While the unit's video, Presidential Power in Wartime, homes in on the 20th-century conflicts in Korea and Vietnam, the focus of the resources and life stories is the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) that followed 9/11. This AUMF led to the war in Afghanistan and dozens of antiterrorist actions in the Middle East and Africa. Unit resources explore the history of war-making since President Harry S. Truman, the language of the Constitution and the 1973 War Powers Act, the events of 9/11, the writing of the AUMF, its broad application over time, and ongoing repeal efforts. President George W. Bush and Representative Barbara Lee, the only member of Congress who voted against the AUMF, are the life story subjects.

The unit was developed in the late summer and fall of 2021, as the war in Afghanistan ended but the AUMF remained in effect. So it tells an unfinished story. Throughout the unit, activities are suggested to help students do research to bring the issues up to date.

What role should the president and Congress play in the decision to go to war?

What are the risks of giving presidents too much war-making power?

How do the events of 9/11 continue to shape American policy and American lives?

The items in this unit can be used individually or collectively and in any order that works for your classroom. Some teachers may choose to introduce the life stories first, putting key players at the forefront before students explore the rest of the story. Others may want students to dive into specific primary resources to glean as much information as possible before viewing the wider narrative. The unit has been designed so that either approach works.

This unit examines how the attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, led to the long war in Afghanistan, and it specifically focuses on how the White House and Congress authorized the war. Understanding how Americans in general, and especially elected officials, were feeling and thinking after the attacks is central to the unit.

Today’s students have no memory of 9/11. Some may know little or nothing about it. But others may have a personal, even painful, connection to the events of that day and the war that followed. Before you begin this unit, you might want to have a class discussion, or do a writing activity, that will tell you what your students know, think, and feel about this shocking chapter in America’s recent history. The resource titled "September 11, 2001" includes photographs of the 9/11 attacks and raises questions about the emotional impact of that day, as a prelude to the government’s responses presented in the resources related to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF). An introductory activity will help you decide if and how you need to tailor these materials, and these two resources specifically, to the needs of your students.

Some teachers will choose to select one or more of the items in this unit, and incorporate them into their own existing curriculum. The items are designed with this selective use in mind.

But this unit is also based on a chronology that follows a story line. If you would like to use all the unit materials as a group, it makes sense to first watch the video, Presidential Power in Wartime, with the whole class. It introduces the post-World War II era, when wars have not been declared by Congress and presidents have gained more power.

After viewing the video, assign each of the remaining resources to a small group, and ask all the groups to read the life stories. Then, as a class, using the Constitution as a baseline, generate a timeline focused on the period from 1950 to the present. Discuss the issue of war powers in this period. How has presidential power grown? Does the president currently have too much power over war decisions? How much power is the right amount to enable presidents to fulfill their constitutional duties?

Click on the materials below to begin exploring presidential use of military force.

- Video: Presidential Power in Wartime

This video examines the powers of the president and Congress in times of war.

Curriculum Connections: war powers, the US Constitution, the Vietnam War

- Resource: The Power to Wage War

This resource excerpts the US Constitution and the 1973 War Powers Act which specify powers of both the Congress and the president in waging war.

Curriculum Connections: the US Constitution, the War Powers Act

- Resource: September 11, 2001

This resource contains images and video from September 11, 2001.

Curriculum Connections: terrorism, 9/11

- Resource: 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF)

This resource pairs passages from the White House draft of the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) with the congressional revision to that text.

Curriculum Connections: war on terror, Congress, war powers

- Resource: Actions Taken Under the 2001 AUMF

This resource outlines a selected range of the many actions in many countries that have been taken under the authority of the 2001 AUMF.

Curriculum Connections: war on terror, war in Iraq, war in Afghanistan

- Resource: The Effort to Repeal the 2001 AUMF

This resource explores 2019 efforts to repeal the 2001 AUMF.

Curriculum Connections: war powers, Congress, war on terror

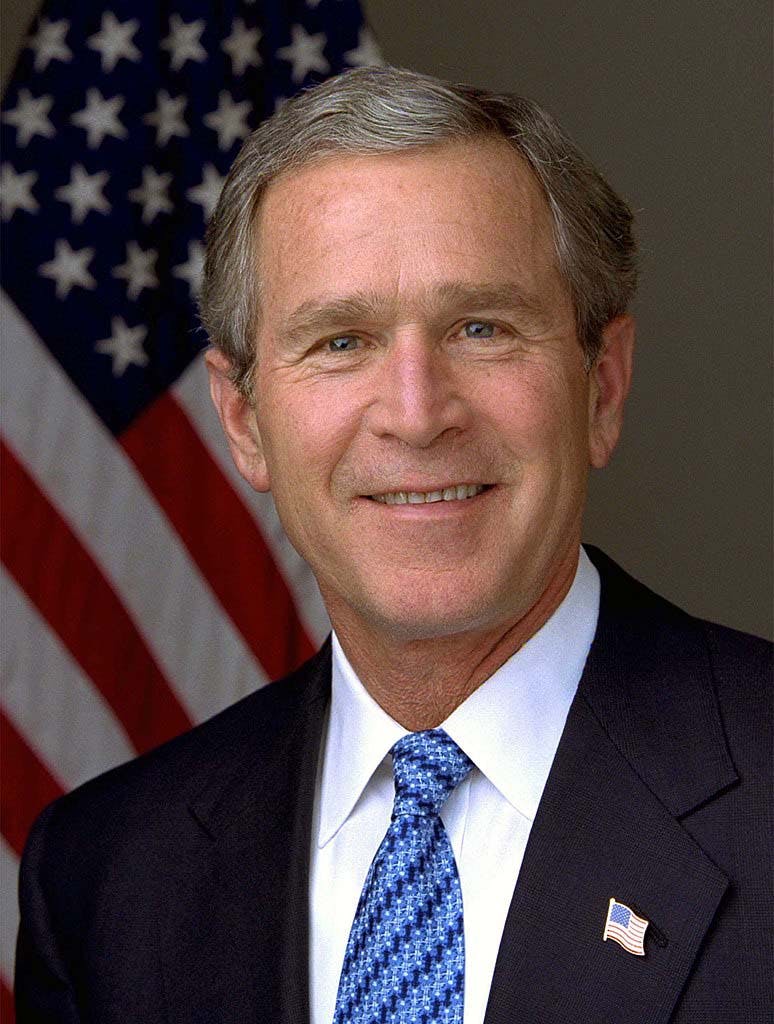

- Life Story: President George W. Bush

The story of the president who led the country during and immediately following the attacks on September 11, 2001.

Curriculum Connections: the presidency, war on terror, war powers

- Life Story: Representative Barbara Lee

The story of the only member of Congress to vote against the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force.

Curriculum Connections: Congress, war on terror, war powers

Video: Presidential Power in Wartime

This video examines the powers of the president and Congress in times of war.

This video was created by the New-York Historical Society in collaboration with Makematic.

Historian Michael Beschloss and filmmaker Ken Burns explore how the United States has gone to war over time. The video opens with a review of the founders’ concerns that presidents would have too much power, especially when it came to starting a war. In writing the US Constitution, they specifically and clearly gave war-making power to Congress, but Congress has not declared war since the beginning of World War II. Beschloss and Burns examine American wars since that time, and the reelection concerns that often drive presidents’ war decisions. With a special focus on Vietnam, they discuss the authorization for war that was based on an alleged incident in the Tonkin Gulf, the role of changing public opinion, and the decades of government deception in its public statements about the war.

David M. Rubenstein is Co-Founder and Co-Chairman of The Carlyle Group, one of the world’s largest and most successful private investment firms. Established in 1987, Carlyle now manages $301 billion from 26 offices around the world.

Mr. Rubenstein is Chairman of the Boards of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the Council on Foreign Relations, the National Gallery of Art, and the Economic Club of Washington; a Fellow of the Harvard Corporation; a Trustee of the University of Chicago, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins Medicine, the Institute for Advanced Study, the National Constitution Center, the Brookings Institution, and the World Economic Forum; and a Director of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, among other board seats.

Mr. Rubenstein is a leader in the area of Patriotic Philanthropy, having made transformative gifts for the restoration or repair of the Washington Monument, Lincoln Memorial, Jefferson Memorial, Monticello, Montpelier, Mount Vernon, Arlington House, Iwo Jima Memorial, the Kennedy Center, the Smithsonian, the National Archives, the National Zoo, the Library of Congress, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Mr. Rubenstein has also provided to the U.S. government long-term loans of his rare copies of the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th Amendment, the first map of the U.S. (Abel Buell map), and the first book printed in the U.S. (Bay Psalm Book).

Mr. Rubenstein is an original signer of The Giving Pledge; the host of The David Rubenstein Show and Bloomberg Wealth with David Rubenstein; and the author of The American Story, How to Lead, and The American Experiment.

Michael Beschloss is an American historian specializing in the history of the presidency. He is the author of Presidents of War: The Epic Story, From 1807 to Modern Times, as well as numerous other books.

Ken Burns is a documentary filmmaker with 40 years of experience. Among dozens of documentary series exploring American culture and history, he produced The Vietnam War, an 18-hour film series made in 2017.

Watch Presidential Leadership, the video in Unit 1, and this video, Presidential Power in Wartime. Analyze the process that led from the Truman Doctrine to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. How did Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson see their wartime power after World War II? How did their actions and judgments about their war powers connect to the Truman Doctrine?

Research the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. How did it come to be passed? What powers did it give the president? Why is it now seen as too open-ended?

Resource: The Power to Wage War

Excerpts from the US Constitution and the 1973 War Powers Act that specify powers of both Congress and the president in waging war.

The Congress shall have Power To . . . declare War.

Only Congress has the power to declare war.

U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 11.

The Congress shall have Power To . . . declare War.

U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 11.

The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.

The president has the power to direct the military during wartime.

U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 1.

The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.

U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 1.

SEC. 2 (a) It is the purpose of this joint resolution to fulfill the intent of the framers of the Constitution of the United States and insure that the collective judgement of both the Congress and the President will apply to the introduction of United States Armed Forces into hostilities, or into situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances, and to the continued use of such forces in hostilities or in such situations.

The goal is to reassert the war powers of Congress as stated in the Constitution and to insure that Congress and the president will decide together when US forces should go to war.

(c). The constitutional powers of the President as Commander-in-Chief to introduce United States Armed Forces into hostilities, or into situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances, are exercised only pursuant to (1) a declaration of war, (2) specific statutory authorization, or (3) a national emergency created by attack upon the United States, its territories or possessions, or its armed forces.

The president can deploy the US military only if there is a declaration of war or specific Congressional permission, or if the United States has been attacked.

War Powers Resolution, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/warpower.asp.

SEC. 2 (a) It is the purpose of this joint resolution to fulfill the intent of the framers of the Constitution of the United States and insure that the collective judgement of both the Congress and the President will apply to the introduction of United States Armed Forces into hostilities, or into situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances, and to the continued use of such forces in hostilities or in such situations.

(c). The constitutional powers of the President as Commander-in-Chief to introduce United States Armed Forces into hostilities, or into situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances, are exercised only pursuant to (1) a declaration of war, (2) specific statutory authorization, or (3) a national emergency created by attack upon the United States, its territories or possessions, or its armed forces.

War Powers Resolution, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/warpower.asp.

In writing the US Constitution, the founders gave Congress the crucial power to declare war. Congress is a large body of people elected by the public. The founders believed the collective judgment of the House of Representatives and the Senate would reflect the needs and opinions of most Americans. They chose not to give the president war-making powers because they feared that a single person could easily decide to go to war for the wrong reasons.

The founders were also concerned about giving too much power to the military. So the Constitution names the president as commander in chief of the armed forces during wartime. The president is an elected official and a civilian, and therefore, the founders believed, more representative of the will of the people.

After World War II, presidents became more assertive in starting wars, and Congress largely deferred to the chief executive, from President Harry S. Truman’s deciding to wage the Korean War to Lyndon B. Johnson sending US ground troops to fight in the Vietnam War. That war was long, cost many lives, and failed to achieve its goal of ending communist governance in Vietnam. Many Americans believed the increasing war power of the president needed to be curtailed. In 1973, Congress passed the War Powers Act, over President Nixon’s veto, to strengthen the role of Congress in decisions to go to war.

The US Constitution specifies the powers of both the Congress and the president, in language meant to be clear and straightforward. Article I grants Congress the sole power to declare war.

By the terms of Article II, the president commands the armed forces, as well as the state militias, during wartime. Today the term “state militia” refers primarily to the National Guard.

The War Powers Act is also known as the War Powers Resolution. Rather than creating a hard separation of powers, it depended on “the collective judgment of both the Congress and the President.” It also specified when the president’s power as commander in chief could be used to send US armed forces into hostile or potentially hostile situations. This language went well beyond the presidential powers specified in the Constitution.

- declare war

To formally state that the United States is at war.

- hostilities

Armed aggression.

- imminent

About to happen.

- joint resolution

A decision agreed to and passed by both houses of Congress.

- service of the United States

Serving to defend the nation during wartime.

- statutory authorization

Legislation passed by Congress that authorizes the president’s action.

- wage war

To carry out a war.

According to the terms of Article I, what was Congress not allowed to do?

According to the terms of Article II, what was the President not allowed to do?

What are the main differences between the language of the Constitution and the language of the War Powers Act? Which document gave the president more power?

Research the history of the War Powers Act. What were the arguments for and against its passage in Congress? Why did President Nixon try to veto the bill?

Some members of Congress would like to repeal the War Powers Act. Research their arguments and their plans for replacing it.

Resource: September 11, 2001

Images and a video from September 11, 2001.

Note to teachers: Before introducing this resource, please consider doing the introductory activity to determine your students’ personal understanding of and experience with 9/11.

President Bush Addresses the Nation from the Oval Office. September 11, 2011. C-SPAN.

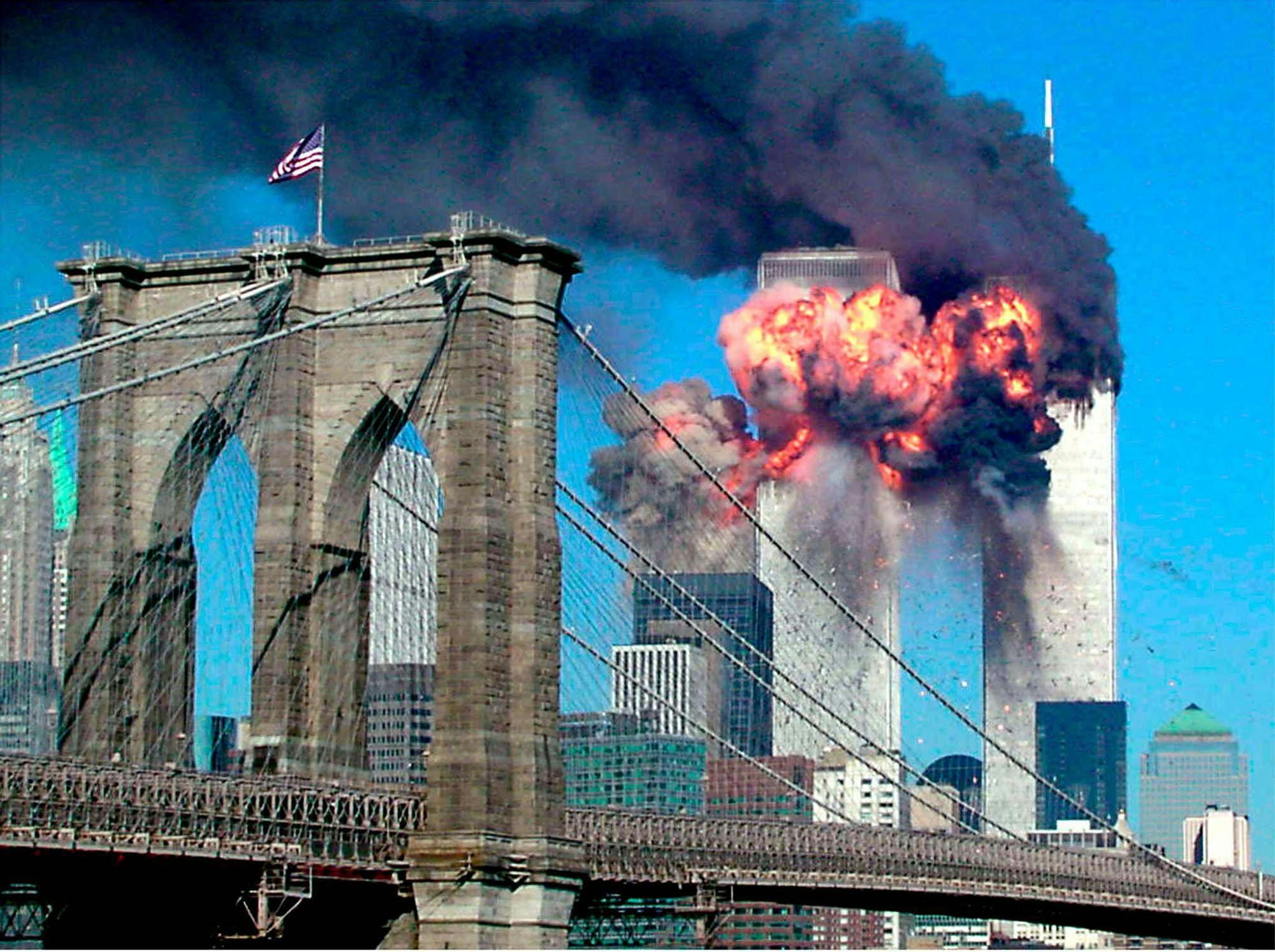

On the morning of September 11, 2001, four commercial US airplanes were hijacked in flight. The 19 hijackers, later identified as members of the terrorist group al Qaeda, were on a suicide mission. They flew two of the planes into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, just as people were starting their work day. The north tower was hit at 8:46 a.m. The second plane hit the south tower at 9:03.

At 9:37 a.m., the third plane hit the Pentagon, headquarters of the US Department of Defense, located just outside Washington, DC.

At 9:59, the south tower collapsed.

Minutes later, at 10:03, the fourth plane crashed in Pennsylvania. Passengers had learned from cell phone conversations that the nation was under attack and had stormed the hijackers. The target of the fourth plane was either the White House or the US Capitol.

At 10:28, the north tower collapsed.

That evening, President George W. Bush spoke to the nation from the Oval Office.

September 11, 2001, was the first time the United States had been directly attacked since the War of 1812. The bombing of Pearl Harbor, a military target, brought the United States into World War II. But Hawaii was a territory in 1941, not located on the mainland and not yet a state.

Nearly 3,000 people died on 9/11, including passengers on the planes, people who were in the buildings, first responders, and the hijackers.

The photo of the World Trade Center in flames was taken shortly after the second tower was hit. The Brooklyn Bridge is in the foreground.

The damaged clock was found among the debris from the attacks, all of which was taken to a landfill on Staten Island. There the material was carefully sifted and examined by the FBI in a search for evidence and meaningful mementoes. An FBI agent donated the clock to the New-York Historical Society.

The flag-raising photo was taken around 4:00 or 5:00 on the afternoon of 9/11. The emotional event was described by another photographer, Christian Parley: The three firefighters, William Eisengrein, George Johnson and Daniel McWilliams, had discovered a US flag on the back of a yacht inside a boat slip at the World Financial Center. They took the banner and decided to raise it as a statement of loyalty and resilience.

The photo of the Pentagon was taken after a huge flag was unfurled on September 12, as first responders searched for victims.

The video is President Bush’s televised address to the nation on the night of September 11, nearly 12 hours after the first plane hit the World Trade Center.

- al Qaeda

A militant Islamist organization founded in the late 1980s by Osama bin Laden. Al Qaeda means “the base.” The word “Islamist” refers to groups that advocate violent action in support of Islam, not to the religion of Islam itself.

- first responders

People trained to respond to emergencies, including police officers, firefighters, and emergency medical technicians (EMTs).

- hijack

To illegally take control of an airplane or other vehicle.

- intelligence

Information of military or political value.

- Pentagon

The five-sided headquarters of the US Department of Defense.

- terrorist

A person who uses unlawful violence to achieve political aims.

- World Trade Center

A complex of seven buildings in lower Manhattan, opened in 1973. The two tallest buildings, often called the twin towers, were struck by aircraft on 9/11 and collapsed soon after. A new tower known as One World Trade Center has been built at the site, as well as the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.

Before 9/11, the United States had not been attacked since the War of 1812. What emotions do you think Americans felt that day as they watched the uninterrupted news on television?

Compare the photos of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. In what ways are these sites different?

Why is the damaged but still readable clock, stopped at 9:04, so powerful? Why do you think it is now in the New-York Historical Society’s collection? What makes it museum-worthy?

The flag photo has been reprinted many, many times. Why do you think it became iconic? Why would Americans find it meaningful?

In his televised address, how did President Bush explain why the terrorists carried out the attacks? What questions do you have about the motives behind 9/11? Did the president address them?

How would you summarize President Bush’s speech in a few phrases? What topics did he address? What did he leave out? What was his demeanor?

Ask adults who lived through and remember 9/11 to look at the photos and describe their reactions to that day. What were they thinking and feeling? What questions were on their minds then? What did they think of the war?

Research the World War II photo of the flag-raising at Iwo Jima. How is it similar to the photo of the 9/11 flag-raising? What do these photos suggest about the meaning of the American flag in times of national sorrow and anger?

Compare President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “day of infamy” speech after Pearl Harbor to President Bush’s address on 9/11. Focus especially on the role played by Congress, both at the speech itself and in each president’s references. What might explain any differences you see?

For a video of President Roosevelt’s speech, click here. For the text of President Roosevelt’s speech, click here. For the text of President Bush’s speech, click here and scroll to page 57 of the text.

Resource: Actions Taken Under the 2001 AUMF

This resource outlines a selected range of the many actions in many countries that have been taken under the authority of the 2001 AUMF.

Interactive Map of Select Military Actions

Afghanistan

On October 7, 2001, the US military began air strikes, using armed drones, against al Qaeda and Taliban forces in Afghanistan. US troops arrived 12 days later. Detention facilities were opened for al Qaeda prisoners and suspects at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

NATO forces arrived in Afghanistan in December 2001 under a United Nations mandate to prevent the country from ever again being a safe haven for terrorism. Soldiers from NATO countries, including the United States, and the Afghan military formed a coalition to find and defeat al Qaeda. In 2003, NATO assumed command of the coalition in Afghanistan, and it has remained involved in US counterterrorism activities in other countries.

Horn of Africa

Beginning in 2003, US troops were deployed to Djibouti for action against al Qaeda and other terrorist groups in the region called the Horn of Africa. The countries located on the Horn are Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, and the independent region of Somalia known as Somaliland.

Iraq and Syria

The Iraq War began in 2002 under a separate Authorization for Use of Military Force. Its goal was to eliminate weapons of mass destruction thought by some to be held by the regime of Saddam Hussein. But because terrorist groups linked to al Qaeda were known to be in Iraq, in 2004 the United States began to pursue these groups in Iraq under the authority of the 2001 AUMF.

Beginning in 2014, US troops were deployed to Iraq and Syria to combat the rise of an al Qaeda-linked terrorist group called the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). It is sometimes called the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), but the area called the Levant includes several countries in addition to Syria. So ISIL more accurately conveys the organization’s intended reach.

Yemen

In 2002, training and support services for US military personnel began in Yemen. Antiterrorism actions began in 2003 and continued in 2014 and after, during the rise of ISIL.

Somalia

Beginning in 2012, US forces take military action against al-Shabaab, a militant organization, based in Somalia, with ties to al Qaeda.

Libya

In 2015, the US military began conducting drone strikes against ISIL in Libya.

Niger

In 2017, ISIL attacked US forces that were in support roles in Niger. The US and Niger military responded with force in self-defense.

Support Locations

The US military established training facilities, supply depots, and/or airfields in a number of countries, including the Philippines, Georgia, Yemen, Turkey, Jordan, and Cameroon.

Afghanistan

On October 7, 2001, the US military began air strikes, using armed drones, against al Qaeda and Taliban forces in Afghanistan. US troops arrived 12 days later. Detention facilities were opened for al Qaeda prisoners and suspects at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

NATO forces arrived in Afghanistan in December 2001 under a United Nations mandate to prevent the country from ever again being a safe haven for terrorism.

Soldiers from NATO countries, including the United States, and the Afghan military formed a coalition to find and defeat al Qaeda. In 2003, NATO assumed command of the coalition in Afghanistan, and it has remained involved in US counterterrorism activities in other countries.

Horn of Africa

Beginning in 2003, US troops were deployed to Djibouti for action against al Qaeda and other terrorist groups in the region called the Horn of Africa. The countries located on the Horn are Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, and the independent region of Somalia known as Somaliland.

Iraq and Syria

The Iraq War began in 2002 under a separate Authorization for Use of Military Force. Its goal was to eliminate weapons of mass destruction thought by some to be held by the regime of Saddam Hussein. But because terrorist groups linked to al Qaeda were known to be in Iraq, in 2004 the United States began to pursue these groups in Iraq under the authority of the 2001 AUMF.

Beginning in 2014, US troops were deployed to Iraq and Syria to combat the rise of an al Qaeda-linked terrorist group called the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). It is sometimes called the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), but the area called the Levant includes several countries in addition to Syria. So ISIL more accurately conveys the organization’s intended reach.

Yemen

In 2002, training and support services for US military personnel began in Yemen. Antiterrorism actions began in 2003 and continued in 2014 and after, during the rise of ISIL.

Somalia

Beginning in 2012, US forces take military action against al-Shabaab, a militant organization, based in Somalia, with ties to al Qaeda.

Libya

In 2015, the US military began conducting drone strikes against ISIL in Libya.

Niger

In 2017, ISIL attacked US forces that were in support roles in Niger. The US and Niger military responded with force in self-defense.

Support Locations

The US military established training facilities, supply depots, and/or airfields in a number of countries, including the Philippines, Georgia, Yemen, Turkey, Jordan, and Cameroon.

In the days after 9/11, investigations by the United States and its allies determined that al Qaeda had organized the attacks. The group’s leader, Osama bin Laden, was in Afghanistan under the protection of the Taliban, an Islamist group that ruled the country. “Islamist” refers to a militant, fundamentalist form of Islam. The faith itself is not militant and is followed by almost two billion Muslims, a quarter of the world’s population. President Bush repeatedly made clear that neither Islam nor Muslims in general were responsible for 9/11 and that they should not be punished for the actions of a few extremists.

The president vowed to conquer those who were responsible, and the 2001 AUMF gave him broad authority to take military action. Under this AUMF, four American presidents have pursued al Qaeda and related terrorist organizations for more than two decades and into various parts of the world.

Many actions, in many countries, have been taken under the authority of the 2001 AUMF, including combat and support activities. Under the terms of the War Powers Act, the president must regularly notify Congress of any actions taken under the AUMF. Some of these reports are published, but others are classified. As a result, it is not possible to provide an accurate list of all the steps taken by the White House under the authority of the AUMF.

This resource shows the geographic and chronological range of selected military actions taken under the 2001 AUMF through 2021. It is not a primary source document, but a secondary source, developed for this curriculum to simplify a broad, complex, ongoing story.

The interactive map shows the select locations. If you click on a number, details about that location and the actions taken will appear. The colors on the map indicate types of climate and terrain. The same information is provided in list form below.

The collection of photographs provides visual examples of these actions. The photo of coalition forces was taken during the search for Osama bin Laden in Tora Bora, a complex of caves in Afghanistan that served as a stronghold for al Qaeda and the Taliban. The picture of the graffiti shows local reaction to drone attacks by the Americans. The photo of the 1st Cavalry soldiers was taken after Osama bin Laden was killed but while the war against al Qaeda and the Taliban continued.

- al Qaeda

A militant Islamist organization founded in the late 1980s by Osama bin Laden. Al Qaeda means “the base.”

- al-Shabaab

An insurgent Islamist group, formed in the early 2000s, that has been working to establish an Islamic state in Somalia. Al-Shabaab means “the Youth.”

- drone

An aircraft that flies without a pilot and is controlled remotely from the ground. Drones may be unarmed, or they may carry bombs to drop on military targets.

- Horn of Africa

The peninsula on the east coast of Africa, shaped like the horn of a rhinoceros.

- Islam

The religious faith practiced by Muslims around the world for centuries.

- Islamic

Related to the Muslim religion.

- Islamist

Related to groups advocating Islamic militancy or fundamentalism.

- Levant

A term from the French language, referring to the countries of Cyprus, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey.

- NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Alliance, formed in 1949. Members include the United States, Canada, and 28 European countries who agree to respond collectively if one member country is attacked.

- Saddam Hussein

The president of Iraq from 1979 to 2003.

- Taliban

A movement of fundamentalist Muslims that set up an Islamic state in Afghanistan in 1996. The Taliban was overthrown when the United States invaded after 9/11. It returned to power after the 2021 withdrawal of US troops.

Why was it necessary to link terrorist groups to al Qaeda before engaging them in combat?

Closely examine the interactive map or review the list of actions. What do they tell you about the geographic extent of the US effort to retaliate for 9/11? How does this information relate to the original and the final language of the AUMF?

How did the actions under the 2001 AUMF change over time? How did activities expand in 2003? What happened in 2012? How and why did the US antiterrorism efforts change in 2014?

Search recent online articles for stories about current US actions against terrorism. Search terms might include ISIS, ISIL, Islamic State, and drone. Find the most recent article and summarize it. How does it fit in to the story of 9/11?

Using online sources, determine the approximate distance from Afghanistan to Cameroon and the distance from Georgia to Somalia. Then determine the approximate distance from Washington, DC, to San Francisco, CA, and from Fargo, ND, to Corpus Christi, TX. How does the size of the United States compare to the size of areas where US military actions have taken place? Does the geographic extent violate the terms of the AUMF? Do you think it goes beyond the original intent of Congress?

Resource: The Effort to Repeal the 2001 AUMF

A collection of documents exploring the 2019 efforts to repeal the 2001 AUMF.

MS. [BARBARA] LEE (D-CA). On September 14, 2001, 3 days after the horrific attacks, I was the only ``no'' vote in Congress for the 2001 AUMF. It was an authorization that I knew would provide a blank check for the President, any President, to wage a war anywhere, any time, and for any length. In the last 18 years, it has been used by three consecutive administrations to wage war at any time, at any place, without congressional oversight or authorization.

In the almost 18 years since its passage, it has been cited 41 times in 19 countries to wage war with little or no congressional oversight.

The AUMF has reportedly been invoked to deploy troops in Syria, Yemen, Somalia, Libya, and Niger. We know that this is far beyond what Congress intended when it was passed in 2001 in the days after the terrible attacks of 9/11.

I was the only member of Congress to vote against the 2001 AUMF. I knew it gave the president too much power. Now, 18 years later, it has been used far beyond what Congress intended. So I have drafted this amendment.

MR. [MICHAEL] McCAUL (R-TX). Madam Chair, I rise in strong opposition to this amendment. It simply lists complaints about the 2001 authorization for the use of military force while avoiding the serious work of proposing an improved replacement. . . .

The author of this amendment has also inserted an outright repeal of the 2001 AUMF into this year's Defense appropriations bill, which would make all counterterrorism operations globally illegal. That is reckless because AUMF provides the necessary legal authority to confront ongoing deadly threats against our homeland. . . .

It is incorrect to assert, as this amendment does, that the 2001 AUMF is a blank check for any President to wage war at any time and at any place. The AUMF has been interpreted as covering al-Qaida, the Taliban, and “associated forces.” And while that interpretation is sometimes broad, it can’t be stretched to cover just anything. . . .

As the Director of National Intelligence has testified, al-Qaida and ISIS maintain transnational networks actively committed to our destruction. . . . Until we have new authorities in place to combat the real and dynamic threats to American lives and safety, we need to focus on responsibly using the authorities we have, not just complaining about their imperfections.

I oppose this amendment. Without the 2001 AUMF, we have no legal way to fight terrorism, even though threats continue. The 2001 AUMF has not been used beyond what Congress intended. It continues to authorize actions against those behind the 9/11 attacks, who are still committed to our destruction. The amendment complains about the 2001 AUMF without offering a better alternative.

H.R. 2500 - 116th Congress.

MS. [BARBARA] LEE (D-CA). On September 14, 2001, 3 days after the horrific attacks, I was the only ``no'' vote in Congress for the 2001 AUMF. It was an authorization that I knew would provide a blank check for the President, any President, to wage a war anywhere, any time, and for any length. In the last 18 years, it has been used by three consecutive administrations to wage war at any time, at any place, without congressional oversight or authorization.

In the almost 18 years since its passage, it has been cited 41 times in 19 countries to wage war with little or no congressional oversight.

The AUMF has reportedly been invoked to deploy troops in Syria, Yemen, Somalia, Libya, and Niger. We know that this is far beyond what Congress intended when it was passed in 2001 in the days after the terrible attacks of 9/11.

MR. [MICHAEL] McCAUL (R-TX). Madam Chair, I rise in strong opposition to this amendment. It simply lists complaints about the 2001 authorization for the use of military force while avoiding the serious work of proposing an improved replacement. . . .

The author of this amendment has also inserted an outright repeal of the 2001 AUMF into this year's Defense appropriations bill, which would make all counterterrorism operations globally illegal. That is reckless because AUMF provides the necessary legal authority to confront ongoing deadly threats against our homeland. . . .

It is incorrect to assert, as this amendment does, that the 2001 AUMF is a blank check for any President to wage war at any time and at any place. The AUMF has been interpreted as covering al-Qaida, the Taliban, and “associated forces.” And while that interpretation is sometimes broad, it can’t be stretched to cover just anything. . . .

As the Director of National Intelligence has testified, al-Qaida and ISIS maintain transnational networks actively committed to our destruction. . . . Until we have new authorities in place to combat the real and dynamic threats to American lives and safety, we need to focus on responsibly using the authorities we have, not just complaining about their imperfections.

H.R. 2500 - 116th Congress.

Representative Barbara Lee, a California Democrat, was the only member of Congress to vote against the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force. She has always believed the language gives the president unconstitutional power over war-making, and she has regularly introduced legislation to repeal it. (For many years she has also worked to repeal the 2002 AUMF that authorized the Iraq war, which ended in 2011.)

In 2019, as Congress prepared the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, Rep. Lee added an amendment calling for the 2001 AUMF to “sunset,” meaning to expire after a specified period of time. It was cosponsored by Rep. Max Rose, a New York Democrat. This resource includes the full text of the proposed amendment and excerpts of the debate. (The complete debate was printed in the Congressional Record for July 11, 2019.) The video of the debate can be viewed here (9:35:00 to 9:47:14).

Rep. Lee also introduced another amendment, calling for repeal of the 2002 Iraq War AUMF. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 was passed by the House with the two repeal amendments included, but both amendments were dropped by the Senate.

As of September 2021, Rep. Lee continues to work to repeal both the 2001 and 2002 AUMFs.

- amendment

A change or addition to a piece of legislation.

- blank check

Complete freedom to act as one chooses.

- counterterrorism

Related to measures meant to combat or prevent terrorism.

- deploy

To move troops or equipment into position for military action.

- National Defense Authorization Act

Annual legislation by which Congress establishes the priorities and budget of the Department of Defense.

- operations

Military actions in response to a developing situation.

- repeal

To revoke or cancel.

What reasons did the amendment list for repealing the 2001 AUMF? Which one seems most important to you?

Why did Rep. Lee think the 2001 AUMF had been a “blank check” for several presidents? Why did Rep. McCaul disagree?

The debate includes a Democrat and a Republican. What points did the two agree on? Where did they disagree?

Research the current status of the 2001 AUMF. Has it been repealed? Replaced? If it is still in effect, how is it now being applied?

Some Republicans and Democrats in Congress believe the 1973 War Powers Act should be revised. Search a newspaper archive for articles about how Republicans, Democrats, or the president would like to change this law.

Life Story: George W. Bush

The story of the president who led the country during and immediately following the attacks on September 11, 2001.

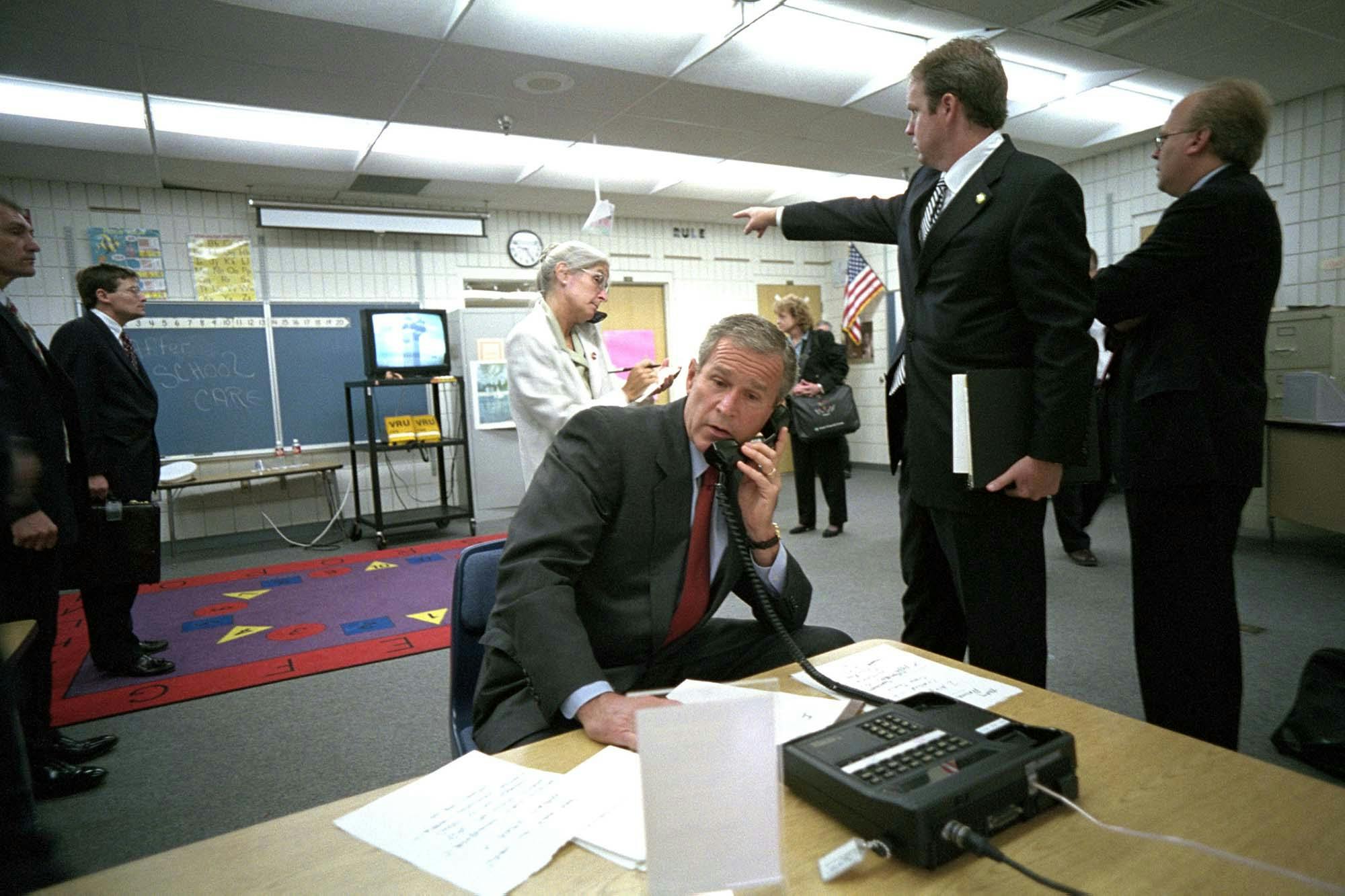

On the morning of September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush was in Sarasota, FL, to visit a second-grade class at Emma E. Booker Elementary School. He and his aides arrived at the school at 8:50. A staff member of the National Security Council told them that an airplane had flown into one of the twin towers of New York City’s World Trade Center—the one known as the “north tower.” Assuming it was a tragic accident, the president went ahead with his schedule.

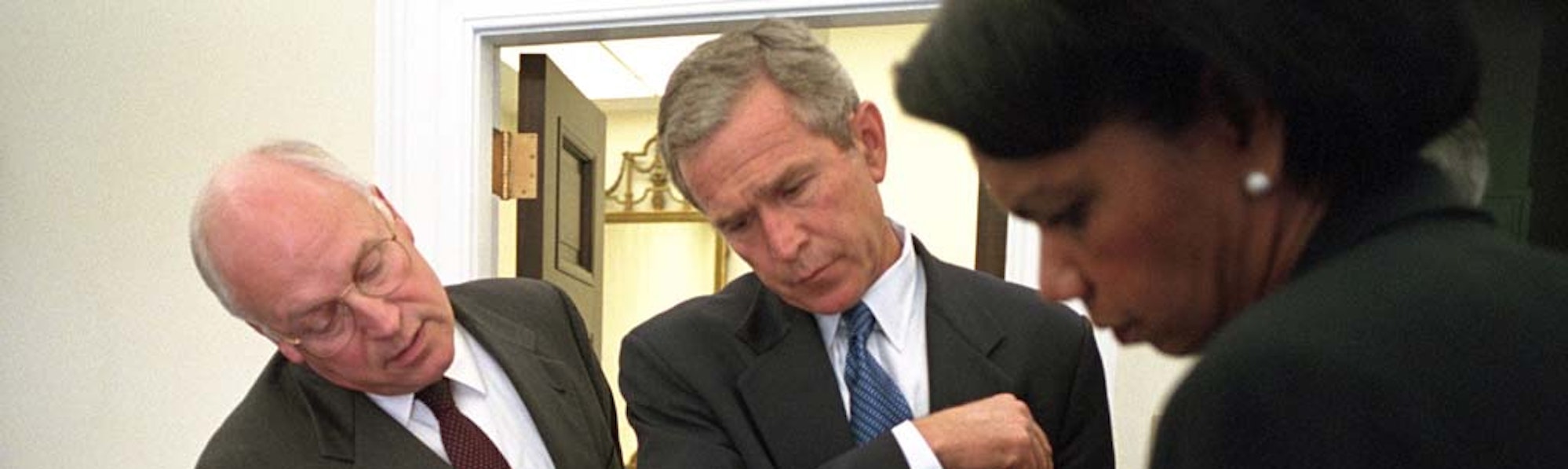

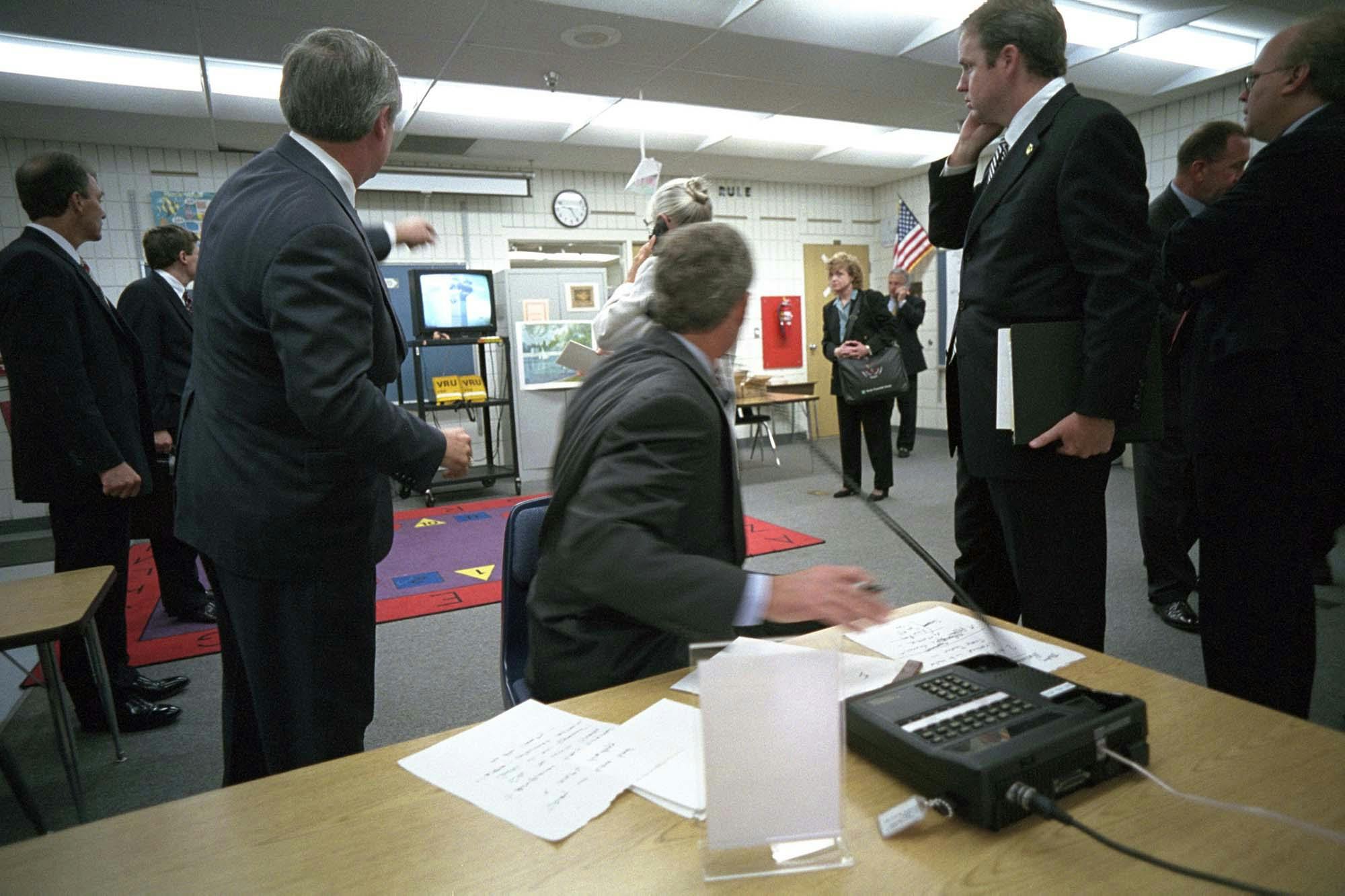

At 9:05, as the president read to students, Chief of Staff Andrew Card interrupted to whisper in his ear. “A second plane hit the second tower. America is under attack.” The president remained calm to avoid frightening the children. Within minutes, he and his team moved to a different classroom, with a phone and a television. He called Vice President Dick Cheney at the White House, New York Governor George Pataki, and FBI Director Robert Mueller. At 9:25, according to the wall clock in the classroom photo, the president saw a replay of the second plane hitting the south tower. This had happened about 20 minutes earlier, while the president was with the students, so he may have been seeing the shocking footage for the first time. Soon the president and his staff drove to the airport and boarded Air Force One. He asked the Secret Service to make sure his family was safe. His wife, Laura, was at the White House. His daughters were at universities in Connecticut and Texas.

Over the next hour, events moved at dizzying speed. Vice President Cheney was evacuated to a secure bunker beneath the White House. A third plane slammed into the Pentagon. The White House and Capitol were evacuated. Passengers and crew on a fourth hijacked plane learned of the other attacks and charged their captors to seize control of the aircraft. That plane crashed in Pennsylvania without reaching its target, later thought to be the US Capitol or the White House. In New York City, the two damaged towers of the World Trade Center collapsed to the ground. The attacks were over, but neither federal officials nor the American public knew this.

After Air Force One left Sarasota, flying to Washington, DC, was deemed too risky. The plane was diverted to secure military facilities, first in Louisiana and then in Nebraska. At the president’s insistence, he then flew to DC. He was back at the White House that evening, having had meetings and phone calls with his team all day, gathering information and discussing strategy. From the start, he labeled the attacks terrorism and vowed to retaliate. “We’re at war,” he said to Vice President Cheney soon after the third plane hit the Pentagon. Within hours, CIA director George Tenet presented evidence pointing to Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda as the organizers of the attacks.

At 8:30 p.m. on 9/11, the president addressed the nation and called the attacks “evil, despicable acts of terror.” He thanked Congress and world leaders for their support and spoke of fighting back. “America has stood down enemies before, and we will do so this time.”

The next morning, September 12, the president met with the National Security Council, which included his closest advisers: Vice President Dick Cheney, Secretary of State Colin Powell, National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. Questions and ideas flowed, and sometimes conflicted. Should the US focus on bin Laden? Attack al Qaeda? The Taliban? On the suspicion that Iraq was involved, should the US target Iraq? And how could the United States respond most quickly? Unmanned missile attacks? Bombs dropped by piloted aircraft? Commandos on the ground?

The president is the nation’s commander in chief during wartime. But for any military action, the president requires formal authorization from Congress. During the hours of September 12, a suggestion for a formal declaration of war was rejected by the White House. Instead, the president and members of Congress agreed to work on an Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF). This is the legal instrument that has authorized many military actions throughout the nation’s history, including all wars since World War II.

The White House drafted the first version of the AUMF. Members of Congress from both houses and both parties believed the language gave the president too much power, reminding many of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that authorized the Vietnam War. Congress ultimately produced the final version. The language, still broad, authorized the president to use military force against the masterminds of the 9/11 attacks or those who provided them with safe harbor. The AUMF was passed by Congress on September 14. The Senate vote was unanimously in favor. In the House of Representatives, Representative Barbara Lee was the only vote against. The president signed the bill on September 18, 2001.

The American people approved of a military response. As Congress was redrafting and voting on the AUMF, a poll showed strong public support for retaliation. President Bush’s approval rating climbed to 84 percent, more than 30 points higher than his score the previous month.

The war in Afghanistan began on October 7, 2001. A broad coalition of 42 countries joined the US effort, which went on year after year. Osama bin Laden was killed by US Navy Seals on May 1, 2011, during the administration of President Barack H. Obama. But al Qaeda survived and spun off other terrorist organizations in the Middle East and Africa, including al-Shabaab and Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).

Under the authority of the 2001 AUMF, the war in Afghanistan continued through the presidencies of George W. Bush, Barack H. Obama, and Donald J. Trump. The pursuit of terrorist groups, including al Qaeda and its spin-offs, spread into the Middle East and Africa. Under President Joseph R. Biden, the Afghanistan war was declared over, and US forces were withdrawn in August 2021, shortly before the 20th anniversary of 9/11. Within days, the Taliban had retaken control of Afghanistan.

Efforts to repeal the 2001 AUMF have been underway for years, but it continues to provide legal authority for US missions against terrorist organizations descended from al Qaeda, especially ISIL in Syria and Iraq.

- Air Force One.

The name of any plane that is equipped to transport the president.

- al Qaeda.

A militant Islamist organization founded in the late 1980s by Osama Bin Laden. Al Qaeda means “the base.”

- al-Shabaab.

An insurgent Islamist group, formed in the early 2000s, that has been working to establish an Islamic state in Somalia. Al-Shabaab means “the youth.”

- bunker.

A fortified location where people are safe from attack.

- Chief of Staff.

The person selected by the president to oversee the Executive Branch and work to further the president’s agenda.

- CIA.

Central Intelligence Agency, responsible for collecting information abroad that relates to US security.

- FBI.

Federal Bureau of Investigation, the agency that investigates crimes that violate national laws or threaten US security.

- hijacked.

Taken control of illegally.

- Islamic.

Related to Islam, the faith of Muslims.

- Levant.

A term from the French language, referring to the countries of Cyprus, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey.

- National Security Council.

A group of people who advise the president on national security and foreign policy decisions.

- Osama bin Laden.

The founder and leader of al Qaeda.

- Taliban.

A movement of fundamentalist Muslims that set up an Islamic state in Afghanistan in 1996. The Taliban was overthrown when the United States invaded after 9/11. It returned to power after the 2021 withdrawal of US troops.

How do you think the president’s personal experiences on 9/11 affected his attitudes about going to war?

What leadership style do you see in President George W. Bush after 9/11? How did this style affect his choices?

Compare the president’s reaction and thinking to Barbara Lee’s. Why do you think they were different?

Was the United States justified in fighting the war in Afghanistan?

At Osama bin Laden’s direction, al Qaeda attacked the World Trade Center in 1993. Research this event and its aftermath. Why do you think 9/11 came as such a shock to many Americans?

Compare President Bush’s response to 9/11 to President Truman’s handling of the threat of communism (Presidential Leadership). How did Truman’s decision in 1947 lead to the 2001 AUMF?

Life Story: Barbara Lee

The story of the only member of Congress to vote against the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Representative Barbara Lee was on Capitol Hill for a meeting. She called her office and learned that a plane had hit one of the World Trade Center towers in New York City. Soon she heard people screaming, “Evacuate the building!” She took off her shoes, ran outside, and saw smoke in the distance: the Pentagon had been hit.

Throughout the US government, determination to respond to the attacks came quickly. President George W. Bush consulted with congressional leaders. Both the White House and Congress wanted to show a unified America, with no party divisions. They decided on a joint resolution, issued by both the House of Representatives and the Senate, authorizing the use of force against those who had organized the attacks. In discussions, Barbara Lee and others urged restraint. She had grown up in a military family and was not a pacifist. She believed the people behind 9/11 should be held accountable. But she did not want the United States to head impulsively to war. She was trained in psychology and thought it unwise to make major decisions at highly emotional times.

Barbara Lee wanted serious, careful congressional debate. She worried about repeating the mistakes of the Vietnam War, which began when Congress approved the Tonkin Gulf Resolution and gave President Lyndon Johnson expansive war powers. When that war continued for years without clear victory, many in Congress felt that the president had been given too much power and that Congress had failed to do its job. In 1973, Congress passed the War Powers Act to reassert the war-making role of Congress. But in the decades years since, the War Powers Act had often been ignored and presidential power had grown.

Now, here was 9/11, the first direct attack on the US mainland since the British invaded during the War of 1812. Terrifying images played on television, thousands were dead, and no one knew what was coming next. Lee understood the urge to fight back hard, but she urged caution.

Some members of Congress suggested that Congress formally declare war, as it had in World War II. But the White House rejected this idea. Instead, on September 12, the Bush administration wrote and sent to Congress a draft of an Authorization for Use of Military Force, called an AUMF. Many in Congress were taken aback by how much war power it granted the president and how broadly it defined the enemy. Declared wars are typically fought against specific nations, with specific goals. This draft AUMF allowed the use of military action against “organizations or persons.” Rep. Lee called it unprecedented. Congress asked the administration to alter the language. Lee found the new, final draft essentially unchanged, but it became the final wording.

On September 14, 2001, President Bush, along with former presidents and current and former members of Congress and government officials, attended the memorial service in Washington for the lives lost and the country’s shattered sense of safety. Barbara Lee was among the mourners. When the service ended, members of Congress returned to Capitol Hill and began a five-hour debate on the AUMF. It was just three days after the attacks, and emotions were running high. Congress members stood to make their points. Some were more than ready to strike back. Others voiced concerns but wanted to show a united front.

Barbara Lee stood to make her statement. “I could barely speak,” she recalled later. “I was teary and feeling awful.” Be cautious, she advised. Let’s think before we act. She reminded her colleagues of the mistakes of Vietnam. She repeated a phrase she had heard at the memorial service: “Let us not become the evil that we deplore.”

Then it was time to vote on the AUMF, which Lee called the moment of truth. The members entered their votes electronically, and the results appeared as lights on a board, green for yes and red for no. “The board was full of green lights. There was only one red one. I had no idea I would be the only one.”

A group of fellow Democrats encouraged her to change her vote. Some wanted to show a unanimous US response. Some worried about Lee’s safety—with good reason. Over the next days, she received hate mail and death threats. The Capitol Police said she needed protection and accompanied her everywhere.

In 2002, another AUMF was introduced in Congress. This one permitted the use of force against Iraq, which many believed had stockpiled weapons of mass destruction. Barbara Lee introduced an amendment that called for relying on diplomacy and surveillance by United Nations weapons inspectors, rather than a military response. She predicted that the Iraq AUMF would “come back to haunt us.” Her amendment was voted down, and the 2002 AUMF passed, although with a substantial number of no votes.

Over the next two decades in the House of Representatives, Barbara Lee has focused on numerous issues, especially related to HIV/AIDS. And during this time, the two AUMFs have remained in place. She has regularly introduced bills to sunset the 2001 AUMF—which means to let it expire at the end of a specified period—and to repeal the 2002 AUMF. Despite her efforts, some experts believe it will be difficult to undo the 2001 AUMF, which provides the authority for ongoing antiterrorism campaigns.

- Capitol Hill

The part of Washington, DC, where the Capitol building is. Congress works in the Capitol building.

- joint resolution

A legislative measure that requires the approval of both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

- HIV/AIDS

HIV is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system. AIDS is the most serious form of the disease caused by the virus.

- Tonkin Gulf Resolution

A resolution passed by Congress in August 1964 after allegations of an attack, later proven untrue, on US ships off the coast of Vietnam. The resolution became President Lyndon Johnson’s main authorization for the Vietnam War.

- War Powers Act

A 1973 law meant to limit the president’s power to begin an armed conflict without the consent of Congress.

Why did Barbara Lee vote no on the 2001 AUMF?

What did she think Congress should have done in the days and weeks after 9/11?

What link did she see between the 2001 AUMF and the Vietnam War? Why did it worry her?

At the National Prayer Service held on September 14, 2001, Barbara Lee heard a member of the clergy warn against becoming “the evil that we deplore.” It informed her decision to vote no on the 2001 AUMF. The entire service is on C-SPAN here.

Research the current status of the 2001 AUMF. Begin with an online search for “repeal 2001 AUMF” or “repeal 107-40.” Bills in progress can be followed at congress.gov and govtrack.us.

Source Notes

Sources consulted for this unit were:

- Abramowitz, David. "The President, the Congress, and Use of Force: Legal and Political Considerations in Authorizing Use of Force against International Terrorism." Harvard International Law Journal 43, no. 1 (Winter 2002): 71-82.

- The Council on Foreign Relations. “The U.S. War in Afghanistan, 1999-2021.” https://www.cfr.org/timeline/us-war-afghanistan.

- Elsea, Jennifer K., and Matthew C. Weed. “Declarations of War and Authorizations for the Use of Military Force: Historical Background and Legal Implications.” Congressional Research Service, April 18, 2014, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/RL31133.pdf.

- Grimmet, Richard F. “Authorization for Use of Military Force in Response to the 9/11 Attacks (P.L. 107-40): Legislative History.” Congressional Research Service, January 16, 2007, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/RS22357.pdf.

- Lee, Barbara. Renegade for Peace and Justice: A Memoir of Political and Personal Courage. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2008.

- The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. “The 9/11 Commission Report.” July 22, 2004, https://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report_Exec.htm.

- 9/11 Memorial. “September 11 Attack Timeline.” https://timeline.911memorial.org/#Timeline/2.

- US Department of State. “Report on the Legal and Policy Frameworks Guiding the United States’ Use of Military Force and Related National Security Operations.” October, 2019, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Report-to-Congress-on-legal-and-policy-frameworks-guiding-use-of-military-force-.pdf.

- Weed, Matthew. “Presidential References to the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force in Publicly Available Executive Actions and Reports to Congress.” Congressional Research Service, February 16, 2018, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/pres-aumf.pdf.

- The White House. “Report on the Legal and Policy Frameworks Guiding the United States’ Use of Military Force and Related National Security Operations.” December, 2016. https://www.justsecurity.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/framework.Report_Final.pdf.

- Woodward, Bob. Bush at War. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002.

Credits

Writer:

Marjorie Waters

Project Director:

Mia Nagawiecki

Leslie Hayes

Project Manager:

Lee Boomer

Project Historian:

Meena Bose

Special Thanks:

Carol Barkin, Copy Editor

Use All 5, Website Developer

Dayna Bealy, Rights Clearance Specialist